LAO Contact

February 15, 2022

The 2022‑23 Budget

California State University

- Introduction

- Overview

- Base Support

- Enrollment

- Foster Youth Programs

- Facility Maintenance

- Climate‑Related Capital Projects

Summary

Brief Covers All of Governor’s Funding Proposals for the California State University (CSU). This brief analyzes the Governor’s proposals for CSU base support, enrollment, foster youth programs, facility maintenance, and climate‑related initiatives.

Legislature Could Tie Base Augmentation More Closely to Anticipated Cost Increases. The Governor proposes a $211 million (5 percent) unrestricted General Fund base increase for CSU in 2022‑23. We recommend the Legislature replace this unrestricted base increase with an augmentation linked to specific cost increases. For illustration, at the Governor’s proposed funding level, the Legislature could cover CSU’s employee benefit cost increases, its previously negotiated salary increases, an approximately 3 percent increase in the salary pool for other employee groups, and certain other operating costs identified by CSU.

Legislature Faces Two Key Enrollment Decisions. Because of an unexpected enrollment decline in 2021‑22, CSU is projected to enroll fewer students in 2022‑23 than it enrolled two years earlier. In light of the updated enrollment data, the Legislature may wish to reconsider providing CSU enrollment growth funding in 2022‑23. Moving forward, we recommend the Legislature set a 2023‑24 enrollment target for CSU and indicate its intent to provide associated enrollment growth funding (rather than having CSU accommodate the growth from within its base support as the Governor proposes for that year).

Facility Maintenance Remains Underfunded at CSU. The Governor’s budget proposes $100 million one time for deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects at CSU. CSU estimates an existing maintenance backlog of $5.8 billion, as well as an annual ongoing capital renewal need of $284 million to keep the backlog from growing. For comparison, CSU estimates spending an average of $182 million annually on maintenance. The Governor’s proposal is a prudent use of one‑time funds, and we recommend the Legislature adopt at least the amount proposed. However, the Governor’s proposal still would not be addressing the ongoing problem of underfunding in this area. We encourage the Legislature to begin developing a long‑term strategy for addressing CSU’s ongoing maintenance and renewal needs.

Governor’s CSU Climate‑Related Initiatives Lack Strong Rationale. The Governor proposes $81 million one time to construct the CSU Bakersfield Energy Innovation Center and $50 million one time to upgrade equipment and facilities at CSU’s four university farms. Although the Governor links these proposals to climate objectives, climate‑related benefits appear to be a small component of both proposals. Moreover, neither proposal reflects the highest capital outlay priorities at CSU. The Legislature could consider redirecting these proposed funds to higher one‑time spending priorities.

Introduction

Brief Focuses on the California State University (CSU). CSU is one of California’s three public higher education segments. Its 23 campuses provide undergraduate, teacher preparation, and graduate education across a range of disciplines. CSU generally offers degrees through the master’s level, while also providing doctorates primarily in a few applied fields. This brief is organized around the Governor’s 2022‑23 budget proposals for CSU. The first section of the brief provides an overview of the Governor’s CSU budget package. The remaining sections of the brief focus on base support, enrollment, foster youth programs, facility maintenance, and climate‑related capital projects, respectively.

Overview

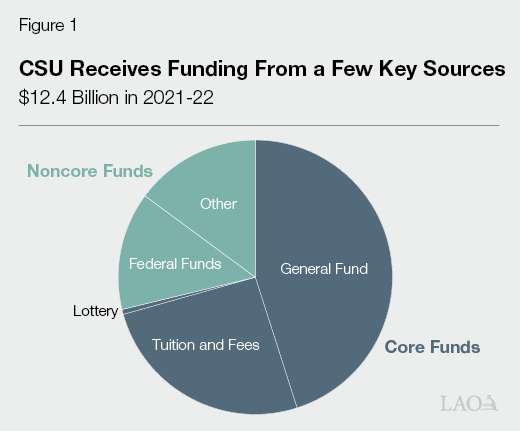

CSU Budget Is $12.4 Billion in 2021‑22. As Figure 1 shows, CSU receives its funding from a few key sources. The Legislature focuses its budget decisions around CSU’s “core funds,” which comprise about 70 percent ($8.8 billion) of CSU’s budget. Core funds at CSU primarily consist of state General Fund and student tuition revenue, with a small portion coming from lottery funds. CSU primarily uses its core funds to support its academic mission of undergraduate and graduate education.

Ongoing Core Funding Increases by $467 Million (6 Percent) Under Governor’s Budget. As Figure 2 shows, nearly all of the increase comes from the General Fund. Ongoing General Fund would increase from $4.6 billion in 2021‑22 to $5.1 billion in 2022‑23, reflecting an increase of $467 million (10 percent). The Governor’s budget assumes revenue from tuition and fees would remain flat. At this time, the CSU Board of Trustees has not adopted any plans to increase tuition charges in 2022‑23. (Although not reflected in the Governor’s budget, the operating budget adopted by the CSU Board of Trustees assumes $43 million in additional tuition revenue from enrollment growth.)

