LAO Contact

February 11, 2022

The 2022-23 Budget

Analysis of Major CCC Proposals

- Introduction

- Overview

- Apportionments Increase

- Enrollment

- Student Centered Funding Formula

- Part‑Time Faculty Health Insurance

- Facility Maintenance

Summary

Brief Covers Major Proposals for California Community Colleges (CCC). This brief focuses on the Governor’s proposals related to CCC apportionments, enrollment, modifications to the Student Centered Funding Formula (SCFF), part‑time faculty health insurance, and deferred maintenance. Proposals in these areas account for three‑quarters of the Governor’s ongoing augmentations and about half of his one‑time spending for community colleges.

Community Colleges Facing Heightened Challenges. In 2022‑23, districts are facing greater pressure to increase employees’ salaries given high inflation; cover scheduled increases in their pension contributions, partly due to expiring state pension relief; and adjust to the expiration of federal relief funds. Consistent with nationwide trends, CCC as a system also has experienced significant enrollment declines since the beginning of the pandemic. Though preliminary data for 2021‑22 suggest some districts may be starting to recover lost enrollment, the current favorable job market and unknown trajectory of the pandemic make predicting when enrollments will return difficult. In addition, a number of districts face a “fiscal cliff” in 2025‑26 when a key hold harmless provision related to SCFF is scheduled to expire.

Opportunities to Build on Governor’s Proposals. To address districts’ fiscal challenges, the Legislature may wish to provide a greater cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) for apportionments than the $409 million (5.33 percent) proposed in the Governor’s budget. Also, to the extent the Legislature is concerned both with districts’ enrollment declines and their ability to cover continued COVID‑19‑related costs in 2022‑23, it could repurpose the Governor’s proposed $150 million one‑time funding for student outreach into a more flexible block grant. Districts could be allowed to use block grant funds for student outreach and recruitment, student mental health services, or COVID‑19 mitigation, among other potential purposes. We also recommend the Legislature consider modifying the Governor’s SCFF hold harmless proposal by beginning to explore the possibility of increasing base funding for SCFF (beyond annual COLAs). Higher base SCFF funding would have the effect of shifting districts out of hold harmless more quickly while also helping them with rising core operating costs and declining enrollment. If the Legislature wanted to start moving toward those higher rates in 2022‑23, it potentially could redirect ongoing funds from other proposals (including the Part‑Time Faculty Health Insurance Program).

Introduction

This brief is organized around the Governor’s major 2022‑23 budget proposals for the California Community Colleges (CCC). The first section of the brief provides an overview of the Governor’s CCC budget package. The remaining five sections of the brief focus on the apportionments funding increase, enrollment, the Student Centered Funding Formula (SCFF), part‑time faculty health insurance, and deferred maintenance, respectively. Proposals related to these issues account for three‑quarters of the Governor’s ongoing augmentations and about half of his one‑time spending. We anticipate covering other CCC proposals in subsequent products.

Overview

Total CCC Funding Is $17.3 Billion Under Governor’s Budget. Of CCC funding, $11.6 billion comes from Proposition 98 funds. As Figure 1 shows, Proposition 98 support for CCC in 2022‑23 increases by $518 million (4.7 percent) over the revised 2021‑22 level. In addition to Proposition 98 General Fund, the state provides CCC with a total of $658 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund for certain purposes. Most notably, non‑Proposition 98 funds cover debt service on state general obligation bonds for CCC facilities, a portion of CCC faculty retirement costs, and operations at the Chancellor’s Office. Much of CCC’s remaining funding comes from student enrollment fees, other student fees (such as nonresident tuition, parking fees, and health services fees), and various local sources (such as revenue from facility rentals and community service programs). In 2020‑21 and 2021‑22, community colleges also received a significant amount of federal relief funds. These federal funds must be spent or encumbered by May 2022, as discussed in the nearby box.

Figure 1

California Community Colleges Rely Heavily on Proposition 98 Funding

(Dollars in Millions Except Funding Per Student)

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

Change From 2021‑22 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Proposition 98 |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$7,392 |

$7,528 |

$7,827 |

$299 |

4.0% |

|

Local property tax |

3,374 |

3,546 |

3,766 |

220 |

6.2 |

|

Subtotals |

($10,766) |

($11,075) |

($11,593) |

($518) |

(4.7%) |

|

Other State |

|||||

|

Other General Fund |

$619 |

$644 |

$658 |

$13 |

2.1% |

|

Lottery |

275 |

273 |

272 |

—a |

‑0.1 |

|

Special funds |

44 |

94 |

94 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($937) |

($1,011) |

($1,024) |

($13) |

(1.3%) |

|

Other Local |

|||||

|

Enrollment fees |

$446 |

$446 |

$448 |

$1 |

0.3% |

|

Other local revenueb |

3,833 |

3,860 |

3,888 |

28 |

0.7 |

|

Subtotals |

($4,279) |

($4,306) |

($4,336) |

($30) |

(0.7%) |

|

Federal |

|||||

|

Federal stimulus fundsc |

$1,431 |

$2,648 |

— |

‑$2,648 |

— |

|

Other federal funds |

365 |

365 |

$365 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($1,797) |

($3,014) |

($365) |

‑($2,648) |

‑(87.9%) |

|

Totals |

$17,779 |

$19,405 |

$17,318 |

‑$2,087 |

‑10.8% |

|

FTE studentsd |

1,097,850 |

1,107,543 |

1,101,510 |

‑6,033 |

‑0.5%e |

|

Proposition 98 funding per FTE studentd |

$9,807 |

$9,999 |

$10,524 |

$525 |

5.3% |

|

aDifference of less than $500,000. bPrimarily consists of revenue from student fees (other than enrollment fees), sales and services, and grants and contracts, as well as local debt‑service payments. cConsists of federal relief funds provided directly to colleges as well as allocated through state budget decisions. dReflects budgeted FTE students. Though final student counts are not available for any of the periods shown, preliminary data indicate CCC enrollment dropped in 2020‑21, with a likely further drop in 2021‑22. Districts, however, have not had their enrollment funding reduced due to certain hold harmless provisions that have insulated their budgets from drops occurring during the pandemic. eReflects the net change after accounting for the proposed 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth together with all other enrollment adjustments. |

|||||

|

FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

Federal Relief Funds

Community Colleges Received Considerable Federal Relief Funding. Community colleges received a total of $4.7 billion over three rounds of federal relief funding in response to COVID‑19. (Our Federal Relief Funding for Higher Education table provides more detail on California Community College relief funds.) Collectively, colleges are required to spend at least $2 billion of their relief funds for direct student aid. The rest can be used for institutional operations. Colleges have used institutional funds for a variety of purposes, including to undertake screening and other COVID‑19 mitigation efforts, cover higher technology costs related to remote operations, purchase laptops for students, and backfill lost revenue from parking and other auxiliary college programs.

Deadline for Colleges to Spend Federal Relief Funds Is Approaching. Colleges must spend or encumber federal relief funds by May 2022, unless they apply for and receive an extension from the federal government. Though systemwide data on college expenditures is not readily available, a review of a subset of colleges suggests more than half of their student aid funds and just under half of their institutional funds had been spent as of December 31, 2021. Comprehensive information also is not yet available on the colleges that requested and received extensions. When we surveyed districts in fall 2021, several districts indicated they had requested extensions, but those requests had not been granted.

