LAO Contact

March 30, 2022

The 2022‑23 Budget

State Appropriations Limit Implications

- Governor’s Budget Likely Unsustainable

- How Can the Legislature Respond in the Short Term?

- How Can the Legislature Respond in the Long Term?

- Technical Appendix

Summary

SAL Will Constrain the Legislature’s Choices This Year; State Likely to Face Challenges Balancing the Budget in the Next Couple Years. Based on recent tax revenue collection data, the state will face a significant state appropriations limit (SAL) requirement—possibly in the tens of billions of dollars—at the time of the May Revision. The Legislature and Governor can address that requirement with tax reductions and/or with more spending on specific purposes, such as capital outlay. This year, the surplus likely will be large enough to cover those requirements. In future years, however, it is very unlikely this would be the case, requiring the Legislature to make reductions to existing spending. Under our estimates, this could happen as soon as next year.

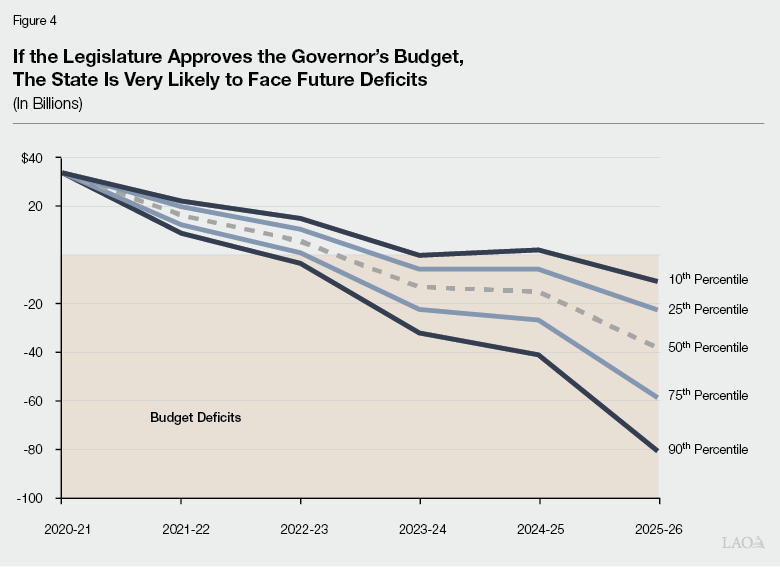

Under the Governor’s Budget, the State Is Very Likely to Face Future, Serious Budget Challenges. If the Legislature adopts the Governor’s budget proposals and the economy continues to grow, the state would not have surpluses large enough to pay for large and growing SAL requirements in future years. If the economy does not continue to grow, the state would face budget problems due to revenue shortfalls. For this analysis we examined 10,000 possible revenue and economic scenarios. In over 95 percent of scenarios, the state faces a budget problem by 2025‑26 either due to constitutional spending requirements or a recession. In these scenarios, the state would need to make cuts to existing services to bring the budget back into balance.

Options for Avoiding Budget Problems in Future Years. The Legislature has options to avoid budget problems from arising over the next few years. For example, the Legislature can delay paying SAL requirements (for up to two years), change the definition of subventions, and/or reject nearly $10 billion in Governor’s budget proposals and save those funds to meet future SAL requirements. In fact, we recommend all, or nearly all, of the Governor’s budget proposals that do not help the state meet SAL requirements be rejected. However, all of these options are short‑term remedies, not long‑term solutions. Over the long term, as long as the economy continues to grow, the Legislature has two choices: (1) reduce taxes in order to slow revenue growth or (2) request the voters change the SAL.

Governor’s Budget Likely Unsustainable

A budget problem occurs when state spending under current law exceeds state resources available. Because the state must pass a balanced budget, when a budget problem occurs, the Legislature must take actions to bring the budget into balance, like cutting spending or raising revenues. Budget problems most commonly occur during recessions. Now, however, we have determined that future budget problems are likely to occur whether revenues grow slower, faster, or as expected. The remainder of this section explains these dynamics assuming the Governor’s budget proposals are adopted.