Figure 2

Nearly All of CSU’s Core Fund Increase Comes From General Fund

Ongoing Core Funds (Dollars in Millions)

|

2020‑21 Actual |

2021‑22 Revised |

2022‑23 Proposed |

Change From 2021‑22 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

General Funda |

$4,026 |

$4,597 |

$5,064 |

$467 |

10.2% |

|

Tuition and fees |

3,277 |

3,163 |

3,163 |

— |

— |

|

Lottery |

65 |

73 |

73 |

—b |

—b |

|

Totals |

$7,368 |

$7,833 |

$8,300 |

$467 |

6.0% |

|

FTE studentsc |

412,223 |

397,811 |

407,245 |

9,434 |

2.4% |

|

Funding per student |

$17,874 |

$19,691 |

$20,381 |

$690 |

3.5% |

|

aIncludes funding for pensions and retiree health benefits. b Amount is less than $500,000 or 0.05 percent. cReflects total resident and nonresident enrollment in undergraduate, postbaccalaureate, and graduate programs. |

|||||

|

FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

Governor Has Several CSU General Fund Priorities. As Figure 3 shows, the largest ongoing augmentation is a 5 percent unrestricted base increase. The Governor’s budget also provides ongoing augmentations for retiree health care and pension cost increases, as well as enrollment growth. In addition, the Governor’s budget provides $234 million in one‑time funding for specified initiatives, including deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects, as well as certain climate‑related initiatives.

Figure 3

Governor Proposes New CSU Ongoing

and One‑Time Spending

General Fund Changes in 2022‑23 Over Revised

2021‑22 (In Millions)

|

Ongoing Changes |

|

|

Base augmentation (5 percent) |

$211 |

|

Retiree health benefit cost increase |

82 |

|

Enrollment growth (9,434 FTE students) |

81 |

|

Pension cost increase |

81 |

|

Foster youth programs |

12 |

|

Other adjustments |

—a |

|

Subtotal |

($467) |

|

One‑Time Initiatives |

|

|

Deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects |

$100 |

|

Climate initiatives |

|

|

CSU Bakersfield Energy Innovation Center |

$83 |

|

CSU university farms |

50 |

|

Carryover funds |

1 |

|

Subtotal |

($234) |

|

Total |

$701 |

|

aLess than $500,000. |

|

|

FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|

Governor Announces Multiyear Compact With CSU. In addition to his 2022‑23 budget proposals for CSU, the Governor has indicated his intention to continue providing CSU with 5 percent base increases annually through 2026‑27. He also has indicated his interest in having CSU pursue 22 expectations spanning six priority areas—increasing access for California students, improving student outcomes and equity, making CSU more affordable for students, enhancing intersegmental collaboration, improving workforce alignment, and expanding online education. The administration currently does not intend to codify these expectations. The Department of Finance indicates that the administration could consider proposing smaller future base increases were CSU not to make progress in meeting one or more of these expectations. We describe and assess the Governor’s multiyear compact with CSU, as well as his multiyear agreements with the University of California (UC) and California Community Colleges (CCC), in our publication The 2022‑23 Budget: Overview of Governor’s Higher Education Budget Proposals.

Base Support

In this section, we first provide background on CSU’s operating costs and how CSU generally covers its operating cost increases. Next, we describe the Governor’s proposed base increase for CSU, assess the Governor’s proposal, and make an associated recommendation.

Background

CSU Has Several Core Operating Costs. As with most state agencies, CSU spends the majority of its ongoing core funds (about 75 percent in 2020‑21) on employee compensation, including salaries, employee health benefits, and pensions. Beyond employee compensation, CSU spends its core funds on other annual costs, such as paying debt service on its systemwide bonds, supporting student financial aid programs, and covering other operating expenses and equipment (OE&E). Each year, campuses typically face pressure to increase employee salaries at least at the pace of inflation, with certain other operating costs (such as health care, pension, and utility costs) also tending to rise over time. Though operational spending grows in most years, CSU has pursued certain actions to contain this growth. For example, CSU has pursued certain procurement practices and energy efficiency projects with the aim of slowing associated cost increases.

CSU Has Some Flexibility to Manage Its Operating Costs. In contrast to most state agencies, CSU has authority to negotiate collective bargaining agreements with its unions, as well as to set salary levels for its nonrepresented employees. (About 90 percent of CSU’s permanent employees are represented by a union.) CSU has somewhat less control, however, over the cost of employee benefits. This is because it participates in pension and health care programs administered by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, which makes decisions that, in turn, affect CSU spending in these areas. CSU also faces certain limitations each year related to non‑personnel costs. For example, it generally must pay debt service on the bonds it has issued.

State Has Primarily Supported CSU Operations Through Unrestricted Base Increases. The state and CSU have two main means to cover CSU’s operational cost increases: (1) state General Fund augmentations and (2) additional revenue from tuition increases. Since 2013‑14, the state has provided CSU with base General Fund increases in all years but one. (In 2020‑21, the state reduced General Fund support for CSU to address a projected shortfall in revenues due to the pandemic. The funds were restored the following year.) In most years, the base increases have appeared to be set arbitrarily, without a direct link to CSU’s specific operating cost increases. In addition to these base increases, the state has provided General Fund each year to cover changes in certain CSU pension and retiree health costs. Over the same time period, CSU has increased tuition only once, raising systemwide charges by 4.9 percent for undergraduate and teacher credential students and 6.5 percent for graduate students in 2017‑18.

Proposal

Governor Proposes Unrestricted General Fund Base Increase. The Governor proposes a $211 million (5 percent) unrestricted General Fund increase for CSU in 2022‑23. (As part of his multiyear compact, the Governor proposes to provide 5 percent base increases annually through 2026‑27, with future increases linked with CSU meeting certain expectations.) In addition to the 5 percent base increase, the Governor’s budget would provide a combined $162 million for CSU pension and retiree health cost increases.