Governor’s Budget Contains Many CCC Proposition 98 Spending Proposals. The Governor has 10 ongoing and 11 one‑time CCC spending proposals. As Figure 2 shows, the Governor’s ongoing spending proposals total $843 million, whereas his one‑time initiatives total $983 million. His largest ongoing spending proposals are a 5.33 percent cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) for apportionments and a major expansion of the Part‑Time Faculty Health Insurance Program. His largest one‑time proposals are for facility maintenance and student enrollment and retention strategies. Spending on facility maintenance ($388 million) would be excluded from the state appropriations limit (SAL) under the Governor’s budget. (In our report, The 2022‑23 Budget: Initial Comments on the State Appropriations Limit Proposal, we cover SAL issues in more detail.)

Figure 2

Governor Has Many Proposition 98

Spending Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Ongoing Proposals |

|

|

COLA for apportionments (5.33 percent) |

$409 |

|

Part‑Time Faculty Health Insurance Program |

200 |

|

Student Success Completion Grants (caseload adjustment) |

100 |

|

COLA for select categorical programs (5.33 percent)a |

53 |

|

Technology security |

25 |

|

Enrollment growth (0.5 percent) |

25 |

|

Equal Employment Opportunity program |

10 |

|

Financial aid administration |

10 |

|

NextUp foster youth program |

10 |

|

A2MEND program |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

($843) |

|

One‑Time Initiatives |

|

|

Facilities maintenance and instructional equipment |

$388 |

|

Student enrollment and retention strategies |

150 |

|

Health care pathways for English learners |

130 |

|

Common course numbering implementation |

105 |

|

Technology security |

75 |

|

Transfer reform implementation |

65 |

|

Intersegmental curricular pathways software |

25 |

|

STEM, education, and health care pathways grant program |

20 |

|

Emergency financial assistance for AB 540 students |

20 |

|

Teacher Credentialing Partnership Pilot |

5 |

|

Umoja program study |

—b |

|

Subtotal |

($983) |

|

Total |

$1,826 |

|

aApplies to the Adult Education Program, apprenticeship programs, CalWORKs student services, campus child care support, Disabled Students Programs and Services, Extended Opportunity Programs and Services, and mandates block grant. bReflects $179,000. |

|

|

COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment; A2MEND = African American Male Education Network and Development; and STEM = science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. |

|

No Proposals for Addressing Unfunded Retirement Liabilities or Providing Pension Relief. In recent years, the Governor has had various budget proposals relating to education pension funding. These proposals have included making supplemental payments toward pension systems’ unfunded liabilities as well as giving community college districts immediate pension relief by subsidizing their rates in 2019‑20, 2020‑21, and 2021‑22. Though community colleges’ employer pension contribution rates are expected to rise notably in 2022‑23, the Governor does not have any such proposals this year.

Proposes No Change to Enrollment Fee. State law currently sets the CCC enrollment fee at $46 per unit (or $1,380 for a full‑time student taking 30 semester units per year). The Governor proposes no increase in the fee, which has remained flat since summer 2012.

Funds 18 Capital Projects. The Governor proposes to provide $373 million in state general obligation bond funding to continue 18 previously authorized community college projects. Of these projects, 17 are for the construction phase and 1 is for the working drawings phase. All bond funds would come from Proposition 51 (2016). A list of these projects and their associated costs is available on our EdBudget website.

Governor Announces a “Roadmap” for CCC. The roadmap for CCC is somewhat different than the compacts for the California State University (CSU) and the University of California (UC) in that it does not specify in advance what will be the size of future base funding increases. Instead, the Governor indicates that community colleges’ base increases would depend upon available Proposition 98 funds in future years. The roadmap is similar to the university compacts, however, in setting forth certain expectations to be achieved by the colleges over a five‑year period. The 15 expectations for the community colleges include increasing student graduation and transfer rates, closing equity gaps, establishing a common intersegmental learning management system and admission platform, and enhancing K‑14 as well as workforce pathways. We describe and assess the Governor’s roadmap with CCC, as well as his multiyear agreements with CSU and UC, in our publication, The 2022‑23 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Higher Education Budget Proposals.

Apportionments Increase

In this section, we provide background on community college apportionments, describe the Governor’s proposal to increase apportionments for inflation, assess the proposal, and provide a recommendation.

Background

Most CCC Proposition 98 Funding Is Provided Through Apportionments. Every local community college district receives apportionment funding, which is available for covering core operating costs. Although the state is not statutorily required to provide community colleges a COLA on their apportionment funding (as it is for K‑12 schools), the state has a longstanding practice of providing one when there are sufficient Proposition 98 resources. The COLA rate is based on a price index published by the federal government that reflects changes in the cost of goods and services purchased by state and local governments across the country.

Compensation Is Largest District Operating Cost. On average, community college districts spend about 85 percent of their core operating budget on salary and benefit costs. While the exact split varies from district to district, salaries and wages can account for up to about 70 percent of total compensation costs. District pension contributions typically account for another 10 percent to 15 percent of total compensation costs. Health care costs vary among districts, but costs for active employees commonly account for roughly 10 percent of compensation costs, with retiree health care costs typically comprising less than 5 percent. Additionally, districts must pay various other compensation‑related costs, including workers’ compensation and unemployment insurance, which collectively tend to account for about 5 percent of total costs. Districts’ other core operating costs include utilities, insurance, software licenses, equipment, and supplies. On average, about 15 percent of districts’ operating budget is for these noncompensation‑related expenses.

Proposal

Governor Funds Apportionment COLA. The Governor’s largest proposed ongoing augmentation for the community colleges is $409 million to cover a 5.33 percent COLA for apportionments. This is the same percentage as the Governor proposes for the K‑12 Local Control Funding Formula. (It is also the same COLA rate the Governor proposes for certain CCC categorical programs, including the mandate block grant, Disabled Students Programs and Services, and Extended Opportunity Programs and Services.)

Assessment

COLA Likely to Be Higher in May. The federal government released additional data used to calculate the apportionment COLA on January 27. Using this additional data, our office estimates the COLA for 2022‑23 will be closer to 6.17 percent (about 0.8 percentage points higher than the Governor’s January estimate). Covering this higher COLA rate for community college apportionments would cost about $475 million, or about $65 million more than included in the Governor’s budget.

Districts Are Facing a Couple of Notable Compensation‑Related Cost Pressures in 2022‑23. Augmenting apportionment funding can help community colleges accommodate operating cost increases. One notable cost pressure in 2022‑23 is salary pressure. With inflation higher than it has been in decades, districts are likely to feel pressure to provide salary increases. (If the total CCC salary pool were increased 3 percent to 6 percent, associated costs would range from roughly $200 million to $400 million.) A second notable cost pressure relates to districts’ pension costs. Updated estimates suggest that community college pension costs will increase by a total of more than $120 million in 2022‑23, which represents about 30 percent of the COLA funding proposed by the Governor. (Like the other education segments, community college districts also expect to see higher costs in 2022‑23 for insurance, equipment, and utilities, though these cost increases could be partly offset by costs potentially remaining lower than normal in other areas, such as travel.)

Depending on Enrollment Demand, Districts Could Realize Some Workload‑Related Savings. As a result of declining enrollment since the onset of the pandemic, districts generally have been offering fewer course sections. On a systemwide basis, districts offered 45,000 fewer course sections in 2020‑21 than in 2019‑20, which likely resulted in tens of millions of dollars in savings from needing to pay fewer part‑time faculty. (When districts reduce course sections, they typically reduce their use of part‑time faculty, who are considered temporary employees, compared to full‑time faculty, who are considered permanent employees.) To the extent districts continue to experience soft enrollment demand in 2022‑23, they potentially could continue to realize lower costs due to employing fewer part‑time faculty. (On net, however, colleges are still expected to see notable upward pressure on their total compensation costs in 2022‑23.)