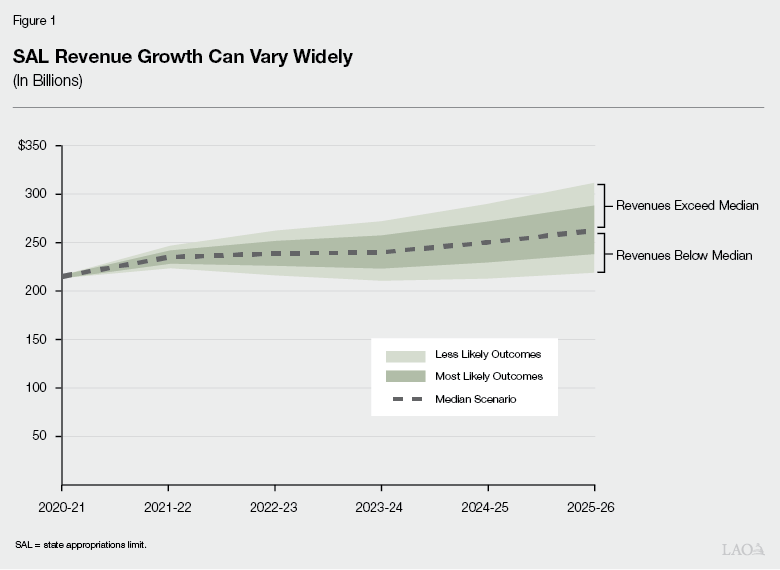

Revenue Growth Can Vary Widely. The budget is based on a projection of revenues. Our projections aim to represent the median revenue outcome—in which there is an equal chance that actual revenue collections fall above or below our projection. However, revenues could differ substantially from this median (dotted line in Figure 1)—either higher or lower. Figure 1 shows the range of likely outcomes. The most likely outcomes are shown in the darker shaded area. Less likely outcomes are shown in the lighter shaded region. Some scenarios outside these shaded areas also are possible, but would be outcomes associated with major unforeseen events that dramatically shift the state’s economic situation.

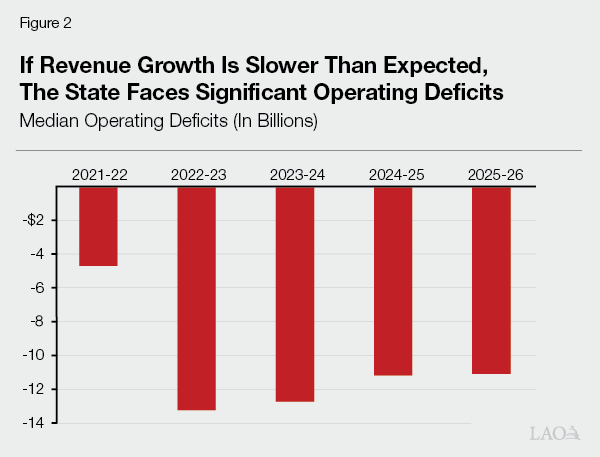

If Revenue Growth Falls Below Median, State Likely to Have a Budget Problem. Because the state usually plans to spend all or nearly all of its forecasted revenues, the state typically faces a budget problem if revenues grow slower than expected. Figure 2 shows the size of annual budget problems under an average recession (assuming the Legislature adopted the Governor’s budget).