Assessment

Base Increases Are Poor Approach to Budgeting for Operating Costs. As we have said in many previous publications, base increases are a poor approach for two reasons. First, they lack transparency. The Governor does not identify how CSU is to use its base increase. Moreover, CSU itself does not adopt a corresponding spending plan until after final budget enactment in June. Second, given the purpose of the funding is unspecified, the amount of proposed augmentations are arbitrary, lacking clear justification based on documented cost increases.

Some Compensation Costs Are Set to Increase in 2022‑23. Each year, CSU faces cost increases related to employee benefits. While the state covers the cost of certain retirement‑related benefits for CSU employees, CSU covers the cost of other benefits, including employee health, from its base funding. For 2022‑23, CSU estimates the cost of providing employee health benefits will increase by $14 million due to rising premiums. In addition, CSU faces costs due to salary increases. CSU recently negotiated a tentative agreement with its largest employee group, the California Faculty Association (CFA), which accounts for about half of its salary pool. The tentative agreement links faculty salary increases in 2022‑23 to the base increase the state provides CSU. If the state provides a base increase between $200 million and $300 million, CFA would receive a 3 percent general salary increase. Were the state to provide a base increase of $300 million or higher, CFA would receive a 4 percent general salary increase. At the Governor’s proposed base increase of $211 million, CSU anticipates that the associated CFA salary provisions cost $86 million. (All cost estimates we cite for increases in the salary pool also include the cost of employer contributions for certain salary‑driven benefits—namely pensions, social security, and Medicare.)

CSU Is Likely to Face Additional Cost Pressures Related to Salary Increases. As of this writing, most of CSU’s nonfaculty employees either have open contracts for 2022‑23 or are non‑represented. CSU estimates the cost of every 1 percent increase in its salary pool for these other employees is approximately $23 million. When deciding how much funding to provide for salary increases in 2022‑23, the Legislature may wish to consider findings from an upcoming study to evaluate CSU’s existing staff salary structure and consider alternative salary models. The state funded this study in the 2021‑22 Budget Act, and the CSU Chancellor’s Office is to report the findings to the Legislature and Department of Finance by April 30, 2022. Additionally, the Legislature may wish to consider the effects of inflation, which is anticipated to be at its highest level in several decades, likely generating pressure for larger‑than‑typical salary increases.

CSU Has Identified Three Other Operating Cost Pressures. These costs consist of a statutory increase in the minimum wage (primarily affecting CSU’s student workers), inflation on OE&E, and the ongoing maintenance of new facilities. Campuses have somewhat limited flexibility to affect these costs. In 2022‑23, CSU estimates that costs in these areas will increase by a total of $40 million.

Recommendation

Build Base Increase Around Identified Operating Cost Increases. We recommend the Legislature decide the level of base increase to provide CSU by considering the operating cost increases it wants to support in 2022‑23. This could include employee health benefits ($14 million), salary increases for employee groups with previously negotiated agreements ($86 million at the Governor’s proposed base funding level), increases in the salary pool for other employee groups (around $23 million for each 1 percent increase), and various other operating costs identified by CSU ($40 million). For illustration, at the Governor’s proposed augmentation level ($211 million), the Legislature could cover benefit cost increases, the previously negotiated salary increases, an approximately 3 percent increase in the salary pool for all other employee groups, and certain other operating costs identified by CSU.

Enrollment

In this section, we first provide background on the state’s approach to funding CSU enrollment, as well as review recent CSU enrollment trends. Next, we describe the Governor’s proposed funding increases for enrollment in 2022‑23 and his proposed multiyear enrollment plan. We then assess the Governor’s proposals and make associated recommendations.

Background

State Typically Sets an Enrollment Target and Provides Associated Funding. In most years, the state sets a systemwide resident enrollment growth target at CSU and provides an associated General Fund augmentation. Augmentations have been determined using an agreed‑upon per‑student funding rate derived from the “marginal cost” formula. This formula estimates the cost to enroll each additional student and shares the cost between anticipated tuition revenue and state General Fund. Whereas the state historically has set CSU enrollment targets for the budget year, two recent budgets have set a target for the year following the budget year. By the time the state budget is enacted in June, campuses have already made the bulk of their admission decisions for the fall term and have little time to plan for additional growth. Moreover, the state largely has lost its ability to influence CSU admission decisions for that year. Setting an outyear target allows the state to send an early signal about enrollment expectations before campuses begin planning and making admission decisions for the following year.

Last Year’s Budget Set Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Target for 2022‑23. In the midst of the pandemic, the Legislature opted not to set enrollment growth targets in the 2020‑21 Budget Act. Such an approach gave CSU flexibility to manage funding reductions and uncertain enrollment demand that year. When state revenues recovered the following year, the state resumed setting enrollment growth targets. Specifically, the state set an expectation in the 2021‑22 Budget Act that CSU grow resident undergraduate enrollment in 2022‑23 by 9,434 full‑time equivalent (FTE) students, relative to the number enrolled in 2021‑22.