Districts Face Cost Pressures Stemming From Expiration of Federal Relief Funds. Over the past two years, districts have used federal relief funds to cover various operating costs, including new COVID‑19 mitigation‑related costs. Once these federal relief funds are spent or otherwise expire, districts likely will assume responsibility for covering ongoing operating costs such as for personal protective equipment, additional cleaning, and potentially COVID‑19 screening and testing. Districts also will need to begin covering the technology costs (such as for computer equipment for students and staff as well as software licenses) that federal relief funds have been covering. In addition, a number of districts have used federal relief funds to backfill the loss of revenue from parking and other auxiliary programs. The loss of federal funds will put pressure on district operating budgets to cover these costs should revenues from these auxiliary programs fail to return to pre‑pandemic levels.

Recommendation

Make COLA Decision Once Better Information Is Available This Spring. The federal government will release the final data for the 2022‑23 COLA in late April 2022. By early May, the Legislature also will have better information on state revenues, which, in turn, will affect the amount available for new CCC Proposition 98 spending. If additional Proposition 98 ongoing funds are available in May, the Legislature may wish to provide a greater increase than the Governor’s January budget proposes for community college apportionments. A larger increase would help all community college districts to address salary pressures, rising pension costs, and other operating cost increases while also helping them adjust to the expiration of their federal relief funds.

Enrollment

In this section, we provide background on community college enrollment trends, describe the Governor’s proposal to increase funding for enrollment and student outreach, assess those proposals, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

Several Factors Influence CCC Enrollment. Under the state’s Master Plan for Higher Education and state law, community colleges operate as open access institutions. That is, all persons 18 years or older may attend a community college. (While CCC does not deny admission to students, there is no guarantee of access to a particular class.) Many factors affect the number of students who attend community colleges, including changes in the state’s population, particularly among young adults; local economic conditions, particularly the local job market; the availability of certain classes; and the perceived value of the education to potential students.

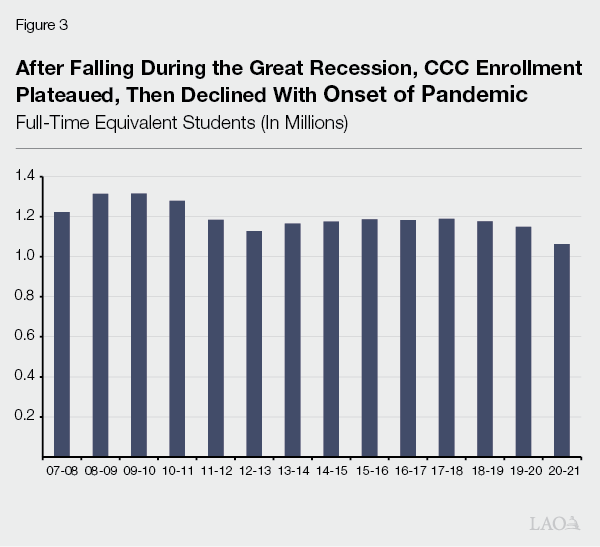

Prior to the Pandemic, CCC Enrollment Had Plateaued. During the Great Recession, community college student demand increased as individuals losing jobs sought additional education and training. Yet, enrollment ended up dropping as the state reduced funding for the colleges. A state funding recovered during the early years of the economic expansion (2012‑13 through 2015‑16), systemwide enrollment increased. Figure 3 shows that enrollment flattened thereafter, as the period of economic expansion continued and unemployment remained at or near record lows.

CCC Enrollment Has Dropped Notably Since Start of Pandemic. Consistent with nationwide trends for community colleges, between 2018‑19 (the last full year before the start of the pandemic) and 2020‑21, full‑time equivalent (FTE) students declined by 115,000 (10 percent), as also shown in Figure 3. While enrollment declines have affected virtually every student demographic group, most districts report the largest enrollment declines among African American, male, lower‑income, and older adult students. Data for 2021‑22 will not be finalized for many months, but preliminary fall 2021 data suggests enrollment could be down by more than 5 percent compared with the previous fall. Though most districts reporting as of early February 2022 show enrollment declines from fall 2020 to fall 2021, data indicate that a few districts could be starting to see some enrollment growth.

Several Factors Likely Contributing to Enrollment Drops. Enrollment drops nationally and in California have been attributed to various factors, including more student‑parents staying home to provide child care, public health concerns, and disinterest among some students to taking courses online. (As of fall 2021, about two‑thirds of colleges’ course sections were still being taught fully online.) Rising wages, including in low‑skill jobs, and an improved job market also could be reducing enrollment demand. In response to a fall 2021 Chancellor’s Office survey of former and prospective students, many respondents cited “the need to work full time” to support themselves and their families as a key reason why they were choosing not to attend CCC. For these individuals, enrolling in a community college and taking on the associated opportunity cost might have become a lower priority than entering or reentering the job market.

Colleges Have Been Trying a Number of Strategies to Attract Students. Using federal relief funds, as well as state funds provided in the 2021‑22 budget, colleges generally have been trying many tactics to attract students. Many colleges are using student survey data to adjust their course offerings and instructional modalities. Colleges are beginning to offer more flexible courses, with shorter terms and more opportunities to enroll throughout the year (rather than only during typical semester start dates). Colleges have been offering students various forms of financial assistance. For example, all colleges are providing emergency grants to financially eligible students, and some colleges are offering gas cards or book and meal vouchers to students who enroll. Many colleges are loaning laptops to students. Many colleges have expanded advertising through social media and other means. Additionally, many colleges have increased outreach to local high schools and created phone banks to contact individuals who recently dropped out of college or had completed a CCC application recently but did not enroll.

Proposals

Funds Enrollment Growth. The budget includes $25 million Proposition 98 General Fund for 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth (equating to about 5,500 additional FTE students) in 2022‑23. (The state also provided funding for 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth in 2021‑22.) Consistent with regular enrollment growth allocations, each district in 2022‑23 would be eligible to grow up to 0.5 percent. Provisional budget language would allow the Chancellor’s Office to allocate any ultimately unused growth funding to backfill any shortfalls in apportionment funding, such as ones resulting from lower‑than‑estimated enrollment fee revenue or local property tax revenue. The Chancellor’s Office could make any such redirection after underlying data had been finalized, which would occur after the close of the fiscal year. (This is the same provisional language the state has adopted in recent years.)

Proposes Another Round of One‑Time Funding to Boost Outreach to Students. The Governor proposes $150 million one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund for student recruitment and retention strategies. This is on top of the $120 million one time provided in the 2021‑22 budget ($20 million approved through early action and $100 million approved through the final budget package). Like the initiative funded last year by the Legislature, the purpose of these proposed funds is for colleges to reach out to former students who recently dropped out and engage with prospective or current students who might be hesitant to enroll or reenroll at the colleges. Provisional language gives the Chancellor’s Office discretion on the allocation methodology for the funds but would require that colleges experiencing the largest enrollment declines be prioritized. The provisional language also permits the Chancellor’s Office to set aside and use up to 10 percent of the funds for statewide enrollment and retention efforts. (The state adopted these same provisions for the $100 million approved as part of the final 2021‑22 budget package.)

