LAO Contact

September 7, 2023

MOU Fiscal Analysis: Bargaining Unit 6 (Corrections)

On Saturday, August 26, 2023, the administration released a proposed labor agreement between the state and Bargaining Unit 6 (Corrections). Unit 6 consists of correctional officers, parole agents, and other correctional staff who provide custody, supervision, and treatment of people in state custody. As of July 3, 2023, Unit 6 members work under the terms and conditions of an expired memorandum of understanding (MOU). Compensation costs for Unit 6 members and their managers constitute about one-third of the state’s General Fund state employee compensation costs. Unit 6’s current members are represented by the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA). This analysis of the proposed agreement fulfills our statutory requirement under Section 19829.5 of the Government Code. The administration has posted on the California Department of Human Resources’ (CalHR’s) website the agreement, a summary of the agreement, and a summary of the administration’s estimates of the proposed agreement’s fiscal effects.

Background

Unit 6 in Context of State Workforce

Represents 10 Percent of State Workforce. The monthly average size of the state workforce in 2022 was 252,300 full-time equivalent employees. About 10 percent of these employees were a member of Unit 6.

Accounts for About One-Third of State General Fund Payroll Costs. The annualized April 2023 state salary and salary-driven benefit costs paid from the General Fund was $17.8 billion. The salary and salary-driven costs for rank-and-file and affiliated excluded employees for Unit 6 constituted roughly one-third of these General Fund payroll costs.

Prison Costs

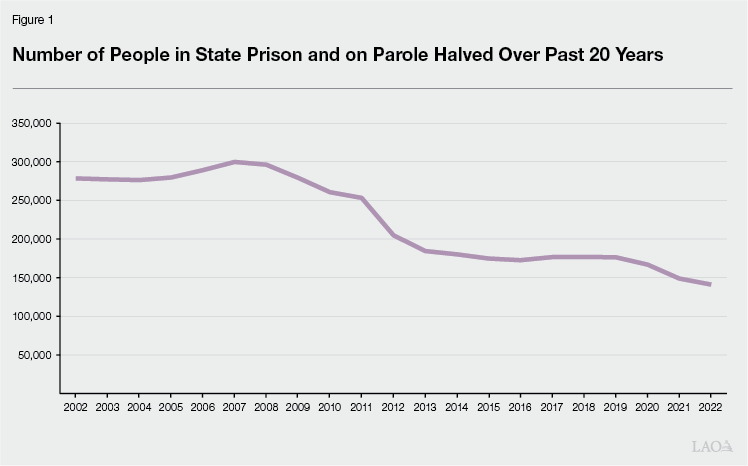

Number of People in Prison and on Parole Has Decreased but Costs Have Not. As Figure 1 shows, the number of people in state prison or on parole has decreased significantly over the past 20 years such that the number of people in state prison or on parole in 2022 is about one-half the number in 2002. The state correctional population is projected to continue to decline somewhat through June 2027. The decline in prison population has allowed the state to reduce prison capacity without violating a federal court-ordered limit on prison overcrowding. Specifically, in 2021, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) completed a multiyear drawdown of people housed in contractor-operated prisons. In addition, the department deactivated various state-operated prison facilities since 2021. Specifically, CDCR deactivated Deuel Vocational Institution in Tracy in 2021, California Correctional Center in Susanville in 2023, and eight yards at various prisons between 2021 and 2023. However, despite these declines in the number of people in prison and the number of facilities used to house them, CDCR spending generally has increased. Specifically, CDCR operational spending increased from $11.8 billion in 2017‑18 to an estimated $14.8 billion in 2022‑23—a 25 percent increase. With inflation during this period rising 23 percent, this means that growth in CDCR operational spending slightly outpaced inflation. The budget assumes that CDCR operational spending will decrease by $415.8 million in 2023‑24 relative to 2022‑23 levels; however, this does not reflect any increased costs resulting from new labor agreements. Employee compensation costs are a major driver in CDCR operating costs. If the proposed Unit 6 and other agreements are ratified by the Legislature, costs will be higher than they were in 2022‑23.

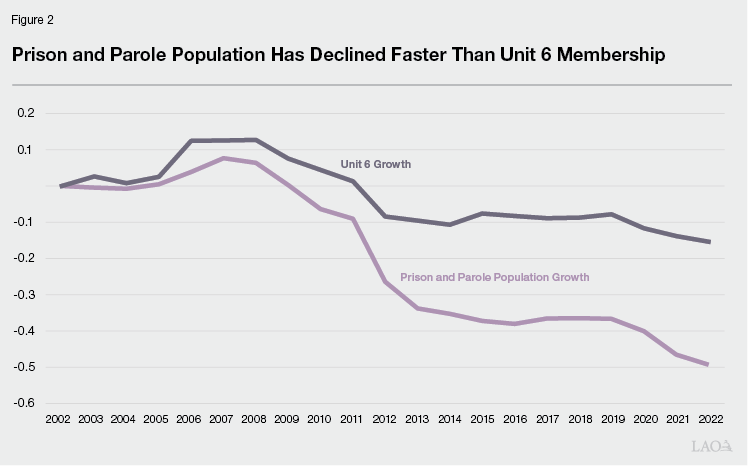

Number of People in Prison and on Parole Has Declined Faster Than Number of Unit 6 Members. Over the past 20 years, the number of Unit 6 members has decreased as the state has employed fewer correctional staff. However, the decline in the number of Unit 6 members has been less than the decline in prison and parole populations. As Figure 2 shows, while the prison and parole populations decreased by 50 percent during the period, the number of Unit 6 members decreased only 15 percent. This trend is, in large part, related to a federal court order that required California to reduce prison overcrowding. Specifically, despite the decline in the number of people in prison, the state had to maintain existing prison capacity, as well as build and staff new prison capacity, in order to comply with the limit.

Compensation Studies

Important Tool for Any Employer. A compensation study aggregates and analyzes internal and external data so that an employer can compare the compensation structure it offers to what is provided by similar employers with similar employees in the same labor market. Employers in both the public and private sectors commonly conduct regular compensation studies to monitor changes in the labor market. A well designed and executed compensation study is a valuable tool that provides a number of benefits, including helping employers (1) determine if they are compensating employees fairly and at a level that will attract skilled workers, (2) allocate limited resources efficiently and effectively by not paying employees more than is required to retain them, (3) identify internal equity issues regarding their compensations structure, and (4) establish a structure for their decision-making process when making changes to their compensations structure. In addition, for public employers, a compensation study brings transparency to the decision-making process such that employees, policymakers, and the public all have the same information against which to evaluate proposed changes in compensation.

Comparators and Methodology Key to Understanding Purpose and Usefulness of Compensation Study. Not all compensation studies are equally relevant or helpful in assessing the issues we identified above. Factors that affect the quality of a compensation study include (1) the similarity of jobs that are included in the study for comparison, (2) the extent to which the elements of compensation compared capture the total compensation earned by employees, and (3) the similarity and relevance of employers selected for comparison.

State Law Requires General Salary Increases (GSIs) Be Justified… A GSI adjusts the entire salary range for a classification such that all employees within that classification receive the pay increase. Section 19826 of the Government Code specifies that CalHR shall establish salary ranges for state classifications “based on the principle that like salaries shall be paid for comparable duties and responsibilities.” Further, the law requires that—when establishing or changing pay ranges—“consideration shall be given to the prevailing rates for comparable service in other public employment and in private business.” These requirements necessitate that changes to state salaries be justified based on comparisons to other comparable employers.

