January 13, 2023

The 2023‑24 Budget

Overview of the Governor’s Budget

- Introduction

- The Budget Problem

- Budget Condition

- Comments

- Evaluating Recent Augmentations for Reduction or Delay

- Appendices

Executive Summary

Governor’s Emphasis on Spending Solutions to Address Budget Problem Is Prudent. Both our office and the administration project that the state faces a manageable budget problem this year. The Governor addresses the budget problem primarily with spending‑related solutions, as shown in the figure below. Notably, the Governor does not propose using any reserves. This approach is prudent given the downside risk to revenues posed by the current heightened risk of recession. We recommend the Legislature maintain this approach during its own planning process.

Recommend Legislature Plan for Larger Budget Problem. Our estimates suggest that there is a good chance that revenues will be lower than the administration’s projections for the budget window, particularly in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. Given this risk, we recommend the Legislature: (1) plan for a larger budget problem and (2) address that larger problem by reducing more one‑time and temporary spending. Taking these steps would allow the state to mitigate the heightened risk of revenue shortfalls. The Legislature need not adopt the Governor’s spending solutions, however. Recent budgets have allocated or planned tens of billions of dollars for one‑time or temporary spending purposes in 2021‑22, 2022‑23, and 2023‑24. The Legislature can select an entirely different set of spending solutions to address the budget problem. To develop its budget, we recommend the Legislature evaluate recently approved augmentations and only maintain those augmentations that meet certain criteria.

Recommend the Legislature’s Budget Not Include Future Deficits. While the Governor’s budget is balanced under the administration’s estimates for 2023‑24, this is not the case for future years. Specifically, the administration forecasts operating deficits ranging from $4 billion to $9 billion over the multiyear period. We recommend the Legislature avoid enacting a budget that plans for future deficits. To maintain budget balance, the Legislature could convert some spending‑related delays to reductions instead. Alternatively, the Legislature could add new out‑year trigger reductions—in which spending triggers off under certain conditions—or by using other budget solutions, such as revenue increases or cost shifts.

Chapter 1

Introduction

On January 10, 2023, Governor Newsom presented his proposed state budget to the Legislature. In this report, we provide a brief summary of the Governor’s budget based on our initial review as of January 12. In the coming weeks, we will analyze the plan in more detail and release several additional budget analyses.

The Budget Problem

A budget problem—also called a deficit—occurs when resources for the upcoming budget are insufficient to cover the costs of currently authorized services. Because the State Constitution requires the state to pass a balanced budget, the Governor must propose solutions when the administration estimates the state faces a budget problem. The state has many types of solutions—or tools—for addressing a budget problem, but the most important include: reserve withdrawals, spending reductions, revenue increases, and cost shifts (for example, between funds). Due to a deteriorating revenue picture relative to expectations from June 2022, both our office and the administration have anticipated the state faces a budget problem in 2023‑24.

What Is the Budget Problem?

We Estimate the Governor Solved an $18 Billion Budget Problem. We estimate the Governor’s budget addressed an $18 billion budget problem. This is somewhat lower than the $22 billion budget problem the administration has referenced. There are two main sources of this difference. In both cases, the difference stems from what is considered baseline spending—that is, what spending was approved in prior budgets. Specifically, the administration views the following as baseline spending: a $3 billion unallocated set‑aside for inflation‑related costs and a shift of $1.4 billion in authorized capital outlay projects from lease revenue bonds to cash. In contrast, we do not view these items as baseline spending because they were not approved in any budget‑related legislation. Consequently, we do not consider withdrawing the inflation set‑aside or shifting back to lease revenue bonds from cash to be budget solutions. (That is, in our view, these costs would not have occurred absent legislative action and as a result do not contribute to the budget problem the Legislature faces today.)

Comparison to LAO November Outlook. In our Fiscal Outlook released in November 2022, we anticipated the state would face a $24 billion budget problem, somewhat higher than the $18 billion budget problem we estimate the Governor addressed. Relative to our November outlook, the administration’s estimates include:

- $14 Billion in Higher Revenues. The administration’s estimates of revenues (excluding transfers, both between state funds and from the federal government) are $13.6 billion higher across the three‑year budget window compared to our estimates in November. This reduces the size of the budget problem.