Assessment

Better Information Is Coming to Inform Legislature’s Decision on Enrollment Growth. By the time of the May Revision, the Chancellor’s Office will have provided the Legislature with final 2020‑21 enrollment data and initial 2021‑22 enrollment data. This data will show which districts are reporting enrollment declines and the magnitude of those declines. It also will show whether any districts are on track to earn any of the 2021‑22 enrollment growth funds. If some districts are on track to grow in the current year, it could mean they might continue to grow in the budget year. Even if the entire amount ends up not being earned in the current year or budget year, remaining funds can be used to cover apportionment shortfalls. If no such shortfalls materialize, the funds become available for other Proposition 98 purposes, including other community college purposes.

Key Unknowns in Assessing One‑Time Funding Proposal. Assessing the Governor’s outreach proposal to fund additional student recruitment, reengagement, and retention is particularly challenging for a few reasons. First, the state does not know how much of last year’s student outreach allocation colleges have been spent or encumbered to date. (Colleges are not required to report this information to the state.) Second, the state has no clear way of deciphering how effective colleges’ spending in this area has been. Given continued enrollment declines, one might conclude that the funds have not achieved their goal of bolstering enrollment. Enrollment declines, however, might have been even worse without the 2021‑22 student outreach funds. Third, some factors driving enrollment changes—including the economy, current favorable job market, students’ need to care for family, and students’ risk calculations relating to COVID‑19—are largely outside colleges’ control. To the extent these exogenous factors are stronger in driving student behavior than college advertisements or phone banks, student outreach might not be a particularly promising use of one‑time funds.

Recommendations

Use Forthcoming Data to Decide Enrollment Growth Funding for 2022‑23. We recommend the Legislature use updated enrollment data, as well as updated data on available Proposition 98 funds, to make its decision on CCC enrollment growth for 2022‑23. If the updated enrollment data indicate some districts are growing in 2021‑22, the Legislature could view growth funding in 2022‑23 as warranted. Were data to show that no districts are growing, the Legislature still might consider providing some level of growth funding given that enrollment potentially could start to rebound next year. Moreover, the risk of overbudgeting in this area is low, as any unearned funds become available for other Proposition 98 purposes.

Weigh Options on One‑Time Funds. To the extent the Legislature thinks colleges can effectively implement strategies to recruit students who otherwise would not have enrolled, it could approve the Governor’s student outreach proposal. The Legislature, however, could weigh funding for this proposal against other one‑time spending priorities for community colleges. For example, were the Legislature concerned about colleges’ ability to cover continued COVID‑19‑related costs in 2022‑23 given the expiration of federal relief funds, it could create a COVID‑19 block grant. Such an approach would give colleges more flexibility to put funds where they may be the most effectively used, such as for student recruitment, mental health services, or COVID‑19 mitigation.

Student Centered Funding Formula

In this section, we provide background on CCC’s apportionment formula, describe the Governor’s proposal to modify it, assess the proposal and formula more broadly, and provide recommendations aimed at improving the formula.

Background

State Adopted New Apportionment Funding Formula in 2018‑19. For a number of years, the state allocated general purpose funding to community colleges based almost entirely on enrollment. Districts generally received an equal per‑student funding rate. Student funding rates were not adjusted according to the type of student served or whether students ultimately completed their educational goals. In 2018‑19, the state moved away from that funding model. In creating SCFF, the state placed less emphasis on seat time and more emphasis on students achieving positive outcomes. The new funding formula also recognized the additional cost that colleges have in serving students who face higher barriers to success (due to income level or other factors). Another related objective was to provide a strong incentive for colleges to enroll low‑income students and ensure they obtain financial aid to support their educational costs.

New Formula Has Three Main Components. The components are: (1) a base allocation linked to enrollment, (2) a supplemental allocation linked to low‑income student counts, and (3) a student success allocation linked to specified student outcomes. We describe these components in more detail in the next three paragraphs. For each of the three components, the state set new funding rates, with the rates to increase in years in which the Legislature provides a COLA. The new formula does not apply to incarcerated students or dually enrolled high school students. It also does not apply to students in noncredit programs. Apportionments for these students remain based entirely on enrollment.

Base Allocation. As with the prior apportionment formula, the base allocation of SCFF gives a district certain amounts for each of its colleges and state‑approved centers, in recognition of the fixed costs entailed in running an institution. (This funding for fixed institutional costs is known as districts’ “basic allocation.”) On top of that allotment, it gives a district funding for each credit FTE student (about $4,200 in 2021‑22). Calculating a district’s FTE student count involves several somewhat complicated steps, but basically the count is based on a three‑year rolling average. The rolling average takes into account a district’s current‑year FTE count and counts for the prior two years.

Supplemental Allocation. SCFF provides an additional amount (about $1,000 in 2021‑22) for every student who receives a Pell Grant, receives a need‑based fee waiver, or is undocumented and qualifies for resident tuition. Student counts are “duplicated,” such that districts receive twice as much supplemental funding (about $2,000 in 2021‑22) for a student who is included in two of these categories (for example, receiving both a Pell Grant and a need‑based fee waiver). The allocation is based on student counts from the prior year. In 2019, an oversight committee made a recommendation to add a new factor to the supplemental allocation (as well as the student success allocation), as described in the box nearby.

Oversight Committee Recommendation

Committee Was Charged With Studying Possible Modifications to Funding Formula. The statute that created the Student Centered Funding Formula also established a 12‑member oversight committee, with the Assembly, Senate, and Governor each responsible for choosing four members. The committee was tasked with reviewing and evaluating initial implementation of the new formula. It also was tasked with exploring certain changes to the formula over the next few years, including whether the supplemental allocation should consider first‑generation college status and incoming students’ level of academic proficiency. Statute also directed the committee to consider whether low‑income supplemental rates should be adjusted for differences in regional cost of living. The committee officially sunset on January 1, 2022.

Committee Recommended Adding First‑Generation College Status to Formula. In December 2019, the committee recommended that counts of first‑generation college students be added to the supplemental allocation as well as the student success allocation. The committee recommended defining “first generation” as a student whose parents do not hold a bachelor’s degree. (Currently, community colleges define first generation as a student whose parents do not hold an associate degree or higher.) The oversight committee recommended using an “unduplicated” count of first‑generation and low‑income students. (This means a student who is both a first‑generation college goer and low income would be counted as one for purposes of generating supplemental funding.) Oversight committee members ultimately rejected or could not agree on the issues of adding incoming students’ academic proficiency and a regional cost‑of‑living adjustment to the formula.

Student Success Allocation. The formula also provides additional funding for each student achieving specified outcomes, including obtaining various degrees and certificates, completing transfer‑level math and English within the student’s first year, and obtaining a regional living wage within a year of completing community college. (For example, a district generates about $2,350 in 2021‑22 for each of its students receiving an associate degree for transfer. The formula counts only the highest award earned by a student.) Districts receive higher funding rates for the outcomes of students who receive a Pell Grant or need‑based fee waiver, with somewhat greater rates for the outcomes of Pell Grant recipients. The student success component of the formula is based on a three‑year rolling average of student outcomes. The rolling average takes into account outcomes data from the prior year and two preceding years.

Statute Weights the Three Components of the Formula. Of total apportionment funding, the base allocation accounts for approximately 70 percent, the supplemental allocation accounts for 20 percent, and the student success allocation accounts for 10 percent.

