LAO Contact

April 26, 2021

The 2021-22 Budget

The Governor’s Proposition 2 Proposals

Introduction

Passed by voters in 2014, Proposition 2 changed budgeting practices concerning: (1) reserves and (2) debt payments. This post provides an overview of the Governor’s proposals related to Proposition 2. First, we provide some background on how the measure works. In the subsequent three sections, we summarize and comment on (1) the Governor’s overall Proposition 2 estimates and requirements, (2) the reserve proposals, and (3) the debt payment requirements.

How Proposition 2 Works

Key Provisions of Proposition 2 Calculation. Proposition 2 made two major constitutional changes to state budgeting. First, it created new rules for minimum annual deposits into the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA), the state’s rainy-day fund. Second, Proposition 2 created new requirements that the state spend a minimum amount each year, until 2030, to pay down specified debts.

As shown in Figure 1, Proposition 2 has two avenues for making reserve deposits and paying debt. First, it requires the state to set aside 1.5 percent of total General Fund revenues (we refer to this as the “base amount”). Second, it requires the state to put aside a portion of capital gains revenues that exceed a specified threshold (this is “excess capital gains”). The state combines these two amounts and then allocates half of the total to pay down debts and the other half to build the rainy-day reserve. (For reader clarity, Figure 1 makes some simplifications to the actual calculation.)

Figure 1

True Up Provisions. Under Proposition 2’s “true up” provisions, the state reevaluates the BSA estimate twice: once in each two subsequent budgets. Under these reevaluations, the state revises the BSA deposit up or down if capital gains taxes were higher or lower than the state’s prior estimates. Figure 1 shows a simplified example of a true up requirement. The state does not revisit its estimate of the base amount in the true up calculation. Debt payments also are not adjusted when new capital gains estimates are available later, which means that the revised estimate affects reserves but not debt payments. This means that initial overestimates of capital gains result in more debt payments, while underestimates of capital gains result in more reserve deposits. That is, for the same amount of eventual capital gains revenue, overestimating those revenues in advance will result in more debt payments than reserve deposits and vice versa.

Withdrawals Permitted in the Event of a Budget Emergency. The Legislature can suspend a BSA deposit or make a withdrawal from the mandatory share of the BSA if the Governor declares a budget emergency. The Governor may call a budget emergency in two cases: (1) if estimated resources in the current or upcoming fiscal year are insufficient to keep spending at the level of the highest of the prior three budgets, adjusted for inflation and population, or (2) in response to a natural or man-made disaster.

Required Infrastructure Spending After BSA Reaches Threshold Level. Under Proposition 2, the state must continue to deposit funds into the BSA until it reaches a threshold balance of 10 percent of General Fund tax revenue. Once the BSA reaches this threshold, required deposits that would bring the fund above 10 percent of General Fund taxes instead must be spent on infrastructure. (Once at the 10 percent threshold, the Legislature can continue to make optional deposits into the BSA at its discretion.)

Governor’s Budget Assumptions and Overall Requirements

Governor’s Estimates

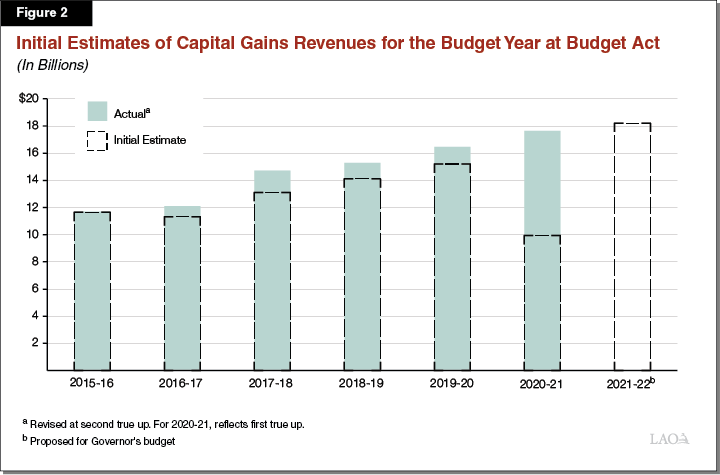

Capital Gains Revenue Assumptions. The administration makes the following capital gains revenue assumptions in the Governor’s budget: $16.5 billion in 2019‑20, $17.6 billion in 2020‑21, and $18.1 billion in 2021‑22. The amount projected for 2021‑22 is higher than what previous budgets have assumed for the budget year (see Figure 2). As the figure shows, recent budgets have tended to underestimate capital gains, meaning the estimates are below the actuals. When the state underestimates capital gains, the state must true up the BSA for the entire difference in the Proposition 2 requirement.