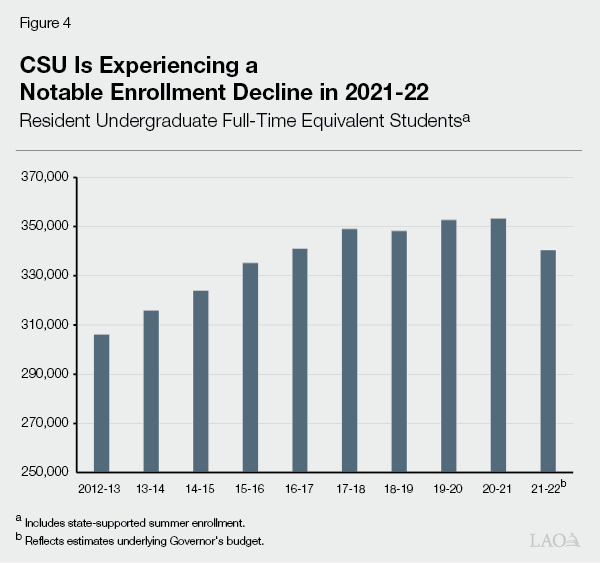

Enrollment in 2021‑22 Has Dropped Notably. As Figure 4 shows, CSU resident undergraduate enrollment has generally increased over the past decade, peaking at about 353,000 FTE students in 2020‑21. In 2021‑22, however, enrollment is declining. Though final 2021‑22 enrollment data are not yet available, the Governor’s budget reflects CSU’s initial estimates. Based on these estimates, resident undergraduate enrollment falls to about 340,000 FTE students in 2021‑22—nearly 13,000 (3.6 percent) fewer students than in the previous year. CSU attributes this decline to the effects of the pandemic, which led to fewer applications from entering freshmen, as well as a smaller pipeline of transfer students due to enrollment declines at CCC.

Proposals

Governor Proposes to Fund Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Growth in 2022‑23. In accordance with the expectation set in the 2021‑22 Budget Act, the Governor’s budget provides $81 million for CSU to grow resident undergraduate enrollment by 9,434 FTE resident undergraduate students in 2022‑23 over the 2021‑22 level. The amount assumes that the General Fund share of the marginal cost per student is $8,586 (the estimated 2021‑22 rate—the rate available at the time of budget enactment).

Governor Proposes 2023‑24 Growth as Part of Multiyear Enrollment Plan. The Governor’s compact includes a multiyear plan for CSU to grow resident undergraduate enrollment by around 1 percent each year from 2023‑24 through 2026‑27. Though proposed as part of the compact, the Governor does not specify the 1 percent growth expectation for 2023‑24 in the budget bill. According to the administration, this annual growth would represent more than 14,000 additional FTE students across the four‑year period. Under the Governor’s compact, CSU would not receive additional funds for enrollment growth over the period, but instead it would need to accommodate the higher costs from within its base increases.

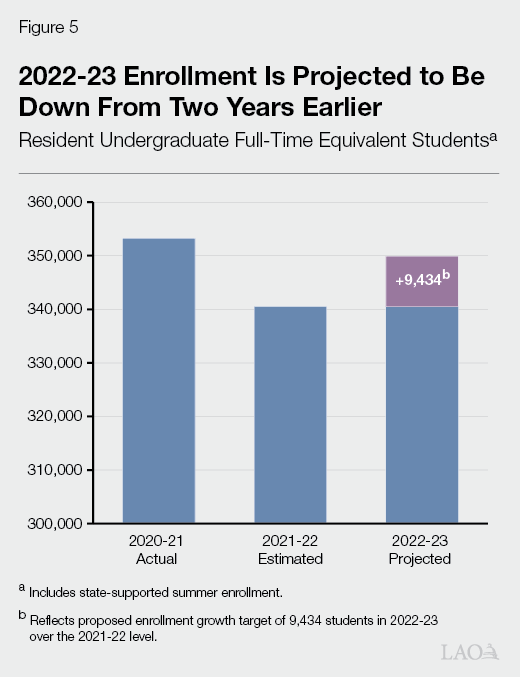

Assessment

Recent Enrollment Decline Is Cause for Revisiting 2022‑23 Expectation. As Figure 5 shows, the notable enrollment decline in 2021‑22 affects CSU’s 2022‑23 enrollment level in an important way. Even after adding the proposed 9,434 FTE students, the projected resident undergraduate enrollment level in 2022‑23 is 3,358 FTE students lower than the actual enrollment level two years earlier in 2020‑21. Under the Governor’s budget, the state would in effect be providing more funding for CSU even though it would enroll fewer students. We think this likely runs counter to the Legislature’s intent to expand access and fund greater enrollment.

Legislature Could Still Influence 2023‑24 Enrollment. As CSU already is in the midst of making admission decisions for 2022‑23, the Legislature has limited ability at this point to influence CSU’s 2022‑23 enrollment level. The Legislature could, however, send an early signal to campuses about its enrollment expectations for 2023‑24. In setting an enrollment target for 2023‑24, the Legislature could consider the trends described below.

- High School Graduates. The Department of Finance projects the number of high school graduates in California to increase by 0.6 percent in 2022‑23. All else equal, an increase in high school graduates in 2022‑23 would increase CSU freshman enrollment demand in 2023‑24.

- Freshman Applications. CSU reports a large increase in freshman applications for the fall 2022 term (up 13 percent from the fall 2021 term), as of mid‑January. Such an increase could signal a rebound in freshman demand from a depressed pandemic enrollment level. Whether freshman applications will remain elevated for 2023‑24 is uncertain.

- Community College Students. CCC enrollment declined in 2020‑21, and a further drop is expected in 2021‑22. Correspondingly, CSU reports a 9.6 percent decline in new transfer students in fall 2021, and an even steeper (14 percent) decline to date in transfer applications for fall 2022. It is uncertain whether transfer enrollment demand will recover by 2023‑24.