New Formula Impacted Districts Differently. The 2018‑19 budget provided a $175 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund augmentation (above the apportionments COLA that year) to transition to SCFF. The funding increase (equating to less than 3 percent that year) was in recognition of the slightly higher cost of the new formula. The impact of the new formula on district funding levels varied. Primarily because SCFF provides additional funding for districts serving financially needy students, a number of districts in high‑poverty areas of the state (such as in several rural areas of the state and various districts in the Central Valley) generated up to 20 percent increases in their apportionment funding compared with their allocations under the former funding formula. Other districts—mainly concentrated in more affluent areas of the state (such as the Bay Area and Coastal California)—generated about the same or even somewhat less funding under SCFF than how they fared under the former formula. (So‑called “basic aid” or “fully community‑supported” districts whose revenues from local property taxes and enrollment fees are in excess of their total allotment under the funding formula do not receive their funding based on SCFF’s rules. In 2020‑21, the CCC system had eight such districts. In addition, CCC’s 73rd and newest district, Calbright College, is funded entirely through a categorical program.)

Temporary Hold Harmless Provision Intended to Ease Transition to New Formula. The new funding formula included a temporary “hold harmless” provision for those districts that would have received more funding under the former apportionment formula. The intent of the hold harmless protection was to provide time for those districts to ramp down their budgets to the new SCFF‑generated funding level or find ways to increase the amount they generate through SCFF (such as by enrolling more financially needy students or improving student outcomes).

Sunset Date of Hold Harmless Provision Has Been Extended Multiple Times. Districts funded according to this hold harmless provision receive whatever they generated in 2017‑18 under the old formula, plus any subsequent apportionment COLA provided by the state. The original hold harmless provision was scheduled to expire at the end of 2020‑21. The 2019‑20, 2020‑21, and 2021‑22 budgets all extended when the hold harmless provision would end. Currently, it is scheduled to expire at the end of 2024‑25. After that, statute generally stipulates those districts are to be funded annually based on the higher of (1) what they generate under SCFF or (2) the per‑student rate they received in 2017‑18 under the former apportionment formula (which was $5,150 for most districts) multiplied by their current FTE student count. Based on preliminary data, in 2020‑21, about 20 of CCC’s 64 local nonbasic‑aid districts received a total of about $160 million in hold harmless funds. (In other words, these districts collectively received about $160 million more than they generated under SCFF.)

Certain Aspects of Formula Have Been Temporarily Modified. While statute specifies the years of data that are to be used to calculate the amount a district receives under SCFF (that is, for districts that are not on hold harmless or basic aid districts), state regulations provide the Chancellor’s Office with authority to use alternative years of data in extraordinary cases. Known as the “emergency conditions allowance,” the Chancellor’s Office has been allowing districts to use alternative (pre‑pandemic) enrollment data for 2019‑20, 2020‑21, and 2021‑22. The purpose of this emergency conditions allowance is to prevent districts from having their apportionment funding reduced due to enrollment drops resulting from the pandemic. (The emergency conditions allowance is only on the enrollment component of the SCFF. The supplemental and student success allocations continue to be based on the years specified in statute.) While final 2020‑21 data will not be released by the Chancellor’s Office until late February 2022, we estimate that about 40 of CCC’s 64 local nonbasic‑aid districts will have claimed COVID‑19 emergency conditions allowance that year—likely providing them with a total of between $150 million and $200 million in funding protections. It is likely that about the same number are claiming the COVID‑19 emergency conditions allowance in 2021‑22. (Currently, four other districts can claim emergency conditions allowances for other extraordinary situations, such as from enrollment losses resulting from wildfires.)

Chancellor’s Office Is Analyzing Data to Determine a Possible Emergency Conditions Allowance for 2022‑23. In spring 2021, the Chancellor’s Office issued a memo to community colleges signaling its intent to extend the COVID‑19 emergency conditions allowance “for one final year” in 2021‑22. According to the Chancellor’s Office, the Board of Governors, which has the regulatory authority to adopt emergency conditions allowances, will revisit whether to extend the emergency conditions allowance in spring 2022. The decision about whether to extend the allowance through 2022‑23 will be based on an examination of districts’ current‑year enrollment trends, actions taken by districts to mitigate enrollment declines, and the health safety conditions in the state.

Proposals

Proposes to Change Hold Harmless Provision. The Governor is concerned that districts funded according to the existing hold harmless provision are on track to experience fiscal declines when the provision expires at the end of 2024‑25. To address this issue, the Governor proposes to create a new funding floor based on districts’ hold harmless level at the end of 2024‑25. Specifically, he proposes that, starting in 2025‑26, districts be funded at their SCFF‑generated amount that year or their hold harmless amount in 2024‑25, whichever is higher. Whereas SCFF rates would continue to receive a COLA in subsequent years, a district’s hold harmless amount would not grow. The intent is to eventually get all districts funded under SCFF, with SCFF‑generated funding levels over time surpassing districts’ locked‑in‑place hold harmless amounts.

Supports Adding First‑Generation Metric to SCFF. The Governor also signals his interest in adopting the oversight committee’s recommendation to incorporate first‑generation college students into SCFF. Consistent with the committee’s recommendation, the metric would be an unduplicated count (with a first‑generation student who is also low income counting once for SCFF purposes). The Department of Finance indicates that colleges currently may not be collectively or uniformly reporting this data to the Chancellor’s Office. (Currently, districts are relying on students self‑identifying as first generation, and districts are not consistently reporting this information to the Chancellor’s Office.) The Governor thus expresses his support to add this metric once “a reliable and stable data source is available.”

Does Not Address Question of Further Extending Emergency Conditions Allowance. The Governor’s budget does not include any proposal related to extending the COVID‑19 emergency conditions allowance. In our discussions, the administration has noted that the Board of Governors already has the authority to do so and has not taken a position one way or another on the issue for 2022‑23.

Assessment

In Proposing a New Funding Floor, Governor’s Goal Is Laudable. Based on preliminary 2020‑21 Chancellor’s Office data, hold harmless districts generally are funded notably above the amount they generate through SCFF. These districts thus potentially face a sizeable “fiscal cliff” in 2025‑26 when their current‑law hold harmless provision expires. (These districts’ funding declines could be made worse were their enrollment not to recover to pre‑pandemic levels.) We share the Governor’s concern that having districts cut their budgets to such a degree likely would be disruptive to students and staff. A better approach would be to have a more gradual reduction, which the Governor is attempting to accomplish with his hold harmless proposal.

Hold Harmless Funding Creates Poor Incentives for Districts. At the same time, being funded according to the Governor’s proposed hold harmless provision creates poor incentives. The poor incentives stem from districts receiving funding regardless of the number of students they serve, the type of students they enroll, or the outcomes of those students. That is, the hold harmless provision does not promote the state’s value of promoting access, equity, and student success. Moreover, some districts under the Governor’s proposal will remain funded under the hold harmless provision for several years. (The exact length of time will depend on how each district’s enrollment changes, how far districts’ hold harmless level is currently above SCFF, and the size of future apportionment COLAs.) In the meantime, those districts would not receive funding based on workload and performance. Instead, they would continue to have limited incentives to meet student enrollment demand, offer courses in the modality and during the times of day students prefer, and innovate in ways that improve student outcomes. All this time, these districts would be funded at higher per‑student rates than their district peers without an underlying rationale.

Merit to Adding First‑Generation College Goers as a Metric. Although some needs of first‑generation college students may be similar to those of low‑income students, first‑generation students also have distinct needs. National research finds that although nonfinancially needy first‑generation community college students may not have financial barriers, they often lack what is referred to as “college knowledge”—knowledge of how to make curricular choices, how to consult with faculty, and how to navigate often complex transfer pathways and other program requirements. Since first‑generation students do not have family members with specific knowledge of the college landscape who can offer assistance on how to navigate through the college system, these students may require additional support from their community colleges. By adding first‑generation status as a metric, the state could provide districts with funds to better help these students.