…And Requires CalHR to Conduct Salary Studies. Since 1981, Section 19826 has required the administration to submit to the Legislature and bargaining units a report containing the department’s findings related to salaries of employees in comparable occupations in private industry and other governmental agencies. Originally, the law required that this report be submitted to the Legislature on or before January 10 of each year. Chapter 465 of 2003 (SB 624, Committee on Public Employment and Retirement) changed the frequency of this report such that the report was required to be submitted to the union and the Legislature at least six months before the end of the term of an existing MOU. Chapter 39 of 2023 (AB 130, Committee on Budget) amended the section such that the law now requires that CalHR submit to the unions and Legislature a report containing the department’s findings relating to the salaries of employees in comparable occupations in private industry and other governmental agencies (1) on February 1, 2025 and biennially thereafter for 11 bargaining units and (2) on February 1, 2026 and biennially thereafter for the remaining ten bargaining units (including Unit 6). If this requirement under law conflicts with provisions of a ratified MOU, the law specifies that the ratified MOU shall be controlling.

Annual Budget Act Imposes Additional Requirements of Total Compensation Studies. As the administration indicated in its 2013 total compensation study for Unit 6, provisional language under CalHR’s budget item (Item 7501‑001‑0001) of the annual budget act “requires that in addition to salaries the report must include total compensation and geographic comparisons.” In the department’s total compensation reports for most bargaining units, these requirements are fulfilled by (1) comparing both salary and ancillary benefits offered by the state and comparator employers and (2) evaluating how the state’s total compensation compares with other employers statewide as well as in four regions across the state (specifically, the regions surrounding the San Francisco Bay, Sacramento, Los Angeles, and San Diego).

Evaluating State Correctional Officer Compensation

State Law Requires Administration to Take Into Consideration Compensation Offered by Other Large Employers of Peace Officers in California. Section 19827.1 consists of two paragraphs. The first paragraph expresses legislative intent. Specifically, the first paragraph asserts that, at the time the law was passed in 1986, (1) there existed a “historic problem of recruitment and retention of peace officers in the Department of Corrections and the Department of Youth Authority” and that (2) “salaries must be improved and maintained by the state” to address the “continuing need to recruit new officers to fill vacancies, retain seasoned correctional peace officers to reduce turnover rates, and provide comparability in pay to effectively compete with large peace officer employers and ensure necessary staffing levels.” The second paragraph directs CalHR to “take into consideration the salary and benefits of other large employers of peace officers in California.”

Last Unit 6 Total Compensation Study Found State Correctional Officers Compensated High Above Market. The last Unit 6 compensation study that CalHR submitted to the Legislature in compliance with the requirements under Section 19826 used data from 2013. That compensation study found that state correctional officers were compensation 40.2 percent above their local government counterparts and 28.1 percent above their federal government counterparts.

Expired MOU Requires CalHR to Discuss Section 19826 Compensation Study Methodology With Union. First appearing in the 2016 Unit 6 MOU, the expired Unit 6 MOU includes language related to the compensation study required by Section 19826. The expired MOU’s provision is Article 15.19 and requires that:

Within ninety (90) days of ratification of this MOU, the parties agree to form a Joint Labor Management group who will meet to discuss the criteria, comparators and methodology to be utilized for [Bargaining Unit] 6 in the next Total Compensation Report created pursuant to Government Code section 19826. The Joint Labor Management group will be comprised of no more than two (2) representatives from each of the following: CCPOA, CalHR, CDCR and Department of Finance. The first meeting of the Joint Labor Management group will occur no later than eighteen (18) months prior to the expiration of the MOU.

It is important to note that the text of Article 15.19 (1) does not relieve CalHR of the requirements established by Section 19826 and the annual budget act related to the total compensation study produced by CalHR—including that the report be submitted to both the Legislature and the union, (2) does not make any reference to Section 19827.1, and (3) specifies that any discussion between the administration and the union related to the compensation study will occur before CalHR begins its compensation study.

No Compensation Study Provided to the Legislature in 2018. Despite the statutory requirements to submit a compensation study to the Legislature prior to the expiration of the 2016 MOU, none was provided. The administration states that it met with Unit 6 as provided under Article 15.19 described above and that CalHR completed a compensation study based on the methodology agreed to by CCPOA and the administration. Although the administration provided the compensation study to CCPOA in 2018, the Legislature did not receive it. CalHR stated that it had agreed not to submit to the Legislature the compensation study until all of CCPOA’s questions and concerns had been addressed.

Since 2019, our office has asked on numerous occasions for the administration to provide us a copy of the 2018 compensation study or to provide us information about the methodology used in that study. To date, the administration has refused to provide the study itself or to share any information about the study’s methodology or findings. The administration asserts that the 2018 compensation study and all information related to it is confidential pursuant to Section 7928.405 of the Government Code—a section from the California Public Records Act (CPRA). The administration states that this law classifies as confidential any work, including draft reports, from a Joint Labor Management Committee (JLMC). The administration views the 2018 compensation study as a draft product of a JLMC process. Accordingly, the administration’s position means the Legislature is not privy to the draft report or any information or documentation related to it.

2022 Unit 6 CalHR Compensation Study

Study Submitted After Statutory Deadline. The term of the expired MOU ended on July 2, 2023. As discussed above, Section 19826 of the Government Code before Chapter 39 amended it in July 2023, required CalHR to submit its total compensation study for a bargaining unit six months before the expiration of the bargaining unit’s MOU. To comply with state law at the time, CalHR should have submitted a Unit 6 compensation study to CCPOA and the Legislature by January 2023. While we do not know when CalHR submitted the study to CCPOA, the department did not meet its statutory deadline. The study was submitted to the Legislature in April 2023. This study was revised in August 2023.

Methodology and Report Product of JLMC Process. Pursuant to Article 15.19 of the expired MOU, the parties discussed the methodology to be used to develop a new Unit 6 compensation study. Because the administration has not provided any information about the 2018 compensation study, we do not know how the methodology or findings of the 2022 compensation study differs from the methodology or findings of the 2018 methodology. We also do not know how the issues that prevented the 2018 compensation study from being submitted to the Legislature were resolved to result in the release of the 2022 study.

Study Design and Findings

Stated Intent of Report. The report specifies that the findings of the report do not define the appropriate level of compensation for state correctional officers. Instead, the stated purpose is to compare the state’s total compensation costs with other local government employers in California.

Employers Surveyed. The report compares employer costs to pay for elements of compensation provided to state correctional officers with the costs incurred by six county employers to compensate similar employees. The six counties included in the study are the six counties that employ the largest number of peace officers. Specifically, the study compares the state’s compensation costs with the costs incurred by the Counties of Los Angeles, Orange, Santa Clara, Sacramento, San Bernardino, and San Diego.

Classifications Compared. The survey asked each county employer to report compensation costs related to specific classifications. Figure 3 shows the classifications that were used for comparison.

Figure 3

Employers and Classifications

Compared in 2023 Unit 6 Compensation Study

|

Employer |

Classification Title |

|

State of California |

Correctional Officer |

|

Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department |

Deputy Sheriff |

|

Orange County Sheriff's Department |

Deputy Sheriff I |

|

Santa Clara County Sheriff's Department |

Sheriff Correctional Deputy |

|

Sacramento County Sheriff's Department |

Deputy Sheriff |

|

San Bernardino County Sheriff's Department |

Deputy Sheriff |

|

San Diego County Sheriff's Department |

Deputy Sheriff, Detentions/Court Services |

Elements of Compensation Included. CalHR surveyed the six counties to provide employer compensation cost data as of January 31, 2022 for the classifications indicated above. The report seeks to compare separately the compensation cost of entry-level correctional officers with entry-level deputy sheriffs (after graduating from the academy) and full journey-level correctional officers with full journey-level deputy sheriffs. This distinction is important because employees who have worked for the state or for one of the counties for a significant number of years have higher compensation than new officers who recently graduated from the academy. Newly hired employees typically (1) are in a lower step of the classification pay range (earning lower base salaries), which results in lower employer costs to salaries and any salary-driven benefits; (2) are not eligible for payments that are based on length of service until they have worked for at least a specified time; (3) typically are not eligible for payments based on special certifications or training as they have less experience than more senior employees; and (4) were first hired after 2013, meaning that they likely receive a lower pension benefit pursuant to state law. Below are the elements of compensation included in the study.