- Continuing Cohorts. In fall 2021, the number of new resident undergraduates entering CSU was 6.8 percent lower than in the previous fall. This smaller new cohort will remain at CSU for the next few years, potentially leading to fewer continuing students in 2023‑24.

The collective impact of these demographic, application, and cohort trends on CSU enrollment in 2023‑24 is uncertain. Though we think notable growth in CSU enrollment demand is unlikely, some growth is possible. That said, the pandemic continues to make enrollment projections unusually challenging.

Some Eligible Applicants Are Not Getting Into Their Campus of Choice. Because some CSU campuses and programs are “impacted” (meaning they have more student demand than available slots), some applicants meeting CSU’s minimum systemwide eligibility requirements are not accepted at any campus to which they apply. Since fall 2019, CSU has been redirecting these applicants to nonimpacted campuses. In fall 2020 (the most recent data publicly available), CSU redirected 14,848 eligible applicants, of whom only 728 (5 percent) went on to enroll at a CSU campus. Providing more enrollment funding to CSU could potentially increase the number of students who can enroll at their campus of choice.

Eligibility and Admission Policies Remain a Consideration. Historically, the state has expected CSU to draw its freshman admits from the top one‑third of the state’s high school graduates. As we have noted in previous analyses, CSU has been found to be drawing from beyond these pools in recent years, and it likely continues to do so. In past periods, the state has expected the universities to tighten freshman admission policies when they were found to be drawing from beyond these pools. When CSU tightens its admission policies, it effectively redirects a portion of its enrollment to CCC (which is likely to have capacity for additional students, given the enrollment decreases it has experienced during the pandemic).

Recommendations

Legislature Could Reconsider 2022‑23 Funding. When the Legislature set the 2022‑23 enrollment target last June, it likely did not anticipate the notable enrollment decline in 2021‑22. If CSU were to grow 9,434 additional students in 2022‑23 from the depressed current‑year level, it still would be serving about 3,000 fewer students than it did in 2020‑21. In light of the updated enrollment data, the Legislature may wish to reconsider providing CSU any enrollment growth funding in 2022‑23.

Recommend Setting Enrollment Target for 2023‑24. We recommend the Legislature set a target enrollment level for 2023‑24 in the 2022‑23 Budget Act. (As we discuss in The 2022‑23 Budget: Analysis of Major UC Proposals, specifying a target total enrollment level provides greater clarity and accountability than setting only an incremental growth target.) Given the concerns raised in the previous section about unrestricted base increases, we recommend providing enrollment growth funding to cover the associated cost rather than having CSU accommodate the cost from within its base funding. We estimate that every 1 percent growth in resident undergraduate enrollment in 2023‑24 would add about 3,500 FTE students, at a General Fund cost of around $35 million. We recommend scheduling any funds for growth in 2023‑24 to be appropriated in the 2023‑24 budget, as this approach allows the state more easily to align funding with updated enrollment estimates for that year.

Foster Youth Programs

In this section, we provide background on CSU’s existing foster youth programs, describe the Governor’s proposal to increase foster youth support at CSU, assess the proposal, and offer an associated recommendation.

Background

Notable Disparities Exist for Foster Youth. National data indicate foster youth enrolling in higher education are less likely to complete a bachelor’s degree than their peers. The available data indicate foster youth in California also tend to have lower graduation rates. Though CSU does not track the graduation rates of its foster youth students, UC reports that foster youth who entered UC as freshmen in fall 2012 or fall 2013 had a six‑year graduation rate of 68 percent, compared to 84 percent for their non‑foster youth peers. Similarly, foster youth who entered UC as transfer students from fall 2012 through fall 2015 had a four‑year graduation rate of 80 percent, compared to 88 percent for their peers. In addition to academic differences, research shows that foster youth students face other disparities. Based on a 2018 CSU study, 63 percent of foster youth attending CSU reported experiencing food insecurity, compared to 42 percent of all CSU students. In addition, 25 percent of foster youth reported being homeless at least once in the past 12 months, compared to 11 percent of all students.

Nearly All CSU Campuses Currently Have Foster Youth Programs. Of CSU’s 23 campuses, 21 currently have a foster youth program, and an additional campus is actively developing one. (The remaining campus, Maritime, enrolls fewer than 1,000 total students.) These foster youth programs go by various names, including Guardian Scholars, Renaissance Scholars, and Promoting Achievement Through Hope. The specific services provided by these programs vary by campus but commonly include academic and career advising, financial assistance, workshops, and social events. (In addition, all CSU campuses are required under state law to support current and former foster youth in several other ways, including by providing tuition waivers, priority registration for courses, and priority for on‑campus housing.) CSU indicates that about 1,300 current and former foster youth, out of an estimated 2,700 current and former foster youth enrolled across the system, currently are participating in campus foster youth programs.

CSU’s Programs Rely Partly on External, Partly on State Support. Comprehensive spending data on foster youth support services across all CSU campuses is not available. However, CSU reports that 12 campuses are spending a combined $3.4 million annually on their foster youth programs. More than half of this funding comes from external sources such as grants and donations, with the remainder coming primarily from the state (through base funding and certain student support programs).