Districts Currently Protected by Emergency Conditions Allowance Could Lose Enrollment Funding. Were the Board of Governors not to extend the emergency conditions allowance in 2022‑23, districts that do not grow back to pre‑pandemic enrollment levels in 2022‑23 would generate less enrollment funding in 2023‑24 than they are currently receiving. (Due to a statutory funding protection known as “stability,” these districts would receive their 2021‑22 SCFF funding level, plus any COLA, in 2022‑23. Beginning in 2023‑24, however, their SCFF allocation would reflect their lower enrollment levels.) The Legislature may wish to consider whether it would like districts to begin adjusting their budgets in response to current enrollment conditions or provide districts another year to see if they can increase their enrollment levels.

Increasing SCFF Base Rate Would Have Several Key Benefits. Increasing the SCFF base rate would help colleges in addressing several challenges. Not only would a higher base rate help districts respond to salary and pension pressures (as discussed in the “Apportionments Increase” section of this brief), but it also could help districts facing enrollment declines (as it would soften associated funding declines). Moreover, raising the base rate would have the effect of eliminating hold harmless funding more quickly. Districts would begin generating funding under SCFF sooner, and, in turn, their incentives to serve students would be stronger sooner. A higher base rate also could result in no district receiving less funding under SCFF compared to the former funding model—perhaps helping to bolster support of the formula itself and its focus on student outcomes and support.

Recommendations

Modify Governor’s Hold Harmless Proposal by Setting a New Base SCFF Target. We recommend the Legislature begin exploring the possibility of raising base SCFF funding. Two options for raising base funding are to increase the base per‑student rate and/or increase the basic allocation all districts receive to address their fixed costs. In deciding how much to increase base funding, the Legislature might consider various factors, including colleges’ core cost drivers and student improvement goals. After deciding how to increase SCFF base funding and settling on a new level of base funding, the Legislature then could develop a plan for reaching the higher funding level, with the plan potentially stretching across several years. If the Legislature desired, it could start moving toward those higher rates in 2022‑23 by redirecting some of the ongoing funds the Governor has proposed in his January 10 budget. (In the next section of this brief, we identify a potential area where the Legislature might free up ongoing Proposition 98 funds for this purpose.)

Also Move Toward Adding First Generation as a Metric. Once data are consistently reported by districts, the Legislature could further refine SCFF by adding a first‑generation student metric to the SCFF supplemental and student success allocations, as recommended by the SCFF Oversight Committee. Were the Legislature to increase the SCFF base rate, it likely could integrate first generation as a metric into the formula while still preserving the overall 70/20/10 split among SCFF’s three allocation components. Modeling how much to adjust the underlying SCFF rates will become easier once data on the counts of first‑generation students becomes available. In the meantime, the Legislature could direct the Chancellor’s Office to work with the colleges to improve data collection in this area.

Direct Chancellor’s Office to Provide Update on Emergency Conditions Allowance Decision. Finally, we recommend the Legislature request the Chancellor’s Office to clarify its intentions for next year with regard to the emergency conditions allowance. In particular, the Legislature should gain clarity on the specific criteria the Board of Governors intends to use in making such a determination. We recommend the Legislature direct the Chancellor’s Office to report this information to the Legislature at spring hearings.

Part‑Time Faculty Health Insurance

In this section, we provide background on the Part‑Time Faculty Health Insurance Program, describe the Governor’s proposal to provide the program a sizeable augmentation, assess the proposal, and make an associated recommendation.

Background

Below, we provide background on faculty at the community colleges, district health care plans, and state requirements regarding health insurance.

Faculty

Instruction at CCC Is Provided by a Mix of Full‑Time and Part‑Time Faculty. Instruction at the community colleges is provided by nearly 20,000 full‑time faculty and about 35,000 part‑time faculty. Districts generally require full‑time faculty to teach 15 units (credit hours) per semester (commonly five three‑unit classes). Full‑time faculty are either tenured or on tenure‑track and are considered permanent employees of the district. In contrast, districts can decide whether to retain part‑time faculty, who are considered temporary employees, for any given term depending on course scheduling and other considerations. Statute limits part‑time faculty to teaching 67 percent of a full‑time load at a given district (about ten units per semester or about three classes). Many part‑time faculty maintain an outside job, some are retired and teaching only a course or two, and others teach part time at two or more districts (with their combined teaching load potentially equaling, or even exceeding, a full‑time teaching load).

Faculty Compensation Collectively Bargained at Local Level. Both full‑time and part‑time CCC faculty generally are represented by unions. Each district and its faculty group (or groups) collectively bargain salary levels and benefits. (In some districts, full‑time and part‑time faculty are part of the same bargaining unit. In other districts, they are in separate bargaining units.)

Pay for Full‑Time Faculty Is Much Higher Than for Part‑Time Faculty. In 2020‑21, full‑time faculty were paid an average of $105,000 annually. On average, districts paid part‑time faculty $60 per hour of instruction, with a range between $20 per hour at the low end and $80 per hour at the upper end. (Part‑time faculty generally are not compensated for time they spend in preparation for classes or grading assignments.) Based on average pay, a part‑time faculty member teaching three three‑unit courses (nine hours per week) both in the fall and spring semester would earn about $19,000 per year.

Community College Health Care Plans

Districts Provide Health Insurance to Full‑Time Faculty. All districts provide some level of funding for health care benefits for full‑time faculty. Typically, the district offers several medical plan options (with various costs and coverage levels) and agrees to contribute a set amount toward premium costs, with a larger amount provided if the employee has a spouse or family. (A premium is the amount paid to an insurance company to have a health insurance plan. Health insurance plans also typically have patient copays and deductibles, which reflect direct out‑of‑pocket costs. For example, a plan might charge a patient a set amount for a particular medical service or hospital stay.) In many districts, the amount the district contributes covers the full or nearly full premium cost of the lowest‑price plan for full‑time faculty and all or most of the cost for the faculty’s spouse and dependents. Employees are responsible for covering any remaining insurance premium costs not paid for by the district. In addition, districts often cover the full cost of dental and vision insurance for full‑time faculty, with coverage also being extended to the faculty’s dependents. Districts generally cover these health insurance costs using their unrestricted apportionment funding.

Decades Ago, Legislature Created a Program to Promote Part‑Time Faculty Health Insurance. Part‑time faculty collective bargaining agreements historically have not included district funding for health care benefits. In an effort to create an incentive for districts to negotiate and provide subsidized health care for part‑time faculty, in the 1990s the Legislature created the Part‑Time Faculty Health Insurance Program. For this program, part‑time faculty are defined as those with teaching assignments equal to or greater than 40 percent of a full‑time assignment (typically about two courses). Through collective bargaining, districts and faculty representatives decide what health coverage to offer (such as whether to extend coverage to an employee’s family). They also decide the share of health premiums to be covered by the district and the employee. The program does not cover dental or vision insurance.

Program Designed to Cover a Portion of District Costs. The program reimburses districts (the employer) for up to half of their health insurance premium costs provided to part‑time faculty. The Chancellor’s Office determines the exact share of district premiums to cover based upon the annual budget appropriation for the program. Districts generally cover remaining costs using their unrestricted apportionment funding. For years, funding for the categorical program was $1 million ongoing. Due to the state’s fiscal condition during the Great Recession, the program’s budget was reduced to $490,000 in 2009‑10. The program has been funded at $490,000 ongoing since that time.