- $3 Billion in Higher School and Community College Spending. Reflecting these higher revenue estimates, the administration’s estimates of constitutionally required General Fund spending on K‑14 education is about $2.6 billion higher than our November estimates. This partially offsets the revenue increase described above, increasing the size of the budget problem.

- A $4 Billion Set‑Aside in the SFEU. The Governor proposes the Legislature enact a year‑end balance in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU) of $3.8 billion. The Legislature can choose to set the SFEU balance at any level above zero and so our Fiscal Outlook did not assume a specific balance. (Recent budgets have enacted SFEU balances around $2 billion to $4 billion. The SFEU is used to cover costs of unanticipated expenditures.) Relative to our November estimates, this set‑aside increases the size of the budget problem.

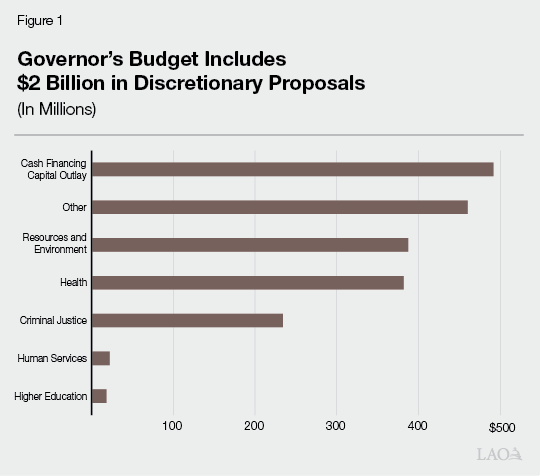

- $2 Billion in Discretionary Spending. The Governor’s budget also includes $2 billion in discretionary spending proposals that are not currently reflected under current law or policy. Figure 1 shows how these proposals are distributed by program area. (Appendix 3, also provides a list of these proposals.) As the figure shows, most of the discretionary increases are to finance some capital outlay projects with cash instead of lease revenue bonds. This increases the size of the budget problem.

- $800 Million in Other Differences. Across the rest of the budget, our estimates of baseline spending—for example, for caseload growth, federal reimbursements, and statutory cost increases—and constitutional requirements—for example, for infrastructure and deposits into reserves—differ, on net, by $800 million. Relative to our estimates, this reduces the size of the budget problem.

How Does the Governor Propose Solving the Budget Problem?

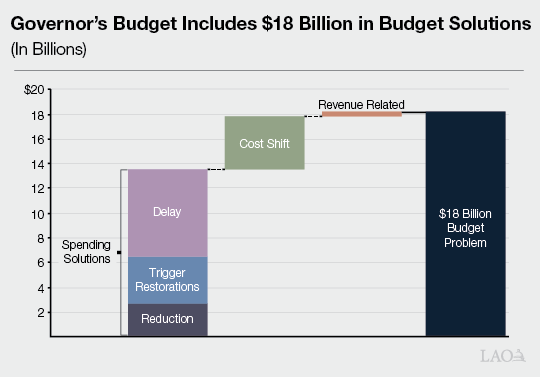

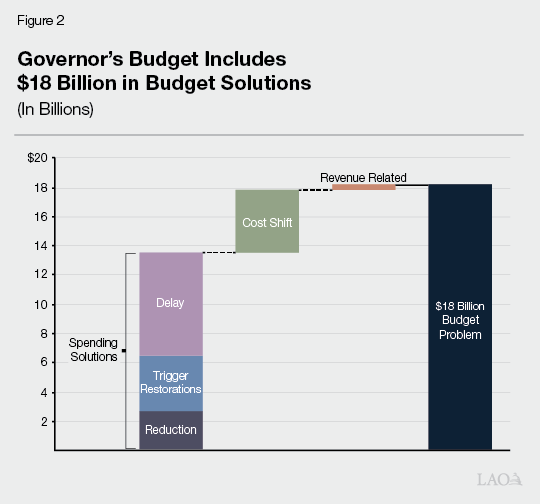

Figure 2 summarizes the budget solutions that this section describes in detail. The Governor’s budget solutions focus on spending. They total $13.6 billion and represent nearly three‑quarters of the total solutions. In addition, the Governor’s budget includes $4.3 billion in cost shifts, which represent nearly one‑quarter of the total. Notably, the Governor’s budget does not propose using any reserves to address the budget problem.