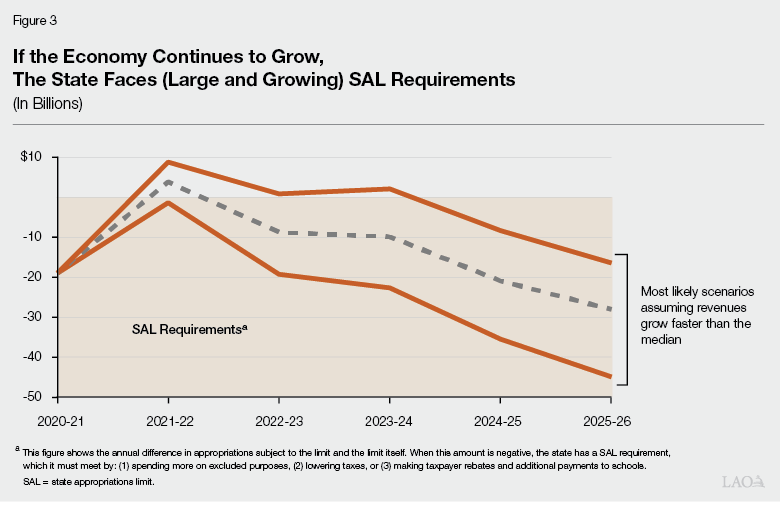

If Revenue Growth at or Above Median, SAL Requirements Grow Significantly... In contrast, if revenues grow at or above the median, the state would have growing state appropriations limit (SAL) requirements. As described in more detail in other publications (see The State Appropriations Limit), the SAL restricts the use of revenue above a certain threshold. We refer to the restrictions on the use of those revenues as SAL requirements. (See the nearby box for more information on key terms and concepts used in this report, including how SAL requirements work.) As Figure 3 shows, if revenues grow faster than the median (as shown in figure 1) the state is very likely to face large—and growing—SAL requirements, reaching somewhere between $20 billion and $45 billion by 2025‑26. (Note that these scenarios assume the state addresses the 2021‑22 SAL requirement. That is, the estimates already assume the state takes some action similar to the various tax rebate proposals introduced by the Legislature and Governor in recent weeks.)

Key Terms and Concepts in This Report

State Appropriations Limit (SAL) Requirements. Amounts the state is required to allocate to meet its constitutional requirements under Proposition 4 (1979). In short, a SAL requirement arises when the state’s appropriations subject to the limit are expected to exceed the limit itself. The Legislature can meet SAL requirements in one of three key ways: (1) lowering proceeds of taxes (for example, by providing taxpayer rebates), (2) spending more on excluded purposes (for example capital outlay or money to local governments), or (3) issuing taxpayer rebates and providing more funding to schools and community colleges.

How Does the State Pay for SAL Requirements? This brief assumes that the Legislature uses General Fund discretionary funds to meet its SAL requirements. That is, we assume the state: (1) meets all of its commitments under current law and policy, including its constitutional requirements; (2) pays for the Governor’s budget proposals; and (3) uses General Fund monies to pay for any SAL requirements that arise as a result of the calculation described above. If the state’s General Fund resources are insufficient to cover these three categories of costs, the result is a budget deficit.

Proposals That Do Not Meet a SAL Requirement. Any budget proposals that do not meet one of the three categories listed in the first paragraph do not help the state meet its SAL requirements. This includes, for example, most spending on program benefits, such as for health and human services programs; required or voluntary contributions to the state’s retirement systems; and deposits into the state’s reserves.

The SAL and Budget Surpluses. The state has a surplus when spending under current law is lower than resources available in a single year. SAL requirements can exist in tandem with a surplus, but need not. For example, the state can have a surplus that is larger than its SAL requirements (as it likely will this year) or smaller than its SAL requirements (as is the case for many of the scenarios shown in this brief). In fact, the state can even have a SAL requirement and no surplus at all. That is because these calculations are wholly separate—the availability of a surplus depends on how much the state has committed to spending over time, while SAL requirements exist because revenues exceed a limit established by voters in 1979.

…As Do Budget Problems. For each dollar of General Fund revenue, the state is required to provide a certain amount to schools and community colleges and a certain amount to reserves and debt payments. Once tax revenues reach the appropriations limit, the state not only faces a dollar‑for‑dollar SAL requirement, but also continues to be required to spend a portion of each General Fund dollar on schools and community colleges and reserves and debt payments. As a result, for each dollar collected once the state reaches the appropriations limit, the state faces roughly $1.60 in constitutional requirements. (We describe this dynamic in more detail in our post The 2022‑23 Budget: Initial Comments on the State Appropriations Limit Proposal.) Consequently, if revenues grow at or above the median, constitutional spending requirements would grow faster than available resources, causing potentially significant budget problems. In this scenario, the state would be required to cut non‑constitutionally required spending to solve the budget problems.