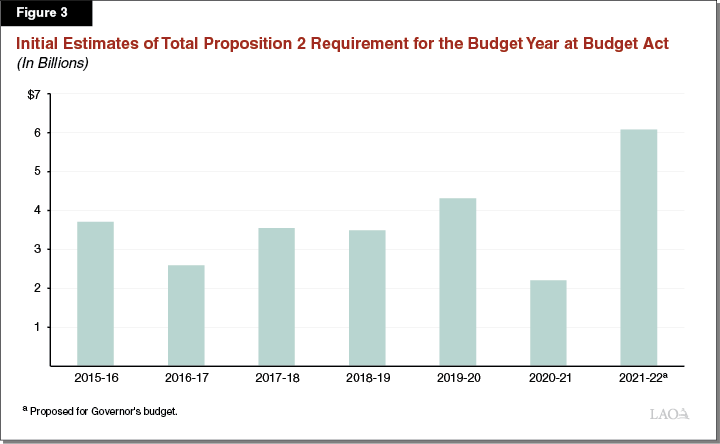

Total Proposition 2 Requirement of $6.1 Billion in 2021‑22. These capital gains assumptions result in above-average total Proposition 2 requirements for 2021‑22. Specifically, the state’s total requirement would be $6 billion in 2021‑22, split half between reserves and debt payments. As figure 3 shows, this total requirement is substantially above any other Proposition 2 requirement for the budget year.

LAO Comments

Capital Gains Revenues Are Uncertain. Capital gains depend heavily on movements in financial markets. This means that in order to project capital gains revenues for the budget year—to fulfill the Proposition 2 requirements—the state must estimate the level and growth of the stock market between July 2021 and June 2022. Such predictions are extremely difficult. In the past, our office has examined the historical pattern of financial markets to gauge the range of possible outcomes for capital gains revenue in the budget year and beyond. We discuss those findings in the context of the Governor’s estimates below.

Good Chance Capital Gains Revenues for 2021‑22 Could Exceed Projections, but Estimates Are Uncertain. Using our analysis of historical patterns, there is, in fact, a good chance that actual capital gains revenues could beat this projection. That said, there also is a real possibility of a stock market correction which would result in capital gains revenue well below projections. Specifically, under our estimates, 10 percent of historical scenarios are below the Department of Finance’s (DOF’s) forecast and 90 percent of scenarios are above DOF’s forecast for 2021‑22. That is, although the state has historically underestimated capital gains revenues, the data to date suggest the state is unlikely to do so with the Governor’s budget estimates. If actual capital gains are higher than anticipated at budget act, the state will have to true up reserves. If those capital gains do not materialize, the state will true down reserves. Debt payments would remain unchanged, however.

Revenue Estimates and Requirements Will Change in May. When the Governor releases revised budget estimates in May, the administration will change its assumptions regarding overall revenues and capital gains revenues in particular. This will mean that the Proposition 2 requirements also will change. Collections data to date have exceeded Governor’s budget estimates, suggesting the administration might increase its projections for 2021‑22.

Reserves

Background

When the Legislature passed the budget act in 2020, it anticipated the state faced a budget problem of over $50 billion. To help address the problem, last year’s budget suspended the otherwise required deposit for 2020‑21 and made a $7.8 billion withdrawal from the BSA, lowering the total balance to $8.3 billion. The withdrawal was made pursuant to the Governor’s disaster declaration in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) public health emergency and proclamation of a budget emergency on June 25, 2020. The budget included a withdrawal of $4.7 billion from the state’s mandatory BSA balance and $3.1 billion from the state’s optional BSA balances. The nearby box describes the BSA “optional balance” in more detail.

Optional Balance of the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA)

Legislature Has Made Two Optional Deposits Into the BSA. Since Proposition 2 (2014) was passed, the Legislature has elected to deposit additional amounts into the BSA above the constitutionally required minimums. In particular, the Legislature deposited an additional $2 billion into the BSA in 2016-17 and an additional $2.6 billion in 2018-19. However, a portion of these deposits ultimately were used to fund required true ups. So, as of the end of 2019-20, the total amount of the optional balance in the BSA was $3.1 billion. The remainder of the balance of the BSA is “mandatory,” meaning it is composed of deposits required under the constitution.

Optional Deposits Do Not Count Toward Threshold Balance. Under the state’s interpretation of Proposition 2, the constitutional rules restricting the use and withdrawal of BSA deposits are limited to the mandatory balance of the account. Under this interpretation, optional deposits into the BSA can be used by the Legislature at any time and do not count toward the 10 percent threshold level discussed earlier (which triggers an infrastructure spending requirement). This means that mandatory deposits must continue until their balance reaches the threshold level, but the overall balance of the BSA is not limited.