Spending‑Related Solutions

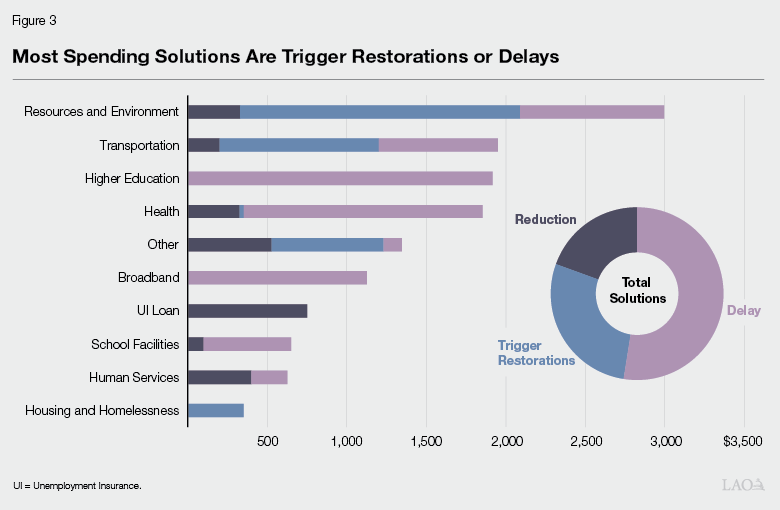

The Governor’s $13.6 billion in spending‑related budget solutions can be categorized into three types: reductions, delays, and trigger restoration. Nearly all of these solutions would apply to one‑time and temporary spending. Figure 3 shows how the spending solutions are broken out across program area and type. Appendix 1 provides a list of these proposed solutions. The remainder of this section describes each of these types in turn.

$7.1 Billion in Delayed Spending. We define a delay as an expenditure reduction that occurs in the budget window (2021‑22 through 2023‑24), but has an associated expenditure increase in a future year of the multiyear window (2024‑25 through 2026‑27). That is, the spending is moved to a future year. About half of the Governor’s spending‑related solutions are delays. Most of the spending delays are in higher education, health, and broadband. They result in net cost increases by 2024‑25, with the largest cost increases occurring in 2025‑26.

$3.8 Billion in Spending Reductions Subject to Trigger Restoration. The Governor’s budget proposes making nearly one‑third of all spending‑related solutions subject to trigger restoration language. Under this proposed language, program spending that otherwise would have occurred in 2023‑24 would not be allocated as part of the June budget act. However, if in January 2024 the administration estimates there are sufficient resources available to fund these expenditures, those programs would be restored halfway through the fiscal year. Many of the spending solutions in natural resources and environment, transportation, and housing and homelessness are subject to this trigger restoration language.

$2.6 Billion in Spending Reductions. We define a spending reduction as the elimination of an augmentation previously approved under current law or policy. The Governor’s budget includes nearly $3 billion in reductions, the largest of which is withdrawing a discretionary principal payment on state’s unemployment insurance loan (which otherwise is paid by employers’ payroll taxes). Less than 20 percent of the total spending solutions are reductions.

Cost Shifts

In addition to spending solutions, we estimate the Governor’s budget includes $4.3 billion in cost shifts. Cost shifts occur when the state moves costs between entities or fund sources. For example, shifting spending from the General Fund to special funds or, as has been done in prior budgets, shifting costs from the state to local governments. Major cost shift proposals in the Governor’s budget include: (1) shifting $1.5 billion in costs for zero‑emission vehicles from the General Fund to the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, (2) making $850 million in loans from special funds to the General Fund, (3) temporarily transferring $300 million from the health care affordability reserve fund to the General Fund, and (4) shifting $500 million in transportation‑related costs from the General Fund to transportation‑related special funds. Appendix 2 provides a full list of these proposed cost shifts.