Regardless of Revenue Growth, Future Budget Problems Are Very Likely Under the Governor’s Budget. As a result of these two dynamics—either slower revenue growth resulting in operating deficits or faster revenue growth resulting in larger constitutional spending requirements—the budget is very likely to face budget problems in the coming years. Figure 4 shows the range of likely budget problems assuming the Legislature approved all of the Governor’s budget proposals. As the figure shows, the state most likely would face budget deficits ranging from $5 billion to $20 billion as soon as next fiscal year regardless of revenue growth. By 2025‑26, those deficits would most likely grow to $20 billion to $60 billion.

The State Cannot “Grow Its Way Out” of Budget Problems. Higher revenues do not increase the state’s ability to meet SAL requirements. In fact, the opposite is true. As described above, because of the state’s constitutional spending requirements—including that the SAL requires the state to dedicate all revenues above a certain threshold for SAL requirements, no matter how much revenues grow—higher revenue growth means each $1 collected results in $1.60 of spending requirements. This dynamic puts the state in an untenable fiscal situation.

How Can the Legislature Respond in the Short Term?

While the budget could face problems either as a result of a recession or continued economic growth—both on the upside and downside—this post focuses on the steps the Legislature can take to mitigate the budget’s upside risk. That is, how the Legislature can promote the chances that budget stays balanced if revenues come in at or above expectations. This section outlines three steps the Legislature can take to mitigate risks in the short term.

Reject a Significant Share of the Governor’s Budget Proposals

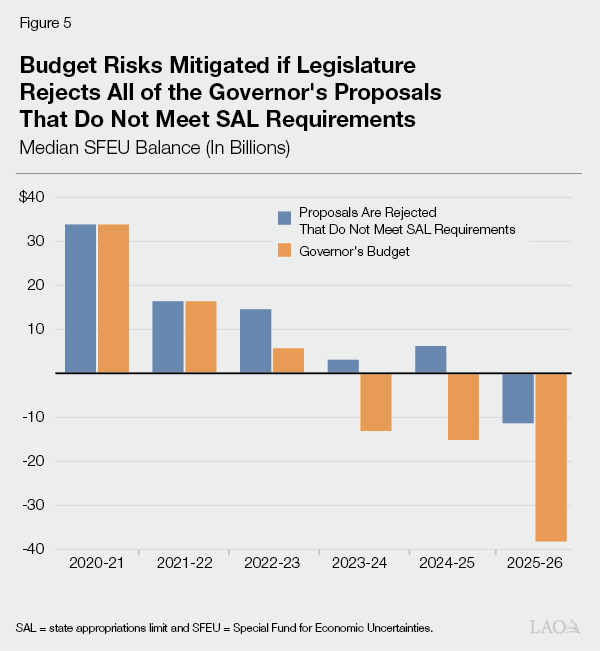

Reject All of the Governor’s Proposals That Do Not Meet a SAL Requirement… The Legislature can forestall budget deficits for a few years by rejecting all of the nearly $10 billion in Governor’s budget proposals that do not meet a SAL requirement and then saving those funds in order to meet future SAL requirements. (The Governor’s proposals that meet SAL requirements could be adopted. However, the Legislature could adopt alternative proposals as long as they meet the SAL requirements.) Figure 5 shows how this action would change the budget outlook. As the figure shows, under the Governor’s budget policies (orange bars), the state is most likely to face large and growing budget deficits as soon as 2023‑24. If the Governor’s budget proposals that do not meet a SAL requirement are rejected (and those funds are saved instead [blue bars]), the state can most likely delay those deficits until 2025‑26. (We list the Governor’s budget discretionary spending proposals that do not help the state meet its SAL requirements in our post The 2022‑23 Budget: Initial Comments on the State Appropriations Limit Proposal. We also describe this concept—proposals that do not meet a SAL requirement—in the box above.) Consequently, we recommend rejecting these proposals.