Almost Half of Districts Participate but Program Covers Small Share of District Costs. Figure 4 shows that in 2020‑21, 33 of CCC’s 72 local districts submitted claims to the Chancellor’s Office for reimbursement under the program. (Systemwide data are not available on all districts offering health insurance to part‑time faculty. Some districts, however, do offer insurance to part‑timers without seeking state reimbursement for a portion of those costs.) Just under 3,700 part‑time faculty received health care coverage from these districts (about 10 percent of all part‑time faculty). On average, districts covered about 80 percent of the $31 million in total premium costs, with part‑time faculty paying the remaining amount. Program reimbursements covered about 2 percent of districts’ premium costs.

Figure 4

Summary of Part‑Time Faculty

Health Insurance Program

2020‑21

|

Number of districts participating |

33 |

|

Share of local districts participating |

46% |

|

Number of part‑time faculty participating |

3,691 |

|

Share of total part‑time faculty participating |

About 10 percent |

|

Total premium costs |

$31,481,326 |

|

Premium cost paid by district |

$24,722,739 |

|

Premium cost paid by employee |

$6,268,587 |

|

Annual program funding |

$490,000 |

|

Percent of district premium cost covered by program |

2% |

Considerable Variation in Coverage Districts Offer to Part‑Time Faculty. Among districts participating in the program in 2020‑21, the amount of premium costs covered by the district ranged from 100 percent to under 30 percent. That is, participating part‑time faculty in these districts paid between 0 percent to more than 70 percent of premium costs. In some cases, the amount the district covers for the insurance premium is based on a sliding scale of how many units a part‑time faculty teaches, with a lower share of cost provided for those teaching fewer units or classes. Based on our discussions with the California Federation of Teachers and several districts, the insurance offered to part‑time faculty varies significantly across the CCC system in other ways too. For example, some districts offer the same medical plans to part‑time faculty as the full‑time faculty, whereas part‑time faculty in other districts are limited to choosing medical plans with less coverage or higher out‑of‑pocket costs. Some districts cover only the employee (known as “self only” coverage), whereas other districts offer at least some level of coverage to the employee’s spouse and dependents too. Districts vary as well in the number of terms a part‑time faculty member must teach in a row (or within a certain period of time) to be eligible for a district‑provided plan.

State Health Insurance Requirements

Most Californians Have Health Insurance. Since 2020, state law has required all adults and their dependents to have health insurance—a requirement commonly known as the “individual mandate.” State residents who choose to go without health insurance generally face a state tax penalty. Roughly 90 percent of Californians have health insurance. Most insured Californians receive their health insurance through their employer. In addition, Medi‑Cal offers free or low‑cost medical coverage to qualifying low‑income adults and children in the state. Older adults generally are eligible for Medicare, a federal program that provides health insurance primarily for persons 65 years or older. California also has a state‑run service, known as Covered California, as discussed below.

Health Insurance Available Through Covered California. California residents who do not receive health care coverage through their employers, spouse, or from other government programs can purchase insurance that meets established quality standards through a central health insurance marketplace known as the California Health Benefit Exchange (Covered California). Residents who meet certain qualifications (including having income below a specified level) can receive subsidized premiums and other financial assistance when they purchase an insurance plan through Covered California.

Rules Around Who Can Qualify for Premium Subsidies Under Covered California. Importantly, if a person’s employer provides a health plan that is deemed affordable to the employee and provides a specified minimum level of coverage, the employee cannot qualify for subsidies (for themselves or their families) through Covered California. (In such cases, a person can still purchase health insurance through Covered California but would pay the full cost of the plan.) Currently, employer‑provided insurance is considered affordable by the federal government if the employee’s share of the annual self‑only premium for the lowest‑priced plan costs less than 9.6 percent of the employee’s household income. If the employer offers a plan that meets this definition of affordable (and meets certain other standards) but the employee turns it down and receives financial help through a Covered California plan, the employee has to pay back the Covered California subsidy when filing state and federal taxes.

“Family Glitch” Has Negative Implications for Some Employees. Importantly, affordability is based on the cost of a plan to cover the employee only—not the cost of the plan that would also cover their spouse or dependents. If the employer contributes little to nothing for the spouse’s and dependent’s premium, some employees may find adding family members to the employer‑sponsored plan financially prohibitive. Nonetheless, the family remains ineligible for financial assistance through Covered California (as the district still offered insurance to the employee). This outcome is often referred to as the family glitch.

Proposal

Governor Proposes $200 Million Ongoing Augmentation for Part‑Time Faculty Health Insurance Program. With a current program funding level of $490,000, the proposed augmentation represents a 400‑fold increase—the largest ongoing CCC augmentation in percentage terms by far. The proposed augmentation would result in this program shifting from being one of the smallest CCC categorical programs to one of the largest. The Governor’s stated intent in providing the large augmentation is to create a stronger financial incentive for more community college districts to provide medical care coverage to their part‑time faculty. The Governor does not propose any other changes to the program itself.

Assessment

Problem Is Unclear. The Governor indicates an interest in expanding medical coverage for part‑time faculty. The administration, however, has not yet provided any data on the number of part‑time faculty who do not have health insurance. The administration also has not provided any data on the share of part‑time faculty who access health insurance through an outside job, spouse, Medi‑Cal, Medicare, or Covered California. (District administrators we spoke with believed that most part‑time faculty have health insurance through one of these means.) Without these data, determining whether a problem exists involving health care access or affordability is not possible.

Some District‑Provided Health Care Coverage May Be Disadvantaging Certain Part‑Time Faculty. Some part‑time faculty working in districts that offer health insurance could be worse off than had their district not offered health care. This is particularly the case if employers provide plans that keep premium costs for the employee to less than 9.6 percent of household income but provide little or no contribution toward covering the employee’s family. In such cases, coverage through the district‑provided plan for a spouse or dependents might cost more than coverage through a Covered California plan. Nonetheless, the availability of the district plan for the employee would prevent the family from receiving financial assistance if they enroll in a Covered California plan due to the family glitch. In such circumstances, the family could have higher health insurance costs than if no district‑provided plan had been offered. Like other related data in this area, the administration has not yet provided data on how many part‑time faculty are being negatively affected in this way.

Part‑Time Faculty Face Greater Uncertainty With District‑Provided Coverage. Given declining enrollment across the CCC system, districts have been reducing course section offerings. These reductions mean fewer teaching opportunities for part‑time faculty. If part‑time faculty are not hired or fall below a certain number of teaching units, they stand to lose district‑provided health care or see an increase in their premium costs. Even were districts to offer robust coverage for part‑time faculty and their families, the Legislature thus faces the policy question of whether this CCC program is the best way to provide them health insurance—with part‑time faculty potentially fluctuating in and out of district‑provided coverage. Potentially having to change health plans frequently might be less optimal for part‑time faculty than remaining insured under Covered California.

Proposal Raises Equity Issues for Other Part‑Time Workers in State. California has many part‑time employees throughout state and local government. Yet, the state generally does not fund a special health care program for these other groups. Expanding a program for part‑time CCC faculty thus could create an inequity relative to other part‑time workers. Also, such a major expansion of the current program for CCC part‑time faculty could set a greater precedent for dealing with each group of part‑time workers separately, potentially introducing further inequities.