Revenue Related

We estimate the Governor’s budget includes about $350 million in revenue‑related solutions. The key item in this category is a proposal for the state to reauthorize a tax on managed care organizations that draws down additional federal funds and offsets costs in Medi‑Cal. While the fiscal impact of this reauthorization would be small in the budget window—an estimated $300 million in 2023‑24—the effect would be much larger in future years, rising to roughly $2 billion in General Fund savings as early as 2024‑25. (Reauthorizing this tax would require federal approval.) (Appendix 2 also includes a list of proposed revenue‑related solutions.)

Budget Condition

In this section, we describe the overall condition of the General Fund budget after accounting for the Governor’s budget proposals and solutions. We also describe the condition of the school and community college budget.

General Fund Budget

Figure 4 shows the General Fund condition based on the Governor’s proposals and using the administration’s estimates and assumptions. Under these estimates and assumptions, the state would end 2023‑24 with $3.8 billion in the SFEU.

Figure 4

General Fund Condition Summary

(In Millions)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$41,102 |

$52,713 |

$21,521 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

233,891 |

208,883 |

210,174 |

|

Expenditures |

222,280 |

240,076 |

223,614 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$52,713 |

$21,521 |

$8,081 |

|

Encumbrances |

4,276 |

4,276 |

4,276 |

|

SFEU balance |

48,437 |

17,245 |

3,805 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA |

$19,867 |

$21,487 |

$22,398 |

|

SFEU |

48,437 |

17,245 |

3,805 |

|

Safety net |

900 |

900 |

900 |

|

Total Reserves |

$69,204 |

$39,632 |

$27,103 |

|

BSA = Budget Stabilization Account and SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties. |

|||

Under Governor’s Budget, Reserves Would Total $27 Billion by End of 2023‑24. Under the Governor’s budget, general purpose reserves would total $27 billion by the end of 2023‑24. In addition, the state would have $8.5 billion in the School Reserve, available only for school and community college programs. Under the Governor’s proposals, the state would continue to make its otherwise constitutionally required deposits, including a deposit of $911 million into the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) and $365 million into the School Reserve in 2023‑24. The deposits could be suspended if the Governor declared a budget emergency, as we describe in the nearby box.

Budget Emergency Calculation Under Governor’s Budget

Legislature Can Make a BSA Withdrawal Under Two Conditions. The Legislature can only suspend mandatory deposits or make withdrawals from either of its two constitutional reserves—the Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) and the School Reserve—if the Governor declares a budget emergency. The Governor may declare a budget emergency in two cases: (1) if estimated resources in the current or upcoming fiscal year are insufficient to keep spending at the level of the highest of the prior three budgets, adjusted for inflation and population (a “fiscal budget emergency”), or (2) in response to a natural or man‑made disaster.

Legislature Cannot Access Most of Its Constitutional Reserves Without a Fiscal Emergency Declaration by the Governor. Under our interpretation of the constitutional rules and our estimates using the administration’s revenue and economic projections, a fiscal emergency would be available in 2023‑24, but not for 2022‑23. (In the case of a fiscal emergency, the Legislature only can withdraw the lesser of: [1] the amount of the budget emergency, or [2] 50 percent of the BSA balance.) However, because the Governor did not declare a fiscal emergency, the Legislature cannot make these withdrawals to address the budget problem. That said, there is a small “optional” balance in the BSA (which was not deposited pursuant to the constitutional rules), which mostly likely could be accessed by the Legislature without a fiscal emergency declaration by the Governor. This optional balance totals $1.8 billion.

Administration Plans for Multiyear Operating Deficits. The Governor’s budget also includes estimates of multiyear revenues and spending. Under those projections, and the Governor’s budget proposals, the state faces operating deficits of $9 billion in 2024‑25, $9 billion in 2025‑26, and $4 billion in 2026‑27. These figures represent future budget problems. That is, if the Governor’s budget projections are accurate, the state would have to address deficits of these amounts in each of these future years.