…And Save Funds to Meet Future SAL Requirements. The scenario shown in Figure 5 assumes the state saves $10 billion in 2022‑23 and then uses those funds to pay for SAL requirements in 2023‑24 and/or 2024‑25. As such, the nearly $10 billion in funds available as a result of rejecting these proposals must be saved to help balance the budget in the future. That is because, in the coming years, the state is likely to face large SAL requirements without a surplus large enough to pay for them. (The box above also described the relationship between the surplus and SAL requirements.) The Legislature would not get the same benefit if it rejects these proposals and then spends the funds on excluded purposes because such an action would not help it meet these future requirements.

Delay SAL‑Required Payments

State Also Can Ease Some Short‑Term Pressure by Pushing Out Payments… Another way the state can manage this risk in the short term is by delaying when SAL requirements are paid. Under the Constitution, when state revenues exceed the limit over two years, the Legislature has an additional two years to return the excess to taxpayers and make additional payments to schools. Delaying these payments can ease some of the short‑term pressure because the state has an additional year or two of revenue growth—and therefore more resources available—to meet the requirements.

…But the State Must Set Aside Funds for Future Requirements or Risk Very Severe Budget Deficits. However, if the Legislature chooses to continuously delay making these payments, but does not set aside as much as it can to pay for those requirements in the future, it eventually will face the worst‑case scenario: a future, unfinanced SAL requirement coupled with a recession. Consequently, delaying action on the current‑year requirement without setting aside funds to meet the requirement in future years would be unwise.

Change the Definition of Subvention

The Legislature Also Could Change the Definition of Subvention. Another way to address this issue in the short term is to change the definition of subvention. Under the Constitution and statute, subventions—funding provided to local governments on an unrestricted basis—meet SAL requirements and are counted, instead, at the local level. The state could amend the definition of subvention in order to count more funding provided at the local level. For example, instead of specifying that only unrestricted funds provided to local governments should count as subventions, statute could state that any funds provided to local government count as subventions. We understand that courts generally uphold legislative interpretations of constitutional amendments so long as they are reasonable and consistent with the purpose of the statute. We think both of those criteria would apply in the case of this change. Counting more subventions at the local level would maintain the spirit of Proposition 4 (1979). The aim of that measure was to keep government appropriations, at all levels of government, below the adjusted 1978‑79 level. This change would still adhere to that basic principal, but would count some spending within local government limits, instead of the state’s limit.

This Change Would Provide a Short‑Term Reduction in Appropriations Subject to the Limit. If the state excluded all funds to local governments, regardless of restriction and/or method of distribution, we estimate there is around $10 billion in existing spending that would no longer count toward the state’s limit, but rather count at the county, city, or special district level. (As of 2018‑19, cities and counties had over $150 billion in collective room under their limits. As a result, changing this definition is unlikely to result in very many local governments exceeding their limits. However, the Legislature could also adopt a mechanism to ensure the change in policy does not cause any single entity to exceed their limits.)

How Can the Legislature Respond in the Long Term?

Under Current Law, State Government Very Likely Cannot Grow More. In the previous section, we outlined three options to address the short‑term budgetary risks currently faced by the state. However, none of these, even all together, would indefinitely forestall the long‑term reality of the state’s constitutional constraints. The reality is that state tax revenues are growing faster than the limit and the size of state government has reached the limit set by voters in the 1970s. Revenue growth has exceeded growth in the limit for a variety of reasons, including faster income growth among higher‑income earners, policy decisions by the Legislature, and growth in school spending. As a result of this differential growth, over the long term the Legislature has only two choices: (1) reduce taxes in order to slow revenue growth or (2) request the voters change the limit. (If the economy does not continue to grow, the Legislature will have other, even more difficult, budget choices to make.)