Proposal May Not Be the Best Approach to Improve Health Care Affordability. If the goal is to improve health care affordability and statewide coverage, the Governor’s proposal might not be the best approach as it likely would only impact a relatively small number of residents. Notably, a recent report from Covered California highlights various options to offer increased financial assistance to a much broader group of Californians than this proposal, with state costs ranging from $37 million to $452 million. These options are designed to reduce or eliminate various health care costs (such as the amount patients must pay for certain medical services and the maximum they are required to pay out‑of‑pocket in a given year) for low‑ and middle‑income Californians who have purchased health plans through Covered California. (Our forthcoming publication, The 2022‑23 Budget: Analysis of Health Care Access and Affordability Proposals, will provide additional details and assessment of these options.)

Recommendation

More Information Is Needed to Assess How Best to Enhance Health Coverage. The Legislature needs additional information if it is to assess the implications of the Governor’s proposal. In particular, the Legislature needs clarification about what problem the administration is trying to solve, the extent of the problem, and why the proposal in the Governor’s budget is the most optimal solution. The Legislature also needs information allowing it to compare the health coverage for part‑time faculty to other part‑time workers in the state. Without this information, moving forward with the Governor’s proposal could have unintended, counterproductive effects—potentially exacerbating rather than mitigating health coverage inequities. Furthermore, gathering more information on these issues likely would take several months, making budget action for 2022‑23 impractical.

Legislature Could Task Administration With Providing This Information. If the Legislature is interested in enhancing health coverage for part‑time workers, it could direct the administration, in coordination with the Chancellor’s Office, to obtain more information on the insured status of part‑time faculty and on the part‑time faculty health care plans currently offered by districts. The Chancellor’s Office could survey part‑time faculty and districts to learn, at a minimum:

- What percent of part‑time faculty have health insurance? What is the source of their health insurance?

- What factors are driving whether districts offer health insurance to part‑time faculty and what factors are driving the type of coverage they provide?

- For districts that offer health insurance to part‑time faculty, does the coverage extend to the employee’s family? If so, how much of the premium is covered by the district? How many part‑time faculty are on this type of coverage?

The Legislature similarly could direct the administration to work with other state agencies to gather comparable information for other part‑time workers in the state. The Legislature could give the administration until October 2022 to submit this information. With such information, both the administration and Legislature would be much better positioned to inform potential budget decisions for 2023‑24 and decide how best to enhance health coverage for part‑time workers in California.

Facility Maintenance

In this section, we provide background on CCC’s maintenance backlog and maintenance categorical program, describe the Governor’s proposal to fund deferred maintenance and other projects, assess the proposal, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

CCC Maintains Inventory of Facility Conditions. Community college districts jointly developed a set of web‑based project planning and management tools called FUSION (Facilities Utilization, Space Inventory Options Net) in 2002. The Foundation for California Community Colleges (the Foundation) operates and maintains FUSION on behalf of districts. The Foundation employs assessors to complete a facility condition assessment of every building at districts’ campuses and centers on a three‑ to four‑year cycle. These assessments, together with other facility information entered into FUSION, provide data on CCC facilities and help districts with their local planning efforts.

State Has a Categorical Program for Maintenance and Repairs. Known as “Physical Plant and Instructional Support,” this program allows districts to use funds for facility maintenance and repairs, the replacement of instructional equipment and library materials, hazardous substances abatement, architectural barrier removal, and water conservation projects, among other related purposes. To use this categorical funding for maintenance and repairs, districts must adopt and submit to the CCC Chancellor’s Office through FUSION a list of maintenance projects, with estimated costs, that the district would like to undertake over the next five years. In addition to these categorical funds, CCC districts fund maintenance from their apportionments and other district operating funds (for less expensive projects) and from local bond funds (for more expensive projects). Statute requires districts to spend at least 0.5 percent of their current general operating budget on ongoing maintenance. Statute also contains a maintenance‑of‑effort provision requiring districts to spend annually at least as much on facility operations and maintenance as they spent in 1995‑96 (about $300 million statewide), plus what they receive from the Physical Plant and Instructional Support program. (Given inflation since 1995‑96, coupled with the 0.5 percent general operating budget requirement, districts tend to be spending far above this maintenance‑of‑effort level.)

State Has Provided Substantial Funding for Categorical Program Over Past Several Years. Historically, the Physical Plant and Instructional Support categorical program has received appropriations when one‑time Proposition 98 funding is available and no appropriations in tight budget years. Since 2015‑16, the Legislature has provided a total of $955 million for the program. The largest appropriation came from the 2021‑22 budget, which provided a total of $511 million. According to the Chancellor’s Office, thus far districts have chosen to use nearly three‑quarters (about $365 million) of these 2021‑22 funds for deferred maintenance and other facility‑related projects, with the remaining one‑quarter of funds intended for instructional support purposes.

Even With Recent Funding, Chancellor’s Office Reports Sizeable Maintenance Backlog. Entering 2021‑22, the Chancellor’s Office reported a systemwide deferred maintenance backlog of about $1.6 billion. Because of the funds provided in the 2021‑22 budget (plus local spending on projects), the backlog has been reduced to about $1.2 billion. This is the same size as the CCC backlog identified back in 2017‑18. Since that time, state funding effectively has kept the backlog from growing but not shrunk it.

Proposal

Governor Proposes $388 Million One Time for Physical Plant and Instructional Support Program. Of this amount, $109 million is 2022‑23 Proposition 98 General Fund and a total of $279 million is Proposition 98 settle‑up funds ($182 million attributed to 2021‑22 and $97 million attributed to 2020‑21). The Governor excludes all $388 million from SAL. In addition to the categorical program’s existing allowable purposes, proposed trailer language would allow districts to use the funds for energy efficiency projects. Districts would have until June 30, 2024 to encumber the funds.

Assessment

Proposal Reflects a Prudent Use of One‑Time Funding. Providing funds for deferred maintenance projects would address an existing need among districts. Addressing this need can help avoid more expensive facilities projects, including emergency repairs, in the long run. Funding energy efficiency projects also could be beneficial, as these projects are intended to reduce districts’ utility costs over time. In addition, instructional equipment and related support is core to CCC’s mission of delivering quality educational services to students.

One‑Time Funding Does Not Address Underlying Cause of Backlog. Deferred maintenance backlogs tend to emerge when districts do not consistently maintain their facilities and infrastructure on an ongoing basis. Although one‑time funding can help reduce the backlog in the short term, it does not address the underlying ongoing problem of underfunding in this area. Though districts are required to spend a certain share of their general operating funds on ongoing maintenance, the current rate (0.5 percent) may not be sufficient given the maintenance backlog exists and would have grown absent state categorical funding the past several years.

Recommendations

Consider Governor’s Proposal as a Starting Point. To address CCC’s maintenance backlog, we recommend the Legislature provide at least the $388 million proposed by the Governor. As it deliberates on the Governor’s other one‑time proposals and receives updated revenue information on the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee in May, the Legislature could consider providing CCC with more one‑time funding for this purpose.

Consider Developing Strategy to Address Ongoing Maintenance Needs. In addition to providing one‑time funding for deferred maintenance, we encourage the Legislature to begin developing a long‑term strategy around CCC maintenance. Potential issues to consider include whether the current statutory expectation around district spending on maintenance is sufficient, what fund sources to use for maintenance, the mix of funding provided ongoing versus on a one‑time basis, the period over which to address the existing maintenance backlog, and associated reporting. Given the magnitude of maintenance needs at CCC, developing such a strategy would likely require planning beyond the 2022‑23 budget cycle.