Governor’s Budget

Required BSA Deposits of $7.2 Billion. Under the administration’s revenue estimates, the total reserve level of the BSA would reach $15.6 billion by the end of 2021‑22. (For comparison, the BSA balance would have totaled $18 billion under 2020‑21 Governor’s Budget. This means the level would not quite reach the pre-COVID-19 total.) Across the budget window, the state would need to make required BSA deposits of $7.6 billion, which has three components:

$1 Billion True Up for 2019‑20. Under the administration’s revenue estimates, the state would need to make a true up deposit of $1 billion in 2019‑20. This is due to an increase in the capital gains revenue estimate in that year, from $14.5 billion (at 2019‑20 Budget Act) to $16.5 billion at Governor’s budget.

$3.2 Billion True Up for 2020‑21. Under the administration’s revenue estimates and constitutional interpretations, the state would need to make a true up deposit of $3.2 billion for 2020‑21. This is due to much higher than anticipated revenues, including capital gains, but also the administration’s interpretation regarding true up deposits on suspended deposits.

$3 Billion Deposit for 2021‑22. Under the administration’s revenue assumptions, the state would need to make an initial deposit of $3 billion for 2020‑21. This is largely the result of the administration’s estimate of capital gains revenues, as discussed earlier.

Proposes Reducing Optional Deposit Withdrawal. Under the administration’s estimates and proposals, the state still would make a $7.8 billion withdrawal from the BSA in 2020‑21. However, the administration proposes lowering the optional balance withdrawal from 2020‑21 from $3.1 billion to $1.3 billion. (This results in a corresponding increase in the mandatory withdrawal, from $4.7 billion to $6.5 billion.) Under the state’s interpretation of the withdrawal rules in the case of a disaster, the state could withdraw any amount from either the optional or mandatory balance in 2020‑21.

LAO Comments

True Up Requirement for 2020‑21 Could Be Higher at May Revision. As discussed earlier, capital gains revenues are highly uncertain. Even though the administration’s estimate for capital gains revenues in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22 are relatively high, there is a reasonable chance these estimates will be even higher at the May Revision. In fact, based only on January revenue collections, Proposition 2 reserve deposits for 2020‑21 would be higher by around $1.5 billion. That is because, overall, January collections from the state’s three largest taxes were $7.5 billion (42 percent) ahead of budget projections and, based on historical patterns, we anticipate that a substantial share of these revenues came from taxpayer realization of capital gains.

Reducing Optional Withdrawal Lowers Probability of Required Capital Outlay Spending in 2022‑23. When the mandatory portion of the BSA reaches 10 percent of General Fund revenues, the state will be required to spend the funds that would have been deposited into the BSA on infrastructure. By reducing the optional withdrawal from the BSA, the Governor proposes increasing the optional balance, and reducing the mandatory balance, of the BSA. As a result, reaching the 10 percent threshold for mandatory balances will require more deposits over time. This would delay spending on infrastructure, but could increase the overall level of state reserves.

Legislature Could Set Optional Withdrawal at Any Level. Regarding the mix of optional versus mandatory withdrawals from the BSA, the Legislature could make a different choice. To increase the chances of additional infrastructure spending sooner (and reduce the balance of the BSA), the Legislature could maintain the optional withdrawal amount from the 2020‑21 Budget Act. To delay the chances of additional infrastructure spending (and increase the balance of the BSA), the Legislature could further lower the optional withdrawal. The Legislature can set the optional withdrawal at any level between zero and $3.1 billion.

Debt Payments

Background

Proposition2 Payments Must Be Dedicated to Certain Eligible Uses. Proposition 2 requires the state to spend a minimum amount each year to pay down specified debts through 2029‑30. When Proposition 2 was passed by the voters, there were two major categories of liabilities eligible for repayment using these monies: certain budgetary liabilities and retirement liabilities. Since then, the state has repaid all of the eligible budgetary debts, meaning the remaining eligible uses of Proposition 2 are related to unfunded liabilities for pensions and retiree health benefits, as shown in Figure 4. (We provide additional background and detail on the remaining eligible uses of Proposition 2 here.)

Figure 4

Outstanding State‑Only Eligible Uses of Proposition 2

(In Billions)

|

Debt or Liability |

|

|

Retiree health |

$91.9 |

|

State and CSU employee pensions |

61.4 |

|

Teachers’ pensionsa |

33.1 |

|

Judges’ pensions |

3.2 |

|

Pooled Money Investment Account loanb |

1.8 |

|

aState’s share of the unfunded liability. bGeneral Fund’s share of the remaining payments. Total outstanding repayments owed are $4.6 billion, including interest. |

|

Governor’s Budget

Policies in 2020‑21 Grew Retirement Liabilities. Certain policies enacted in 2020‑21 to generate General Fund savings during the COVID-19 emergency directly contributed to growth in state retirement liabilities that will be reflected in future actuarial valuations. In particular, these relate to:

-

Pensions. The state and employees each contribute to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) a specified percentage of pay to fund pension benefits. During 2020‑21, state employees are subject to a Personal Leave Program (PLP), which reduces state employee pay in exchange for time off. During PLP, state and employee contributions to CalPERS are based on the reduced pay levels; however, the benefits earned by state employees are based on their full salary, systematically creating an unfunded liability.