Other Programs Also Provide Financial Assistance to Foster Youth. The California Student Aid Commission administers the Chafee Educational and Training Vouchers Program, a federal program that provides grants of up to $5,000 annually to students who were in foster care between the ages of 16 and 18. The Governor’s budget includes $17 million (primarily in federal funds) for the Chafee program in 2022‑23 to provide awards to about 3,500 students across all higher education segments. In addition, foster youth receive support through Cal Grants, the state’s main financial aid program. State law provides foster youth with expanded eligibility for Cal Grants, including by setting a higher age limit, a later application deadline, and a longer award duration. The Cal Grant program typically covers tuition for financially needy students at CSU. The 2021‑22 budget also increased the Cal Grant access award (which is intended to cover nontuition expenses such as food and housing) to $6,000 for current and former foster youth, compared to $1,648 for most other low‑income students.

Proposal

Governor Proposes Funding for Foster Youth Support. The Governor proposes $12 million ongoing to CSU for this purpose. Under the proposed trailer bill language, the Chancellor’s Office would develop a formula to allocate the funds to campuses offering foster youth programs. (The proposed funding level assumes each campus would receive a base allocation of between $75,000 and $150,000 depending on its program size, in addition to $4,250 per participant. The administration estimates the program would serve a total of approximately 2,200 participants.) Campuses could use their funds for a broad range of foster youth services, including outreach, service coordination, academic advising, career guidance, health and mental health service referrals, and financial assistance. (These are largely the same services that state law directs participating community colleges to provide under the NextUp foster youth program, reflecting the administration’s intent to align foster youth support services across segments. The Governor has a similar proposal for UC.) The trailer bill language indicates that services provided under the proposal are intended to supplement and not supplant existing foster youth services provided by the campus, county, or state. The language also requires CSU to submit a report on foster youth services and outcomes every two years beginning March 31, 2024.

Assessment

Additional Support for Foster Youth Could Be Warranted. Providing additional support targeted for foster youth could help address their academic disparities as well as their higher rates of food and housing insecurity. It also would align with the Legislature’s broader interest in addressing equity gaps at CSU.

Proposed Program Structure and Reporting Requirements Have Merit. Because the proposed trailer bill language offers campuses flexibility to determine how the funds are used, campuses could integrate the funds with their existing foster youth programs. Given that these programs currently rely heavily on external funding, ongoing state funding could allow for greater stability in services from year to year, as well as greater capacity to expand services and potentially support more students. In addition, the proposed reporting requirement would enable the Legislature to monitor program outcomes. Specifically, the recurring report would provide information on the foster youth services provided by CSU campuses; detail on the use of the proposed state funds and any other funds for foster youth services; and enrollment, retention, and completion rates for foster youth by campus.

Recommendation

Consider Proposal Among Ongoing Spending Priorities. Given the proposal addresses a documented problem, aligns well with existing foster youth programs, and contains provisions for legislative oversight, the Legislature has clear reasons to adopt the Governor’s proposed augmentation. The Legislature, however, may wish to weigh this proposal against its other ongoing spending priorities for CSU. The Legislature, for example, could consider using the $12 million to bolster core ongoing operations at CSU, as helping CSU recruit and retain staff can promote overall program quality. (In the “Base Increase” section of this brief, we highlight the salary pressures CSU is facing, particularly in light of high inflation.) Another option would be to use the $12 million for other existing student support programs at CSU, including the Graduation Initiative, which is intended to improve student outcomes and close equity gaps across all student groups.

Facility Maintenance

In this section, we provide background on CSU’s maintenance backlog, describe the Governor’s proposal to fund deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects at CSU, assess the proposal, and offer associated recommendations. Throughout this section, we use “facility maintenance” broadly to encompass activities needed to keep academic facilities and infrastructure in good condition. This includes capital renewal projects to replace aging building components, such as roofs and heating and ventilation systems.

Background

Campuses Have Maintenance Backlogs. Like most state agencies, CSU campuses are responsible for funding the maintenance and operations of their buildings from their support budgets. When campuses do not set aside enough funding from their support budgets to maintain their facilities, they begin accumulating backlogs. These backlogs can build up over time, especially during recessions when campuses sometimes defer maintenance projects as a way to help them cope with state funding reductions.

CSU Has Developed Estimates of Its Facility Maintenance Needs. To help guide future state funding decisions, the Legislature in the Supplemental Report of the 2019‑20 Budget Act directed CSU to develop a long‑term plan to quantify and address its maintenance and capital renewal backlog. In response, CSU submitted a report quantifying its facility maintenance needs to the Legislature in January 2021. It also provided an updated estimate of its maintenance needs as part of the multiyear capital outlay plan it submitted to the Legislature in December 2021. Based on those updated estimates, CSU reports having a total ten‑year capital renewal need of $2.8 billion, on top of an existing $5.8 billion maintenance backlog. (This estimate of the backlog does not reflect projects that have been funded but not yet completed.) As Figure 6 shows, CSU estimates it would need to spend an average of $284 million annually over the next ten years to address its capital renewal needs and prevent its backlog from growing, as well as an additional $584 million annually to eliminate its existing backlog. The combined amount is $686 million more than the best available estimate of CSU’s current annual spending on these types of projects ($182 million).