Pay. The report includes base wages and specified other payments to employees included as compensation. For base pay, the report assumes that entry-level employees are paid at the bottom step of their classification’s salary range and journey-level employees are assumed to be paid at the top step of their classification’s salary range. For the other payments included in the study—education pay, payments provided for certifications attained by employees from the California Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training, and payments received by employees who have worked for the employer for more years—the study assumes that entry-level employees receive the lowest available payment and journey-level employees receive the highest available payment.

Health, Dental, and Vision Benefits. The report assumes that both entry-level and journey-level employees are enrolled in employer-sponsored health, dental, and vision insurance with policy coverage for a family.

Retirement Benefits. As we discuss in greater detail later, the study includes employers’ costs towards pension benefits and retiree health benefits.

Methodology. CalHR developed and distributed a survey to the six county employers to collect the employer costs to provide the specified elements of compensation. CalHR then took a simple average of the employer costs across the six employers to compare total compensation costs of the six employers with that of the state.

Findings. Based on the comparators and methodology used in the study, CalHR found that state correctional officer compensation lags the compensation provided to similar employees by the six counties. This means that CalHR found that state correctional officers are compensated less than similar employees in the six counties. Specifically, the study (as revised) found that (1) the state’s salaries (not including benefits) lag 28 percent for entry-level employees and 10 percent for full journey-level employees and (2) the states’ total compensation (salary plus benefits) lags 33 percent for entry-level employees and 23 percent for full journey-level employees.

Retirement Security

Factors That Affect Retirement Security. The amount of money that a person can expect to need in retirement depends on a variety of factors that are unique to the individual’s circumstance. Some of the key factors to consider when assessing retirement security include: the individual’s expected lifespan, the age at which an individual retires. the standard of living the individual expects to live in retirement, the individual’s savings level upon retirement, and any employer-sponsored pension or other income benefit. A person’s level of retirement security depends in part on how much of their pre-retirement income can be replaced after retiring through a combination of what often is referred to as the “three-legged stool” of retirement in the United States: (1) Social Security benefits, (2) employer-sponsored retirement plans, and (3) personal financial assets. There is no one-size fits all replacement ratio; however, a number of researchers have identified that the replacement ratio for the median individual is between 66 percent and 75 percent of preretirement income. In general, lower-income workers would need a higher replacement ratio because they would be expected to spend a higher proportion of their income on food, clothing, housing, transportation, health care, and other essentials.

Employer-Sponsored Retirement Plans. There are two broad categories of employer-sponsored retirement plans: defined benefit plans and defined contribution plans. In both types of plans, employers and employees might make contributions towards the plan over the course of employees’ careers. The primary difference between the two plans is (1) who makes investment decisions and (2) who bears the risk of investment losses. In the case of a defined benefit plan, the employer chooses how the funds are invested and bears all the risk of investment loss—the employee is provided a guaranteed annuity in retirement. In the case of a defined contribution plan, the employee chooses how contributions are invested and bears all the risk of investment losses. Unlike a defined benefit plan, there is no guarantee—either by the employer or by government—of assets held in a defined contribution plan.

Hybrid Employer-Sponsored Retirement Plans. Some employers offer employees a hybrid plan that combines elements of traditional defined contribution and defined benefit plans. For example, a parallel hybrid plan provides employees both an employer-funded defined benefit pension and an employer-funded defined contribution plan. Typically, the defined benefit and defined contribution components of these types of plans are smaller than if the employer offered only a defined benefit or only a defined contribution plan. The amount of money that the employer contributes to each plan typically is based on an employee’s total pay.

Correctional Officer Retirement Income Benefits

Not Eligible for Social Security. When Social Security was initially established in 1935, all federal, state, and local government employees were excluded from the program. Beginning in the 1950s, the program was changed to allow governments to enroll some of their employees in the federal program. By 1991, the program covered all federal employees and most state and local government employees. Under federal law, state and local government employers may continue to exclude some employees from Social Security coverage, but only if those employees are enrolled in a retirement plan that meets federal regulations requiring at least a specified level of benefits. In California, peace officers and teachers generally are excluded from Social Security.

Defined Benefit Pensions a Long-Standing and Significant Element of Compensation in California State Employment. The state has included in its compensation package a defined benefit pension since 1932. The benefit, as it exists today, provides retired state employees a guaranteed annuity that is determined by (1) the employee’s date of hire, (2) the number of years of service the employee has upon retirement, and (3) the employee’s age at retirement. These benefits are paid for through contributions towards two components of the benefit’s cost, discussed below.

Normal Cost. The normal cost is the amount of money that actuaries determine must be set aside for the benefit employees earn today so that the contribution and any future investment returns on that contribution are sufficient to pay for the benefit after the employee retires. Under the Public Employees’ Pension Reform Act of 2013 (PEPRA), the state has a standard that state employees pay one-half of the normal cost of their pension benefit and the state pays one-half of the normal cost.

Unfunded Liability. When investment returns or other actuarial assumptions do not materialize (or actuarial assumptions change) such that actuaries determine there are not sufficient assets to pay for benefits earned in the past, the resulting shortfall is called the “unfunded liability.” Any unfunded liability is the employer’s responsibility.

Unit 6 Employees Hired Before 2013 Receive Pension Based on “3 Percent at 50” Formula. The pension benefits earned by state public safety employees—including Unit 6 members who earn their pension benefit under the state’s Peace Officers and Firefighters plan—are described in this publication produced by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS). Unit 6 members hired before 2013 earn a pension benefit based on what is referred to as the 3 percent at 50 formula whereby an employee earns 3 percent of their final compensation for every year of service if they retire at the age of 50 years. Under this formula, the maximum income replacement ratio a retiree may receive is 90 percent of their final compensation (defined as compensation over a 12-month period) after attaining 30 years of service credit. According to information provided by CalHR, in the five fiscal years between 2017‑18 and 2021‑22, the average Unit 6 member retired at 55 years old with 23 years of service and retired with a pension that replaced 68 percent of their final compensation.

Unit 6 Employees Hired After 2013 Receive Pension Based on “2.5 Percent at 57” Formula. Under PEPRA, employees hired after 2013 receive a lower pension benefit that require employees to work additional years in order to maintain the same level of benefit as employees who were hired before 2013. In the case of Unit 6, employees hired after 2013 earn a pension under the 2.5 percent at 57 formula. Under this formula, employees who work for 40 years and are older than 57 years may receive a pension that replaces 100 percent of their final compensation (defined as compensation over a 36-month period). However, an employee under this pension formula who retires at 55 years old with 23 years of service would be eligible for a pension that replaces 54 percent of their final compensation. In order to receive the 68 percent income replacement ratio received by average recent Unit 6 retiree, a Unit 6 member hired after 2013 would need to work until they are at least 57 years old and have 27 years of service.

Optional Employee-Funded Defined Contribution Benefit. Since 1974, the state has provided employees with an optional deferred compensation plan. The plan today is known as Savings Plus. Through Savings Plus, employees can open a 401(k) and/or a 457(b) account and can choose to make contributions on a pre-tax or post-tax basis to these accounts. Employees can then choose from a variety of investment options, including indexed and managed funds and target-date funds. The state has never made regular contributions to rank-and-file employees’ Savings Plus accounts. (CalHR informs us that the state briefly contributed a small specified dollar amount to excluded employees’ Savings Plus accounts in the early 2000s.) In 2017, we issued a report evaluating the Savings Plus program. As of May 2016, we reported that 60 percent of eligible state employees participated in the Savings Plus program. While we do not know the statewide average participation rate today, CalHR informs us that, as of July 31, 2023, 87 percent of Unit 6 members have a Savings Plus account and that 57 percent of Unit 6 members contributed to their Savings Plus account in July 2023 with an average contribution amount of $387 to a 457(b) account and $353 to a 401(k) account. Based on the data CalHR provided us, far more Unit 6 members have 457(b) accounts (20,241 members with accounts) than 401(k) accounts (4,599 members with accounts). The administration indicates that the average balances of Unit 6 457(b) and 401(k) accounts was $20,803 and $27,272, respectively.