-

Retiree Health. The state and employees each contribute about one-half of normal cost—expressed as a percentage of pay—to prefund retiree health benefits. Labor agreements between the state and state employees suspended employee contributions to prefund retiree health benefits for the duration of PLP. The suspension of employee contributions, combined with lower state contributions being made because of lower salary levels during PLP, result in growth in retiree health unfunded liabilities (we provide a more detailed explanation of this in the “Overarching LAO Comments and Recommendations” section of our analysis of current labor agreements).

-

California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS). The state, school employers, and teachers each contribute a percentage of pay to fund teachers’ pension benefits. CalSTRS’ board holds limited authority to adjust these contribution rates each year, pursuant to the provisions of the CalSTRS funding plan (Chapter 47 of 2014 [AB 1469, Bonta]). In 2020‑21, as a way to reduce state costs, the budget suspended the board’s ability to increase the state’s rate, holding the state’s rate flat for one year. This budget action resulted in (1) General Fund savings of $169 million in 2020‑21 and (2) beginning in 2021‑22, the state’s contribution rate starting at a level that is lower by 0.5 percentage points relative to what it would have been in the absence of this action. The lower state contribution rate increases state unfunded liabilities over the long term. (The administration has proposed a one-time additional payment to CalSTRS in 2021‑22 using General Fund dollars outside of the Proposition 2 requirement, which would offset the 2020‑21 rate suspension for one year, but not on an ongoing basis. We discuss options for the Legislature to take additional steps to address this unfunded liability in our report, Strengthening the CalSTRS Funding Plan.)

Governor Proposes Accelerating Pay Off of Retirement Liabilities. The Governor proposes that the state use Proposition 2 funds in 2021‑22 to address the creation of new unfunded liabilities generated in 2020‑21 and to accelerate pay off of all three of the state’s retirement liabilities. Specifically, the Governor proposes one-time payments of: (1) $1.5 billion as a supplemental pension payment to CalPERS state pension plans (apportioned across the plans based on the annual General Fund contributions to each plan), (2) $926 million toward the state’s retiree health unfunded liabilities ($616 million of this would be intended to make up for employee contributions that were suspended during PLP in 2020‑21), and (3) $410 million as a supplemental pension payment to CalSTRS to help pay down the state’s share of unfunded liabilities.

LAO Comments

Proposed Use of Proposition 2 Funds Consistent With Past LAO Recommendations. In March 2020 (see page 8 of our analysis), we recommended that Proposition 2 funds be used to keep existing funding plans for CalSTRS and retiree health benefits on track to pay off the unfunded liabilities by the mid-2040s. The administration’s proposed 2021‑22 Proposition 2 payments to CalSTRS and retiree health benefits are consistent with this past recommendation. In a 2019 analysis, we noted that additional capacity in Proposition 2 could be directed toward CalPERS because that would achieve the highest chances of state savings over the next few years. The proposed payment to CalPERS also is consistent with that consideration.

Pension Payments Could Better Maximize General Fund Benefit. In 2019‑20, the Governor proposed a similar supplemental payment to CalPERS using a similar methodology—use General Fund resources, but apportion the payment across the plans based on the annual General Fund contributions to each plan. In a 2019 analysis of the proposal, we noted that there are other alternative options that would either provide more General Fund benefit or provide benefit to some special funds that would otherwise be excluded (for example, the Motor Vehicle Account). That finding also applies to the Governor’s current proposal for a CalPERS supplemental payment.

Conclusion

In May, the administration will release its updated revenue assumptions and those assumptions will imply different Proposition 2 requirements. As such, decisions about Proposition 2 are intrinsically tied to the overall budget condition and must be made as part of the final budget negotiations. Although the State Constitution prescribes set formulas with the requirements of Proposition 2, the assumptions that underpin those requirements are often a matter of legislative discretion. As such, we suggest the Legislature consider its preferences on some of the alternatives we have listed above before the May Revision. For example, would it prefer the state be more or less likely to have an infrastructure spending requirement in 2022‑23? Among a reasonable range of options, would the Legislature prefer to include a higher capital gains revenue assumption in the budget—making a true down of BSA reserves more likely—or vice versa? The answers to these and other questions should ultimately guide policymakers as they choose the appropriate assumptions and choices about the measure.