Figure 6

CSU Reports Considerable

Maintenance and Capital Renewal

Needs

(In Millions)

|

Total Costs |

|

|

Projected ten‑year renewal need |

$2,842 |

|

Existing maintenance backloga |

5,838 |

|

Total |

$8,679 |

|

Average Annual Costb |

|

|

Capital renewal costs |

$284 |

|

Existing maintenance backlog |

584 |

|

Total |

$868 |

|

Existing Annual Spendingc |

$182 |

|

Gap in Annual Spending |

$686 |

|

aDoes not reflect projects that have been funded but not yet completed. bReflects estimates of amounts CSU would need to spend each year for ten years to prevent its backlog from growing while also eliminating the existing backlog. cReflects average annual operating expenditures on major repairs and renovations from 2017‑18 through 2019‑20. |

|

State Has Provided Funds to Address Backlogs. In the years since the Great Recession, the state has provided one‑time funding to CSU to help campuses address their maintenance backlogs. Figure 7 shows the amount appropriated by the state for deferred maintenance and related purposes each year from 2015‑16 through 2021‑22. Funding over the period totals $659 million, with about half of that amount provided in 2021‑22. Notably, the state allowed CSU to use its 2021‑22 allocation to pay for either deferred maintenance or energy efficiency projects. CSU reports that it is spending about 80 percent of the allocation on deferred maintenance projects (some of which also have an energy efficiency component), and the remaining 20 percent on projects strictly intended to improve energy efficiency.

Figure 7

State Has Provided Funding to Address Deferred Maintenance at CSU

One‑Time Funds (In Millions)

|

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

|

|

General Fund |

$25 |

$35 |

— |

$35 |

$239a,b |

— |

$325c |

|

aThe 2020‑21 budget package allowed CSU to repurpose unspent 2019‑20 deferred maintenance funds for other operational purposes. bAmount was provided for deferred maintenance or campus‑based child care facilities. cAmount was provided for deferred maintenance or energy efficiency projects. |

|||||||

Proposal

Governor Proposes Funding for Deferred Maintenance and Energy Efficiency Projects. The Governor proposes to provide $100 million one‑time General Fund to CSU for these purposes. CSU indicates the distribution of funds between deferred maintenance and energy efficiency projects likely would be similar to last year. CSU indicates it would likely allocate the funds among the campuses based on factors such as the age and square footage of their facilities, as well as their amount of deferred maintenance need. Campuses would have discretion to choose specific projects. CSU has submitted to our office a list of potential projects identified by the campuses, with costs totaling $1 billion. Budget bill language would direct the administration to report to the Legislature on the specific projects selected within 30 days after the funds are released to CSU.

Assessment

Proposal Reflects a Prudent Use of One‑Time Funding. Providing funds for deferred maintenance projects would address an existing need that is growing. Addressing this need can help avoid more expensive facilities projects, including emergency repairs, in the long run. Funding energy efficiency projects also could be beneficial, as these projects are intended to reduce campuses’ utility costs over time.

One‑Time Funding Does Not Address Underlying Cause of Backlog. Deferred maintenance backlogs tend to emerge when campuses do not consistently maintain their facilities and infrastructure on an ongoing basis. Based on its estimates, CSU would need to increase its ongoing spending on maintenance and capital renewal by more than $100 million just to keep the backlog from growing. (This reflects the gap between CSU’s average annual capital renewal costs of $284 million and its existing annual spending of $182 million.) Although one‑time funding can help reduce the backlog in the short term, it does not address the underlying ongoing problem of underfunding in this area.

Recommendations

Consider Governor’s Proposal as a Starting Point. To address CSU’s maintenance backlog, we recommend the Legislature provide at least the $100 million proposed by the Governor. As it deliberates on the Governor’s other one‑time proposals and receives updated revenue information in May, the Legislature could consider providing CSU with more one‑time funding for this purpose. (Though we focus on CSU in this budget brief, other state agencies also have deferred maintenance backlogs. The Legislature could consider providing one‑time funding to address these backlogs too, particularly as the Governor has not proposed funding to most other agencies for this purpose in 2022‑23.)

Consider Developing Strategy to Address Ongoing Maintenance and Capital Renewal Needs. In addition to providing one‑time funding for deferred maintenance, we encourage the Legislature to begin developing a long‑term strategy around university maintenance and capital renewal needs. Potential issues to consider include timing, fund sources, ongoing versus one‑time funds, and reporting. Given the magnitude of the ongoing maintenance and capital renewal needs at the universities, developing such a strategy would likely require significant planning beyond the 2022‑23 budget cycle.

Climate‑Related Capital Projects

In this section, we provide background on capital outlay planning and financing at CSU, describe the Governor’s proposals to fund certain CSU capital projects related to climate change, assess those proposals, and offer associated recommendations. (The Governor’s budget includes many climate‑related proposals, spanning a wide range of policy areas including the environment, transportation, housing, workforce development, and education.)

Background

CSU Has a Multiyear Capital Outlay Plan. Under state law, CSU submits a capital outlay plan annually to the Legislature by November 30. The plan includes a list of projects proposed for each campus over the next five years, as well as the associated costs. The most recent plan identifies $16.4 billion in academic facility projects (and $7 billion in self‑supported projects) proposed for 2022‑23 through 2026‑27. For 2022‑23, the plan identifies 23 priority academic facility projects costing a total of $3.1 billion. CSU primarily finances its academic facility projects through university bonds, paying the associated debt service from its General Fund support appropriation. At times (including most recently in the 2021‑22 Budget Act), the state has also provided one‑time General Fund to support specific CSU capital outlay projects on a pay‑as‑you‑go basis.