Legislature Chose Not to Adopt Hybrid Plan When Enacting PEPRA. Under PEPRA, the Legislature established sweeping changes to state pension benefits that reduced the benefits for future employees and established a standard that state employees pay one-half of the normal cost to fund these benefits. However, the law retained the basic structure of the state’s benefit in that the employer-funded retirement income benefit consists only of a defined benefit pension. The Legislature could have adopted a hybrid plan, whereby the state contributed money to both a defined benefit and a defined contribution element of a retirement benefit, but it did not.

Proposed Agreement

Major Provisions

Term. The agreement would be in effect from July 3, 2023 through July 2, 2025. This means that the agreement would be in effect for two fiscal years: 2023‑24 and 2024‑25. This also means that the agreement will expire, and the administration presumably will begin negotiating a new MOU, before the February 1, 2026 date when Section 19826 of the Government Code requires CalHR to submit to the Legislature a new compensation study for Unit 6.

GSIs. The agreement would provide a 3 percent GSI on July 1, 2023 and another 3 percent GSI on July 1, 2024.

One-Time $1,200 Payments in 2023 and Again in 2024. The agreement would provide employees a $1,200 payment in November 2023 and another $1,200 payment in November 2024. The stated purpose of this payment is to support employees’ health and well-being. However, there is no requirement that the money be used to further this purpose.

Recruitment and Retention Payments. The agreement would provide specified payments related to recruiting and retaining employees. Specifically, new and current Unit 6 members who work at Salinas Valley State Prison (SVSP) in Soledad; California State Prison, Sacramento (SAC); or Richard J. Donovan (RJD) Correctional Facility in San Diego would be eligible to receive $5,000 payment on July 1, 2024 and another $5,000 payment on July 1, 2025. In addition, cadets who accept or choose to work at one of 13 facilities would be eligible to receive a $5,000 bonus payment payable in two payments ($2,500 upon graduating from the academy and $2,500 30 days after reporting to the institution).

Creation of Employer Funded Contributions to 401(k). Effective with the November 2024 pay period, the agreement would provide that the state make a one-time contribution of $475 to a Savings Plus 401(k) plan on behalf of all permanent full-time employees who are active as of November 1, 2024. Effective with the January 2025 period, the agreement would require the state to make a monthly contribution equivalent to 1 percent of base pay to a Savings Plus 401(k) plan.

State Contributions to Health Premiums. The agreement would increase state contributions towards employee health benefits to maintain the current proportion of average premiums paid by the state.

Increased Pay Differentials. The agreement would increase various Unit 6 pay differentials, including the night/evening shift differential, weekend shift differential, and bilingual pay differential.

One-Time Leave Cash Out. Under the proposed agreement, all Unit 6 member would be eligible to cash out up to 80 hours of compensable leave in 2023. The administration estimates that this provision could increase state costs by as much as $25 million. The actual cost will depend on how many employees cash out leave and how much leave they choose to cash out.

Provisions From Past Agreements Not Included

No Reopener if Other Units Get Higher Pay Increases. The expired Unit 6 MOU included a provision that specified that CCPOA could choose to reopen that agreement if another bargaining were to have received a higher GSI in 2022‑23. As we discussed in our August 2022 analysis of the Unit 2 agreement at the time, that particular reopener clause seemed to affect the administration’s negotiating position with other bargaining units in that none of the agreements provided GSIs higher than the Unit 6 GSI in 2022‑23. The proposed agreement does not appear to includes a similar reopener clause.

No Provision Related to Compensation Study. The proposed agreement deletes Article 15.19 from the agreement. This means that the proposed agreement includes no language related to the Unit 6 compensation study or to Section 19286 of the Government Code. The administration states that it will use the same methodology in future Unit 6 compensations studies that it used for the 2022 compensations study.

LAO Assessment

2018 Compensation Study

Disagree That 2018 Compensation Study Is Confidential Under CPRA. We disagree with the administration’s assertion that the 2018 compensation study and all information related to it are confidential under the CPRA. The language of Article 15.19 clearly stated that the JLMC process would occur before CalHR conducted its compensations study when it said that the parties would discuss the criteria, comparators, and methodology to be utilized. Further, Article 15.19 states that the compensation study completed after the JLMC process would be “created pursuant to Government Code Section 19826.” Under Section 19826 of the Government Code, CalHR is the sole author of the compensation study as the study is to report to the union and Legislature “the department’s findings.” We would argue that the language of Article 15.19 does not make the compensation study itself a product of the JLMC process—only the discussion of the methodology. As such, when CalHR submitted the compensation study to CCPOA it also should have submitted it to the Legislature.

CPRA Issue Raises Broader Questions About JLMC Work and Legislative Deliberation. Most, if not all, MOUs include at least one JLMC or similar management/labor workgroup. These workgroups can be tasked with discussing a wide array of topics. Often, the topics of these workgroups are meant to be the initial assessment of whether something is feasible. For example, an MOU might establish a JLMC to assess the feasibility of consolidating classifications. In these cases, the working group often submits a report to specified individuals (typically, the Director of CalHR) with the group’s recommendations, but the actual process of consolidating classifications is left to the State Personnel Board process and the Legislature’s budget review process (in the case of class consolidations that require appropriations). In these cases, there is an opportunity for the public and the Legislature to weigh in on the issue under consideration by the JLMC. However, as the 2018 compensation study reveals, there also are instances where the JLMC may influence state policy without legislative insight. This is because the JLMC process generally is excluded from public disclosure under the CPRA. Consequently, unless there is a separate policymaking process—like in the example regarding classification consolidation—the administration may propose policy changes without sufficient justification. As the administration does not offer justifications for things that are the product of the bargaining table, neither the Legislature nor the public may have sufficient information to weigh the rationale for the proposed policy change.

2022 Unit 6 Compensation Study

Study Flawed

As we discuss below, the study is flawed to the point that it is not helpful in meeting its stated objective and we recommend policymakers not use it to assess whether the state’s compensation package for correctional officers is appropriate to attract and retain qualified workers. On the whole, the issues we discuss below likely result in overstating competitor employer’s total compensation while understating the state’s total compensation; however, the flaws in the study raise so much uncertainty that we cannot say that definitively.

Issues With Comparators and Survey Sample

Study Omits Overtime, a Substantial Component of Compensation. Overtime has long constituted a significant source of income for Unit 6 members. CalHR’s 2013 Unit 6 compensation study included overtime in its analysis and identified that the average Unit 6 member earned overtime pay equivalent to 15 percent of their wages. Overtime continues to be a major source of income for state correctional officers. In 2022, Unit 6 members earned $547.8 million in overtime payments and $2.2 billion in gross regular pay. This means that overtime payments in 2022 were equivalent to roughly 24 percent of gross regular pay for Unit 6 members. Overtime was excluded from CalHR’s 2022 compensation study analysis despite (1) overtime consistently being a major component of Unit 6 compensation and (2) CalHR including overtime in its 2013 Unit 6 compensation study and in its recent compensation studies of most other bargaining units.