State Appropriations Limit (SAL) Estimates Still Unknown. In recent years, the SAL has placed constraints on the Legislature’s budget choices. (For more information about the SAL, see our report, The 2022‑23 Budget: Initial Comments on the State Appropriations Limit Proposal.) Under our November estimates of revenues and spending, the state would have a good amount of room under the limit in the budget window. However, the administration’s revenue and spending estimates are different than ours, which is likely to yield differences in the SAL calculation. As of this writing, we have not yet received information from the administration on these estimates.

School and Community College Budget

Proposition 98 Minimum Guarantee Down Over Budget Window. The State Constitution sets a minimum annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges. The minimum guarantee is met with a combination of General Fund and local property tax revenue. Compared with the estimates included in the June 2022 budget plan, the administration revises its estimates of the minimum guarantee up $178 million in 2021‑22 and down $3.4 billion in 2022‑23. The increase in 2021‑22 is primarily attributable to higher local property tax revenue, while the decrease in 2022‑23 primarily reflects lower General Fund revenue estimates. For 2023‑24, the administration estimates the minimum guarantee is $108.8 billion—$1.5 billion below the 2022‑23 level enacted last June.

Budget Includes Additional School and Community College Proposition 98 Spending. Although the minimum guarantee decreases over the budget period, funding is available for spending increases due to the expiration of one‑time initiatives and lower‑than‑anticipated program costs. The Governor’s budget includes a net of $6 billion in new Proposition 98 spending—a total of $7.4 billion in spending increases, offset by $1.4 billion in spending reductions. Most of the spending increases are to (1) cover the cost of providing an 8.13 percent statutory cost‑of‑living adjustment (COLA) for school and community college programs ($5.5 billion) and (2) continue planned program expansions ($920 million). The cost of this new spending is offset by the Governor’s proposals to reduce previously approved one‑time funding for (1) the Arts, Music, and Instructional Materials Discretionary Block Grant by $1.2 billion and (2) community college facilities maintenance and instructional equipment by $213 million.

Comments

Budget Year

Governor’s Emphasis on Spending Solutions, Instead of Reserves, Is Prudent. The Governor’s budget addresses the estimated budget problem without using funds from the state’s reserves. Moreover, the Governor does not suspend the 2023‑24 deposit into the BSA, which could otherwise occur if a fiscal emergency were declared (see box above). The administration noted that, if revenues decline further, using reserves would be considered, but for now relies only on other types of budget solutions—particularly spending‑related reductions and delays. This approach is warranted given: (1) the manageable size of the budget problem and (2) the downside risk to revenues posed by the presently heightened risk of recession. (For a more on this issue, see our report: The 2023‑24 Budget: California’s Fiscal Outlook.) We recommend the Legislature maintain this approach during its own planning process.

Recommend the Legislature Plan for a Larger Budget Problem by Identifying More Spending Reductions. Our estimates suggest that there is a good chance that revenues will be lower than the administration’s projections for the budget window, particularly 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. Nonetheless, the Governor’s budget trigger restoration proposals implicitly place more emphasis on revenue upside—suggesting the administration anticipates that revenues are more likely to be higher, not lower, than their current projections. Given the greater downside risk, however, we recommend the Legislature: (1) plan for a larger budget problem and (2) address that larger problem by reducing more one‑time and temporary spending. If the Legislature wanted to, it could make these spending reductions subject to trigger restorations. Taking these steps would allow the state to mitigate the heightened risk of revenue shortfalls. Moreover, developing a larger set of potential budget solutions now allows the Legislature to do so deliberately rather than under the pressure of the May Revision.