Proposals

Governor Proposes to Construct Energy Innovation Center at CSU Bakersfield. The Governor’s budget provides $83 million one‑time General Fund for the proposed building. The Governor’s Budget Summary indicates that this proposal supports climate change research. In conversations with our office, the administration has further specified that the building would allow for research and development on carbon management and clean energy issues, in collaboration with the Kern County energy sector, among other potential collaborators.

Governor Proposes Funding Equipment and Facilities at University Farms. Four CSU campuses (Chico, Fresno, Pomona, and San Luis Obispo) operate university farms to support instruction and research in their agriculture programs. The Governor’s budget provides $50 million one‑time General Fund for these university farms to acquire equipment and construct or modernize their facilities. Provisional language indicates the funds are “to support program efforts to address climate‑smart agriculture and other climate‑related issues.”

Assessment

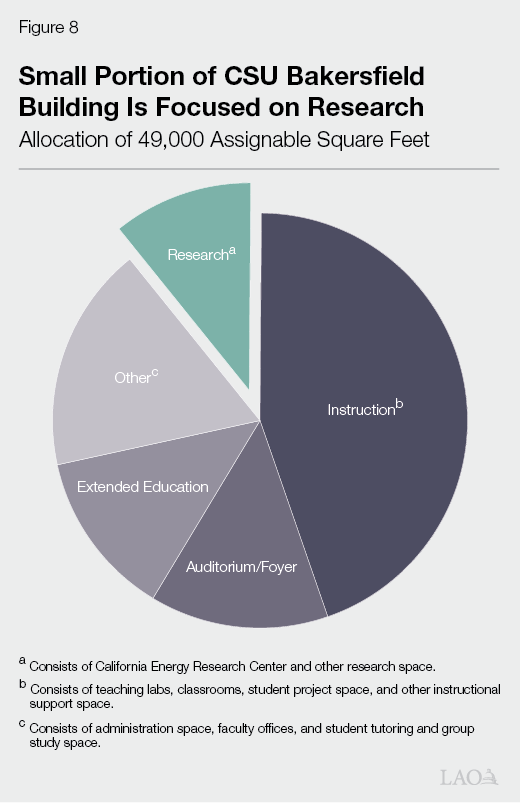

Climate‑Related Research Space Is a Small Element of Proposed CSU Bakersfield Building. Although the building would include space for research on climate‑related issues, research is only a small portion of the project proposal. Based on project data from CSU, research space accounts for only about 10 percent of the assignable space within the proposed building. As Figure 8 shows, the largest component of the building is instructional space, primarily consisting of teaching labs for the engineering, physics, and computer science programs. Other building components include a 240‑seat auditorium, faculty offices, and student study space. That is, the bulk of the proposed funding would likely go to typical academic facility costs, without a direct nexus to climate innovation. In addition, 13 percent of the assignable space within the proposed building is for the campus’s extended education programs—a self‑supported enterprise that typically would be expected to fund its own facility projects.

Climate Benefits of University Farms Proposal Are Likely Minor. Similar to the CSU Bakersfield proposal, the university farms proposal primarily would support capital improvements for certain academic programs—in this case, agriculture programs at four CSU campuses. CSU has submitted a list of 14 projects that the four campuses would pursue with the proposed funds. The list includes some projects with climate‑related objectives, such as replacing older farm vehicles with electric vehicles and upgrading irrigation systems to conserve water. However, the climate‑related objectives are less clear for other proposed projects, such as adding space to a meat lab, replacing a beekeeping lab, and modernizing horticulture facilities. On the whole, it is uncertain whether the climate benefits of the proposed university farm projects would exceed the climate benefits of other capital projects that CSU routinely undertakes—including the energy efficiency projects discussed in the previous section.

Other CSU Capital Outlay Priorities Outrank Governor’s Proposals. CSU’s 2022‑23 capital outlay priority list does not include any projects at the university farms, suggesting other capital needs are likely of greater urgency systemwide. Although the CSU Bakersfield building does appear on CSU’s priority list, it ranks 11th out of the 23 projects. The ten projects ranked above it include infrastructure improvements across the 23 campuses, as well as four projects to address seismic deficiencies at specific campuses. We think it is reasonable to prioritize these projects over the Bakersfield project, given that they address issues relating to life safety and the continuation of existing campus operations. If the Legislature wishes to add space for engineering programs as the Governor is proposing, CSU’s top ten priorities also include two other such projects—at the San Marcos and Sacramento campuses. We think these latter two projects have stronger justification than the Bakersfield project, as the San Marcos and Sacramento campuses utilize their existing teaching lab and classroom space at notably higher rates than the Bakersfield campus. Moreover, the engineering program at the San Marcos campus is impacted (meaning it cannot accommodate existing enrollment demand).

Recommendations

Consider Proposals a Lower Spending Priority. We do not see a strong rationale for prioritizing either the CSU Bakersfield Energy Innovation Center or the university farm equipment and facility improvements. Based on our assessment, neither proposal is likely to have major climate benefits, and neither reflects the highest capital outlay priorities at CSU. The Legislature could consider redirecting the proposed funds to other capital purposes. (Because both of the Governor’s proposals are excludable from the state appropriations limit, the Legislature very likely would need to use the associated funds for excludable purposes.) This could include capital improvements at CSU, such as addressing its maintenance backlog (described in the previous section) or funding higher‑priority academic facility projects. Alternately, it could include capital purposes elsewhere in the budget that have a clearer focus on climate change research and development, such as the Governor’s proposed industrial decarbonization program at the California Energy Commission. (We plan to provide our assessment of the proposed industrial decarbonization program in an upcoming brief.)