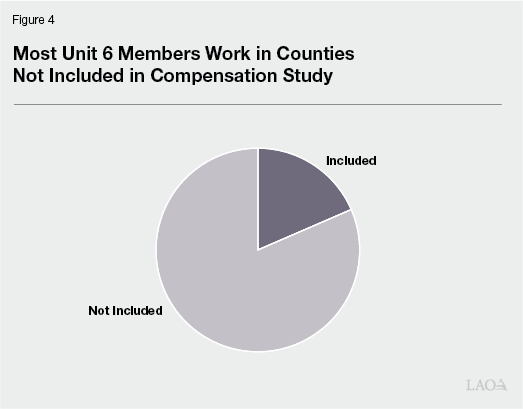

Survey Sample Not Representative of Where State Correctional Officers Work… The compensation study surveyed the six counties that employ the most peace officers in the state. This methodology results in a sample consisting mostly of counties that are part of large metropolitan regions in the state. In contrast, most state prisons are located in rural parts of the state located far from major urban centers. As a result, the six counties surveyed for the compensation study are not representative of where state correctional officers work. While some state correctional officers work in four of the counties included in the survey, there are zero state correctional officers who work in the Counties of Orange or Santa Clara. Thus, one-third of the compensation comparison in the study is not actually directly competing with the state for workers.

As Figure 4 shows, only 18 percent of Unit 6 members work in one of the six counties included in the survey. If, instead, the survey was based on the six counties where the most Unit 6 members work—the Counties of Kern, Kings, Riverside, Solano, Monterey, and Sacramento—the study would have included counties where more than 50 percent of Unit 6 members work. (If the survey only included the two counties where the highest numbers of Unit 6 members work, the Counties of Kern and Kings, the sample would have been more representative than the sample used by the administration as more than 25 percent of Unit 6 members work in one of those two counties.)

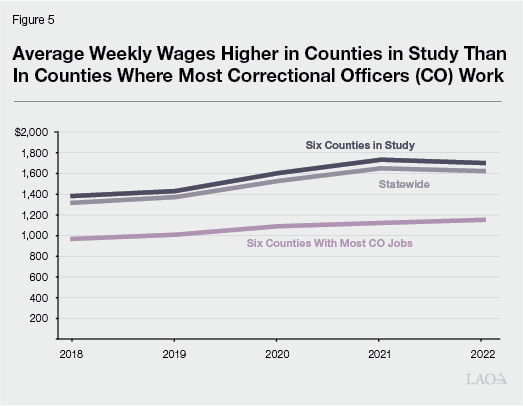

…Reflects Regions With Much Higher Wages and Cost of Living Than Where Correctional Officers Work. Wages and the cost of living vary significantly across the state. As Figure 5 shows, the six counties in the study have average wages that are somewhat higher than the statewide average and far above average wages in the six counties with the highest concentration of Unit 6 worksites (the Counties of Kern, Kings, Riverside, Solano, Monterey, and Sacramento). This means that the study includes counties in the state with substantially higher wages than where most state correctional officers work. Furthermore, as Figure 6 shows, the six counties in the study have far higher housing costs (a major component of the cost of living) than the six counties with the highest concentration of Unit 6 worksites.

Issues With Treatment of Retirement Benefits

Study Uses Wrong Measure to Compare Pension Benefits. Using the total employer contribution rate towards pension benefits is problematic when trying to evaluate the value of the pension benefit earned by employees today. This is because the total contribution rate paid by employers (1) might include a single blended contribution rate towards normal cost and not distinguish between the value of benefits earned by different employees in the same classification, as is the case with at least the state; (2) includes payments towards unfunded liabilities that reflect costs associated with pension benefits earned in the past and that are affected by decisions made by employers (for example, making supplemental pension payments) or pension boards (for example, assumed rates of return on investments not be realized) that are not related to the benefit earned by employees today; and (3) does not capture any employer cost to the benefit that is excluded from the contribution rate (for example, supplemental pension payments in excess of the contribution rate). The normal cost is driven by (1) the design of the pension benefit (in other words, the terms of the benefit) and (2) the actuarial assumptions used to calculate normal cost. While different pension systems might use different assumptions—for example, different assumptions related to future investment returns—that affect the normal cost, they also have different policies—for example, different mixes of asset classes in their investment portfolios. A pension board has a fiduciary responsibility to use actuarially sound assumptions consistent with its policies when determining employer contribution rates. As such, the normal cost for the benefit earned by employees is the best estimate of the value of the employer-provided benefits earned today by employees and therefore the best way to compare pension benefits across employers. We discuss the specifics of the methodological issues related to pension benefits in the subsequent paragraphs.

Study Includes Employer Payments Towards Unfunded Liabilities to Value Pension Benefits… As we discussed above, employers and employees each make contributions towards the normal cost of a pension benefit. However, the unfunded liability is the employer’s responsibility. In addition to experience (for example, lower-than-assumed investment returns) and assumption changes, employers’ actions also can increase or decrease unfunded liabilities. For example, an employer choosing to make supplemental pension payments—meaning they pay more than actuaries say is necessary—will directly reduce their unfunded liability with no effect on the benefit provided to employees. When conducting compensation studies, including the 2022 Unit 6 study, it is CalHR’s practice to include the total employer contribution rate (expressed as a percentage of pay) paid by employers to fund employees’ pension benefits. This total contribution rate includes employers’ costs to both the normal cost and unfunded liabilities when determining the value of employees’ pension benefits. This means that the study reflects the cost both for pension benefits earned today as well as for pension benefits earned in the past.

…Assumes Same Employer Contribution Rate for Entry-Level and Journey-Level State Correctional Officers Despite Very Different Benefits… Under PEPRA, as we discussed above, state correctional officers hired after 2013 receive a lower benefit than employees hired before that date. To make state payroll less complicated, CalPERS provides the state one employer contribution rate that the state pays, regardless of which benefit an employee earns, that is based on a blended normal cost. The compensation study uses this blended employer rate to value the pension benefits earned by newer state hires and journey-level state correctional officers. As such, the study assumes that the value of both pension benefits is equivalent to 32.84 percent of pay (19.14 percent of this is the employer’s share of the blended normal cost). This results in the study undervaluing the benefit earned by journey-level state correctional officers and overvaluing the benefit earned by entry-level employees. If the study had, instead, used the unblended employer share of normal cost to value the pension benefits earned by state correctional officers, the study would have assumed that entry level state correctional officer pension benefits were equivalent to 15.1 percent of pay and journey-level state correctional officer pension benefits were equivalent to 22.1 percent of pay. (We note that the study also assumes that the County of Santa Clara pays the same contribution rate for both entry-level and journey-level employees.)

…And Uses Data From Year When State Contributions to Unfunded Liability Was Temporarily Low, Distorting State’s Pension Benefit to Appear Less Valuable Overall. In recent years, the state has made a number of supplemental pension payments to CalPERS. These payments are in addition to the payments CalPERS identifies the state must pay pursuant to state law and go directly towards paying down the state’s unfunded liability. (In addition, it is the state’s policy to apply the Proposition 2 debt repayments towards the CalPERS unfunded liabilities.) As we describe in The 2020‑21 Spending Plan: Pensions, the 2019‑20 budget plan included a $2.5 billion supplemental pension payment to CalPERS to reduce the state’s long-term unfunded liabilities; however, the 2020‑21 budget repurposed this supplemental pension payment to instead supplant the state’s actuarially required contributions over a multiyear period beginning in 2020‑21 (due to anticipated budget shortfalls). This action resulted in the portion of the state’s contribution rate that goes towards the unfunded liability to be lower than it otherwise would have been in 2021‑22, the year from which data was pulled for the compensation study. To illustrate the temporary effect this had on the state’s contribution rates, this action resulted in the state’s contributions to Unit 6 members’ pensions to total 32.84 percent of pay in 2021‑22, but the rate is 50 percent of pay in 2023‑24 (after the supplanting payment ended).