Proposal Generally Maintains Spending on Health and Human Services, but Reduces Other Legislative Priorities. In general, the Governor’s budget does not make large reductions to health and human services programs. Rather, the Governor’s spending‑related reductions, including reductions with trigger restorations, are concentrated in natural resources, environmental protection, and transportation, areas which also received large one‑time and temporary augmentations in recent budgets. (For more information on recent augmentations, please see: How Program Spending Grew in Recent Years.) Spending solutions in these areas might be warranted because these programs: (1) have other funding to at least partially accomplish some of the intended outcomes and (2) still would receive sizeable augmentations. However, some of the specific reductions the Governor is proposing are in areas where the Legislature has signaled clear priorities.

Due to Budget Problem, New Proposals Require Reductions to Planned Spending. In addition to addressing a budget problem, the Governor’s budget proposes $2 billion in new discretionary spending mainly in capital outlay financing, resources and environment, and other miscellaneous program areas. Because of revenue shortfalls, these new spending amounts contribute to a larger budget problem and necessitate additional budget solutions. That is, for each dollar of new proposals, another dollar of solutions would be required. While the Legislature might share some of these priorities, it need not adopt all, or even any, of the associated proposals. Rejecting them would reduce the budget problem and the number of solutions necessary.

Recommend Legislature Evaluate Recent Augmentations and Consider Other Budget Solutions. Recent budgets have allocated or planned tens of billions of dollars for one‑time and temporary spending purposes in 2021‑22, 2022‑23, and 2023‑24. The Governor’s budget identifies one set of recent augmentations to reduce or delay in order to address the budget problem. The Legislature can select entirely different spending solutions. To assist the Legislature in this effort, we have provided a list of large augmentations provided in recent budgets in Appendix 4 and a set of criteria for evaluating them for reduction or delay in “Chapter 2” of this report. The Legislature could apply these criteria through its budget oversight hearings throughout the next few months.

Proposal Maintains Statutory COLA Adjustments, but Does Not Include Other Inflation‑Related Augmentations. Due to differences in law and policy across the budget, the state accounts for inflation differently in the school and community college budget versus the other programs. In particular, school and community college programs receive an annual COLA under statute—8.13 percent this year. Across the rest of the budget, statutory and other automatic inflation adjustments for programmatic spending are more limited. While the Governor’s budget funds those inflation adjustments that exist under current law, in many program areas, there are no such automatic adjustments. As the Legislature works to address the budget problem, we suggest policymakers consider the unique impacts of inflation on each of the state’s major spending programs in conjunction with possible budget solutions. (See our report, The 2023‑24 Budget: Considering Inflation’s Effect on State Programs, for more information.)

Multiyear

Although Timing Differs, LAO and Department of Finance Revenue Estimates Very Close… The Governor’s budget downgrade to the revenue outlook over the next several years is very similar to the one in our Fiscal Outlook. Although the timing of revenue shortfalls is somewhat different, the overall revenue decline through 2026‑27 is very similar. Across all six years of the budget window and multiyear period, the administration’s estimates of revenues from the state’s three largest taxes are $108 billion lower than the budget act, very similar to our Fiscal Outlook estimate of $101 billion.

…But Governor’s Spending Plan Relies on More Resources Being Available. The Governor’s budget includes operating deficits ranging from $4 billion to $9 billion over the multiyear period. This means that, if the administration’s revenue estimates are accurate, further budget solutions in these amounts will be required in those years. If revenues are lower than the administration currently projects, even more reductions would be needed.

Recommend the Legislature’s Budget Not Include Future Deficits. In contrast to the Governor’s approach, we recommend the Legislature avoid enacting a budget that plans for future deficits. A key way to accomplish this would be by reducing proposed spending delays and making more spending‑related reductions instead. However, the Legislature also could address future year deficits by adding trigger reductions (rather than restorations)—to trigger off more multiyear spending if needed—or by using other budget solutions, such as revenue increases or cost shifts.

Chapter 2

Evaluating Recent Augmentations for

Reduction or Delay

The Governor’s budget proposes one possible list of spending‑related solutions, but there are many other choices the Legislature could make. In developing an alternative approach, we recommend the Legislature treat all recent one‑time or temporary General Fund augmentations (outside of the school and community college budget) like new proposals and reevaluate them in light of the budget problem. To determine which augmentations to maintain, we recommend the Legislature use the criteria laid out below. Specifically, the Legislature could direct the administration to justify these proposals according to these criteria in its presentations to the budget committees. Under this approach, only those proposals that meet most of the criteria would be appropriated as part of this year’s budget package.