Reduce Taxes on an Ongoing Basis. The first long‑term alternative for the Legislature is to reduce taxes so that they no longer are growing faster than the limit. Under this alternative, tax revenues and associated spending could still grow, but they could not grow faster than the limit itself. As a result, the Legislature’s ability to make new program expansions would be severely constrained. While the Legislature could still reallocate funds among programs—for example, by spending less in one area, it could make expansions in another—further expansions to programs not coupled with such reductions would not be feasible.

Alternatively, the Legislature Could Request the Voters Change the Limit. The Legislature’s second long‑term option is to ask the voters to approve changes to the SAL. As we noted in a 2021 report on the SAL, there are policy justifications for requesting that the voters change school districts’ limits. For instance, asking for a change to the calculation of districts’ limits—like the changes made to city, county, and special district limits under Proposition 111—would maintain spending limits for schools while providing greater flexibility in the calculation of those limits. However, the voters are permitted to make any changes to the SAL that they deem appropriate. Instead of a narrower change like this, the Legislature also could request more far‑reaching or permanent changes, increases, or modifications to the SAL.

Technical Appendix

In this section, we describe the basic assumptions and specifications of our methodology for arriving at the estimates in this post.

Examined Many Possible Combinations of Key Variables. Several key variables in our analysis—particularly General Fund revenues, special fund revenues, capital gains tax revenues, and personal income growth—cannot be forecasted precisely. Many possible future values of these variables are plausible. Variation in these variables could lead to vastly different budget situations for the state. To account for this variation, we examined 10,000 scenarios comprised of unique combinations of these key variables. Our method seeks to mimic how these variables have varied from year to year historically, as well as how these variables move together over time. Specifically, we modeled these variables (with transformations applied in some cases) using a multivariate normal distribution, with standard deviations and covariances set to match historical levels over the last 40 years. Our analysis does not include variation in some parameters, such as non‑Proposition 98 spending, non‑tax revenue, or state appropriations limit (SAL) exclusions. These parameters reflect the policy choices of the Governor’s budget and therefore leaving them fixed reflects the best estimate of the state’s budget position given those policies. Moreover, variation in any of these parameters would be very narrow compared to variation in tax revenue.

For Each Scenario, Calculated SAL Requirements and SFEU Balance. For each of these 10,000 scenarios, we calculated SAL requirements based on General Fund and special fund tax revenues and holding exclusions fixed. Using those calculated SAL requirements, we estimated Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU) balances for each scenario that:

- Assumed Proposition 98 Spending Would Remain in Test 1. We assumed Proposition 98 spending was a fixed share of General Fund taxes (38.028 percent), with slight variation by year to account for the effects of the state’s Transitional Kindergarten policy. Under our current average daily attendance forecasts, this is a reasonable assumption.

- Assumed SAL Requirements Were Paid in the Second Year of a Two‑Year Net Overage. This analysis assumes SAL requirements are paid in the second year of a net two‑year overage. That is, each time the state has negative room in one year, and a second year of room or negative room that results in net excess revenues across the two‑year period, we assume the state pays for those excess revenues in that second year.

- Assumed Proposition 2 (2014) Infrastructure Spending Offsets Baseline Costs. For each scenario, we calculate a Proposition 2 requirement—including Budget Stabilization Account deposit, debt payments, and infrastructure spending, if applicable—based on General Fund tax revenues, total General Fund revenues, and capital gains revenues. For years in which infrastructure spending was required, we assumed that spending would offset baseline non‑Proposition 98 spending (consistent with the administration’s treatment in their multiyear forecast). This slightly improves the budget bottom line compared to the alternative assumption.

Used Governor’s Budget Non‑Proposition 98 Spending Estimates. We took the Governor’s budget estimates of other spending as given and did not vary these, up or down, with economic and revenue conditions. While this could mean we understated the severity of budget problems during a recession or slightly overstated the severity of budget problems as a result of constitutional spending constraints, these effects generally would be small compared to the figures in this report. For context, in our 2019‑20 Fiscal Outlook analysis, we estimated that non‑Proposition 98 spending would increase about $1 billion at the height of a moderate recession. Meanwhile, the median operating deficits shown in Figure 2 averaged around $10 billion to $12 billion.