Study Treats Retirement Health and Retirement Pension Benefits Inconsistently. The state pays for retiree health benefits differently from how it pays for pension benefits. In the case of retiree health benefits, the state pays a percentage of pay towards normal cost (specified in labor agreements and matched by employees) to prefund the benefit and it pays the unfunded liability on a “pay-as-you-go” basis where it pays out the claims cost for existing retirees. (The state has a significant unfunded liability associated with retiree health benefits. The most recent valuation of the benefit estimates the portion of the unfunded liability associated with Unit 6 to be about $10 billion.) Unlike its treatment of pensions, the compensation study does not include any portion of the state’s payments towards retiree health unfunded liabilities. As we indicated above, we think it is better practice to only include the normal cost when trying to value a retirement benefit; however, a compensation study also should be consistent. Had the compensation study been consistent with how it valued retirement benefits, it would have included both the state’s contribution to Unit 6 normal cost ($136 million) and the state’s payments towards Unit 6 retirees’ claims ($471 million) that constitute the state’s payments towards the unfunded liability.

Study Does Not Accurately Reflect Value of Retiree Health Benefits Provided by County Employers. The study indicates that all of the surveyed jurisdictions offer an employer-subsidized retiree health benefit or some form of a retiree health savings or reimbursement account. However, to establish a value for the benefit, CalHR only asked the employers if employers made prefunding contributions towards the benefit. The state only recently began prefunding retiree health benefits. Many local governments still do not prefund the benefit and, instead, make payments on a pay-as-you-go basis after an employee retires. Of the six counties included in the survey, only two indicated that they make contributions towards the benefit during employees’ careers (the Counties of Sacramento and San Bernardino). Accordingly, the study does not attribute any value to retiree health benefits and undervalues the total compensation earned by employees of the Counties of Los Angeles, Orange, Santa Clara, and San Diego.

Study Does Not Accurately Reflect Value of State Retiree Health Benefit. Following the 2015‑16 budget, the state established lower retiree health benefits for all future state employees in MOUs. For Unit 6, the arrangement was established in the MOU that was ratified in 2016, reducing the benefit for employees hired after 2017. Per the Unit 6 MOU, the state and all Unit 6 members each pay 4 percent of pay to prefund the benefit, which is roughly one-half of the total normal cost for the benefit earned by employees hired before 2017. The compensation study uses the state’s 4 percent of pay contribution for both entry-level and journey-level employees, ascribing the same value to the retiree health benefit to all Unit 6 members. The state’s actuarial valuation of retiree health benefits calculates the total normal cost of the benefit for each bargaining unit. The valuation does not provide separate normal costs for the benefit for employee hired before 2017 versus those hired after 2017; however, the normal cost for the benefit earned by new employees certainly is lower than the normal cost for the benefit earned by employees hired before 2017. Accordingly, the compensation study overvalues the retiree health benefit earned by entry-level state employees and undervalues the retiree health benefit earned by journey-level state employees.

Overall, Reliance on Employer Cost to Estimate Value of Benefit Distorts Findings. While comparing employers’ costs to provide compensation to employees makes the survey easier to administer and complete, the comparisons can be inaccurate, particularly in the case of retirement benefits. In addition, this methodology also ignores any deductions that might be made from employees’ pay—reducing their salaries—to support the benefits provided to them as part of their total compensation. For example, the study does not capture the effect on employees’ pay when they are required to contribute a portion of their salary to prefund a retirement benefit. Employee contributions towards benefits directly reduce their pay. If two employees have identical compensation packages except one is required to contribute 4 percent of pay to prefund retiree health benefits while another does not, that contribution requirement lowers the employee’s pay, resulting in the employee who is required to contribute towards the benefits receiving a lower total compensation than the other employee. To accurately assess the relative attractiveness of employers’ supplied compensation packages to workers in the labor market, a study should sum the total pay (including overtime, scheduled pay differentials, or other payments in addition to base pay), total insurance premiums (health, dental, and vision), and total normal cost of retirement benefits (pension and retiree health) and subtract from that the deductions from pay that employees make towards premiums and normal cost of retirement benefits.

Study Not Helpful

For the reasons described above, we find that CalHR’s 2022 Unit 6 compensation study is not helpful in assessing how the state’s total compensation for state correctional officers compares with the six counties included in the study. Further, because the six counties included in the study are not representative of where state correctional officers work and, instead, includes among the highest cost of living regions of the state, we conclude that the study is not helpful in assessing the state’s position as an employer of correctional officers across the state or where state correctional officers work. We recommend the 2022 study not be used to evaluate whether or not the state’s compensation for correctional officers is competitive.

Legislative Oversight

Legislative Oversight of State Compensation Policies Key to Effective Oversight of State Spending. State employee compensation is a significant portion of the cost of state government operations, totaling more than $30 billion (roughly one-half of which is paid from the General Fund). In addition, the state has significant unfunded liabilities associated with retirement benefits for state employees’ and retirees’ past service (in excess of $70 billion for pensions and $95 billion for retiree health benefits). Changes in employee compensation policies can have profound effects on the state’s expenditures and long-term plans to address unfunded liabilities. As such, the Legislature’s ability to exercise a high degree of oversight over the state’s employee compensation policies is critical.

Compensation Studies Helpful Tool to Evaluate Proposed Compensation Policies. The Legislature regularly considers changes to state employee compensation policies through the policy bill process, the budget bill process, and through its role in considering labor agreements reached between the administration and state bargaining units. A regularly occurring, well-designed, and well-executed compensation study helps provide the Legislature a baseline from which to assess (1) the state’s current position as an employer in the labor market and (2) the effect that any proposed employee compensation policy might have on the state’s position as an employer.

Regular Total Compensation Studies Should Not Be Subject of Bargaining Process. A compensations study should present a set of facts identified using a transparent methodology that can serve as a starting point in negotiations. A compensation study, itself, should not be the subject of negotiations. If a bargaining unit disagrees with the methodology or findings of a CalHR compensation study, it can pay for its own compensation study to be conducted by a third party. (We note that Unit 2 [Attorneys] contracted with the University of California at Los Angeles to conduct a study leading up to the 2019 MOU.) Allowing compensations studies to be the subject of bargaining (1) opens the door to inconsistent methodologies used to assess different bargaining units’ compensation, which, in turn, makes compensations studies less helpful in identifying internal equity issues across bargaining units and (2) allows issues at the bargaining table to prevent a compensation study from being submitted to the Legislature.

Unit 6 Compensation

Given the shortcomings of the 2022 compensation study, we look to other metrics to assess the state’s ability to recruit and retain correctional officers. We discuss those factors below. On the whole, we see little evidence to suggest that the state’s ability to recruit and retain correctional officers has deteriorated such that the state is not an employer of choice for correctional officers in California.

Inflation and Unit 6

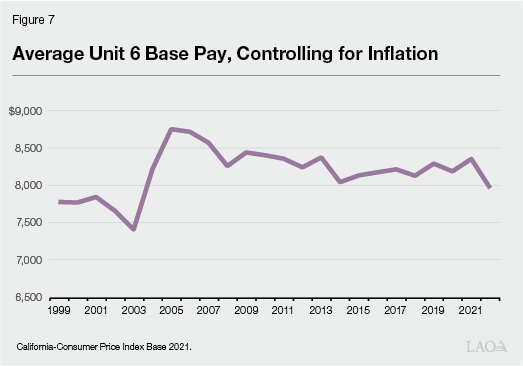

Unit 6 Base Pay Has Not Kept Pace With Inflation, but Well Above Pre-2006 Levels. As we discussed in our 2008 analysis, CDCR experienced high vacancies and recruitment challenges for correctional officers in the early 2000s that were addressed through operational changes as well as significant increases to correctional officer compensation provided by the Unit 6 MOU that was in effect from 2001 to 2006. At the time, we indicated that “the job of state correctional officer may now be the most sought after in the California economy” thanks to the increase in compensation. Controlling for inflation, Figure 7 shows that average Unit 6 base pay increased by 18 percent between 2003 and 2006 under the terms of the 2001‑06 MOU. Since 2006, inflation has eroded the average Unit 6 base pay such that real base pay in 2022 was almost 9 percent lower than it was in 2006. However, average real base pay remains more than 7 percent higher than it was in the early 2000s when the state last experienced significant challenges recruiting correctional officers. (As we discuss below, turnover may be contributing to the decline in the average base pay. With an increase in retirements in recent years—and an increase in new officers—average base pay declines reflect the lower tenure of staff as well to some extent.)