In Appendix 4 we list all of the large one‑time and temporary augmentations provided by prior budgets in 2021‑22, 2022‑23, and 2023‑24. The Legislature can use this list as a starting place for creating its own proposed solutions.

Start With 2023‑24 Augmentations… We recommend the Legislature first review augmentations planned for 2023‑24 as these funds have not been disbursed to departments or other entities, like local governments. Consequently, reducing or pausing the funding would not impact ongoing services. Moreover, while some of these augmentations continue temporary programs from recent years, many of them start entirely new programs and initiatives. Delaying or reducing funding for these initiatives would cause limited disruption.

After reviewing 2023‑24 augmentations, we recommend the Legislature also reevaluate certain 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 augmentations. In some cases, funding may not yet be disbursed or the total amount required may be less than anticipated. (In many cases, however, the funds may not be available for reversion.)

…Identify More Solutions Than the Governor’s Budget. We recommend the Legislature identify more than $14 billion in spending reductions and delays. To hedge against possible lower revenues in May, we also recommend the Legislature plan for a larger budget problem by identifying more than $6 billion in spending reductions. Identifying these solutions now gives the Legislature more time to weigh these difficult choices carefully.

Criteria

This section lays out the criteria we recommend the Legislature use to evaluate whether recent augmentations should be maintained in light of the budget problem. (These criteria are intended to apply to General Fund discretionary augmentations outside of the school and community college budget.)

- The Augmentation Has a Clear Goal That Aligns With Legislative Priorities. Assess whether the augmentation targets a well‑defined policy problem that is a priority of the Legislature to address.

- The Projects or Activities Are Specific and Address the Legislature’s Goal. Assess whether prior budget plans aligned the specific projects and activities with the Legislature’s policy goals. If not, the Legislature could consider whether to delay or reduce this spending until more planning can be done.

- The Underlying Needs Have Not Changed. In some cases, since the augmentation was approved, the state might have new information or events might have developed such that the underlying need for the program or policy has changed and funding could be reduced.

- Early Indications Show That the Projects or Activities Are Meeting Their Goals. In cases where one‑time or temporary spending in 2023‑24 continues prior similar efforts, evaluate whether the funding has been effective and whether the administration has been implementing the program with fidelity toward the Legislature’s vision.

- The Involved Entities Have the Capacity to Administer the Initiative. There are a few reasons that capacity concerns might arise, creating opportunities for reevaluating spending. Some departments or other entities received multiple rounds of funding for the same purpose over several years. In cases where an entity has encountered issues distributing early rounds of funding, the later rounds likely could be paused without much near‑term impact on the program. In other cases, departments and other entities have received multiple rounds of funding for different programs and projects, straining capacity across program areas. These also could provide cases where the Legislature might wish to pull back program funding, allowing the entity to focus on the highest‑priority areas.

- Pausing or Delaying the Appropriation Would Have Significant Negative Distributional Impacts on Populations of Concern. In some cases, pausing or delaying an augmentation could raise equity concerns, for instance if doing so would disproportionately reduce services or assistance to populations of concern. In these cases, pausing or delaying the augmentation could exacerbate an underlying disparity.

- The Augmentation Does Not Duplicate Federal or Special Fund Activities. In some cases, legislative action might have supplemented, or even duplicated, federal funding provided at other points in time. These too might provide cases for reevaluation. (That said, if the state dollars are pulling down additional federal resources, greater scrutiny should be applied in considering a pause.) In other cases, the Legislature might have the flexibility and funding capacity to redirect special fund revenues to a General Fund purpose.

- The Projects or Activities Primarily Meet an Acute Need. To the extent a program only has longer‑term benefits, there might be an argument for pausing or delaying it while the opportunity costs of those funds are higher—and could be directed toward serving the state’s more acute needs.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Spending Solutions

Appendix 2: All Other Solutions