Proposed GSIs Close to Most Recent Inflation Levels. The most recent (July) California Consumer Price Index was 3.1 percent higher compared to the prior year. Since 2020, however, prices have risen 17 percent. GSIs provided by prior agreements to Unit 6 did not keep pace with these increases, as noted above. Although the tentative agreement’s GSIs would maintain wages, they do not catch up to prior price increases.

Recruitment and Retention of State Correctional Officers

Use 2013 Compensation Study as Benchmark. Although not perfect, the 2013 compensation study had far fewer methodological flaws than the 2022 compensation study. Consequently, we use the 2013 study as our benchmark and look at recruitment and retention patterns to assess if the state’s position in the labor market to attract and retain qualified employees has deteriorated significantly since 2013, when CalHR found that state correctional officers were compensated well above local government counterparts.

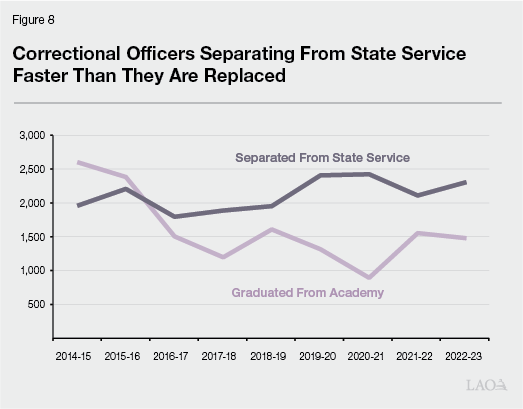

Number of Unit 6 Members in Decline. As we discussed earlier, state policy has changed in recent years to result in a decline in the state correctional population (including people in prison, and on parole) and the closure of state prison facilities. This trend has resulted in the number of Unit 6 members to decrease over the years. The number of Unit 6 members reached a high-water mark of over 32,500 members around 2008 and has steadily declined since then with 26,000 members in 2013 and fewer than 24,500 members in 2022. This also is illustrated by the fact that, as Figure 8 shows, fewer correctional officers are graduating from the academy and entering the workforce than are separating from state service.

Fewer Vacant Correctional Officer Positions Today Than in 2013. The reduction in the number of state correctional officers is the result of changes in state policy and does not appear to be due to challenges in filling established positions. Compared with the time of the last compensation study, the share of state correctional officer positions that are vacant has decreased from 14.5 percent in January 2014 to 12.1 percent in January 2022. On one hand, this suggests that CDCR is not experiencing greater challenges recruiting and retaining correctional officers than in 2013. On the other hand, prison closures have resulted in a substantial reduction in the number of state positions. With fewer authorized positions, we would expect the vacancy rate to decrease. The fact that the vacancy rate has only dropped 2 percentage points might signal a recruitment or retention problem, however, as we discuss below, there are indicators pointing the other way as well. (Moreover, Unit 6 is unique in that its vacancy rate is declining, whereas for almost all other bargaining units, the vacancy rate has increased in recent years.)

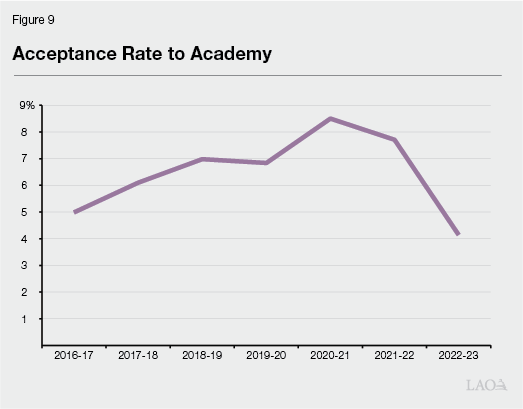

Correctional Officer Academy Turns Away More Than 90 Percent of Qualified Applicants. The job of state correctional officer consistently is a sought-after job. Between 2013‑14 and 2022‑23, CDCR received 372,998 applications to the correctional officer academy. Of these applications, 292,488 applications were from applicants who met the minimum qualifications. During this same time period, the department accepted 17,530 applicants into the academy. This means that CDCR accepted about 6 percent of qualified applicants to enroll in the academy to receive training to become a correctional officer. Among all applications, qualified and not qualified, CDCR accepted about 5 percent of applicants. (For context, the academy for the California Highway Patrol accepted 4 percent of qualified applicants in 2022‑23.) Figure 9 shows how the acceptance rate has fluctuated since 2016-17. There clearly is very high interest among people to become state correctional officers. The high level of interest in the job despite its challenging working conditions likely reflects that, compared with other jobs that have similar education requirements, the state provides correctional officers competitive salaries and benefits as well as job security.

Evidence of Turnover Among Staff. There is some evidence that there has been elevated turnover among correctional officers since 2013 where more senior employees are being replaced by less experienced employees. While the factors that we discuss below show that the bargaining unit is becoming younger and less experienced, the average correctional officer continues to be a mid-career correctional officer with more than a decade of experience. This suggests that the younger workforce might not be an indication of a problem, but rather natural turnover as employees retire.

Fewer Years of Service Among Staff. The average Unit 6 member in 2022 had 11.4 years of service. This is about one year fewer years of service than the average Unit 6 member had in 2012. However, the average Unit 6 member has about one more year of service than they did in 2008 when the average Unit 6 member had 10.4 years of service.

Fewer Employees at Top Step. The share of Unit 6 members who are at the top step of the correctional officer salary range has decreased from 71 percent in 2013 to 57 percent in 2021. This is consistent with the fact that state correctional officers tend to have fewer years of service today than they did in 2013.

Younger Workers. Over the past ten years, the average Unit 6 member has become younger. The share of Unit 6 members who are 40 years old or younger has increased 10 percentage points form 42 percent in 2012 to 52 percent in 2022. The fastest growing age group during this period was 26 to 30 years old.

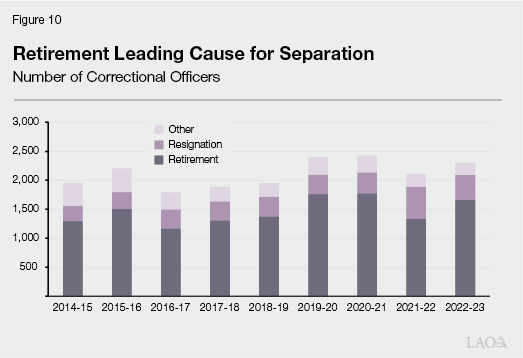

Any Retention Issues Likely More Attributable to Factors Other Than Compensation. The turnover of state correctional officers in recent years likely is due to factors other than compensation. Figure 10 shows that separations have been driven primarily by retirements; however, there was a notable increase in the number of resignations in 2021‑22. When a person resigns, they voluntarily end their employment without going into retirement. The person might seek employment with a different employer doing the same job, change careers, or exit the workforce. If a person is dissatisfied with their job or with the level of compensation they receive for their job, they are more likely to resign. As such, a spike in resignations warrants further investigation to understand the root cause of the resignations. As we discuss below, we do not think that compensation has been the main driver leading to increased retirements and a spike in resignations.

Aging Cohort of Correctional Officers Driving Retirements. The average correctional officer retires at the age of 55 years after having worked for the state for 23 years—this statistic is unchanged from 2013. This means that the average retiring correctional officer was hired at the age of 32 years. In the early and mid-2000s, the state hired a large number of new correctional officers. This created a cohort of correctional officers of a similar age. As this cohort, and the officers hired before this cohort, became eligible for retirement, they have retired and have been replaced by new, younger correctional officers. The growth in retirements that CDCR has experienced in recent years likely is due more to the natural aging of the workforce rather than a response to Unit 6 compensation levels.

Pandemic. The time period from March 2020 through September 2022 was a particularly turbulent time for state prisons. The weekly cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 in state prisons was far above levels seen in California broadly during each of the waves of the pandemic. The threat to the health and safety of both people living in prisons and working in prisons resulted in the administration implementing a number of personnel policies related to staff testing for the virus, mask wearing, and vaccination. Both the health risk itself and the administration’s policies to address the health emergency may have driven the spike in resignations that occurred in 2021‑22 and could have been a contributing factor for eligible employees to decide to retire.

Female Correctional Officers

2018 State Law Limits Use of Male Officers at Female Institutions. In 2018, the Legislature approved and the Governor signed Chapter 174 (AB 2550, Weber), adding Section 2644 of the Penal Code. This law seeks to protect females in prison from sexual assault, abuse, and other improper contact with male correctional officers. Specifically, the law prohibits—except in specified emergency situations—male correctional officers from (1) conducting a pat down search of females in custody, (2) entering an area inside the prison where females may be in a state of undress, or (3) being in an area where they can view females in custody in a state of undress.

Few Female Correctional Officers. The profession of correctional officer historically has been dominated by men. Since 2003, the share of Unit 6 members who are women has steadily declined. Specifically, whereas 21 percent of Unit 6 members were women in 2003, 17 percent of Unit 6 members were women in 2022. As we said in 2019 when we reviewed the Unit 6 MOU submitted for ratification that year, CDCR might need to recruit additional women correctional officers to work in its women’s prisons to maintain compliance with Section 2644.

2019 MOU Established Working Group to Develop Recruitment Strategies for Female Staff. The 2019 MOU included a provision that established a working group to develop strategies to enhance recruitment, transfer, and retention of female staff at women’s prisons. We asked CDCR to provide an update to us on the outcome of this working group. The department informed us that (1) the working group did not meet and, consequently, did not produce any strategies to improve recruitment and retention of female staff but (2) the department independently has implemented strategies. The strategies that CDCR indicated it has implemented to improve recruitment and retention of women include targeted marketing; development of a website focused on women in CDCR; using women recruiters and ambassadors at recruitment events; recruiting at women-focused events (for example, the Central Valley Women’s Conference); partnering with women-focused organizations (for example, women’s athletics programs); and attending national and state women’s conferences to learn new strategies to attract women applicants. Lastly, CDCR indicated that it signed onto the 30x30 pledge to improve the representation of women in police recruits to 30 percent by 2030.

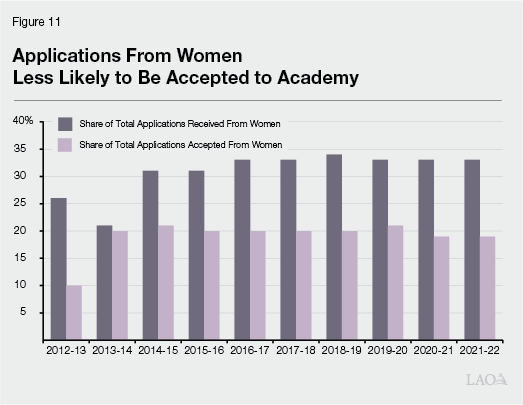

Women Disproportionately Rejected From Academy Application Process. Part of the challenge of hiring female correctional officers is due to the fact that more men apply to become correctional officers than women. For example, since 2011‑12, men consistently have made up more than 66 percent of the applications received for the academy with the highest share being in 2011‑12 when 82 percent of the applications were from men. In addition, however, something in the application screening process results in applications from women being more likely to be rejected. Specifically, as Figure 11 shows, in all of the past ten years, women have represented a smaller share of the number of people admitted to the academy than they did the share of people applying for a position in the academy. As long as this trend continues, the share of female correctional officers likely will continue to decline and put at risk CDCR’s compliance with Section 2644. CDCR indicated that one reason that women have been dropped out of the application process in the past is because women were more likely to fail the Physical Fitness Test element of the application process where applicants are required to carry weights in varying size to specific distances to simulate carrying a stretcher during an emergency. The department informs us that, as of March 2023, the Physical Fitness Test has been removed from the applicant selection process; however, all cadets will still be required to pass the Physical Fitness Test at the academy, but can do so in an environment where they can learn and be mentored in developing the skills needed to pass the course. This could result in fewer female applicants being rejected from the academy.

The Proposed Agreement

Changes to Retirement Benefits Established by PEPRA

Agreement Fundamentally Enhances Unit 6 Retirement Benefit. The agreement would change the employer-funded retirement income benefit for Unit 6 members from a defined benefit pension to a parallel hybrid plan whereby the state funds both a defined benefit pension and a defined contribution plan. This fundamentally changes the state’s retirement benefit. Such a change warrants serious and extensive deliberation to work through issues and questions like those below.

What Problem Is The Proposal Trying to Address? The defined benefit pension provided to new and senior Unit 6 members provides a substantial income replacement ratio that allows the average retiring Unit 6 members to replace nearly 70 of their income without regard to any personal savings or assets available to the retiree. A new employee only needs to work four years longer than more tenured employees to receive the same level of benefit.

With a New Employer-Funded Defined Contribution Component, Should the Employer-Funded Defined Benefit Component Decrease? Hybrid pension plans where employees earn both an employer-funded defined benefit pension and an employer-funded defined contribution plan typically include a somewhat less generous defined benefit than employers who provide only a defined benefit pension.

Does Establishing a Hybrid Retirement Plan for Unit 6 Raise Equity or Parity Issues With Other Bargaining Units? The state’s pension benefit is largely consistent across bargaining units by providing a defined benefit pension that offers different income replacement levels depending on date of hire, whether an employee is in Social Security, and the employee’s job. With an average base pay of over $95,500, Unit 6 is not a low-income bargaining unit. In contrast, the average base pay for Unit 15 is about $45,000. As we indicated earlier, lower-income people typically need a higher income replacement ratio in retirement as a larger share of their income goes towards basic needs.

Should There Be a Vesting Requirement for the State’s Contribution? Employers generally can establish vesting requirements that require employees to work for a specified amount of time before the employee has a right to employer contributions made to a 401(k).

With a Larger Share of Unit 6 Utilizing Savings Plus 457(b) Plans, Why Require the Employer Contribution to Go to a 401(k)? Employees must pay Savings Plus maintenance fees for each account they hold. An employee might want to minimize these fees by maintaining only one account. With 85 percent of Unit 6 members participating in a Savings Plus 457(b) plan (compared with 19 percent in the 401[k] plan), it would make sense to give employees an option to have the state’s contribution go towards a 457(b) plan.

Location-Specific Bonuses

Administration Gives No Supporting Evidence That Three Institutions Are “Hard to Fill.” The agreement identifies SVSP, SAC, and RJD as hard to fill. The administration provides no evidence or justification to support this claim. Vacancy rates of the institutions do not support the claims. All three facilities have lower-than-average vacancy rates of correctional officer positions with 11 percent, 11 percent, and 9 percent vacancy rates, respectively, in January 2022.

Administration Provides No Justification to Create Incentive Payments for New Officers to Go to Specified Institutions. The administration provides no evidence or justification to suggest that the incentive payments for new officers at specified facilities are necessary to maintain an inflow of new recruits to those institutions. The list of institutions includes seven of the facilities with the most Unit 6 positions (Kern Valley State Prison in Delano; SVP; San Quentin Rehabilitation Center; Substance Abuse Treatment Facility and State Prison in Corcoran; California Health Care Facility in Stockton; RJD; and California State Prison, Corcoran). However, it is not clear that these institutions are less desirable work sites for new recruits than other institutions. Vacancy data would seem to support including Pelican Bay State Prison in Crescent City (with a 28 percent vacancy rate), but several of the other institutions included on the list have vacancy rates quite a bit lower than the average vacancy rate for correctional officers across the department

Fiscal Effect

Agreement Will Contribute to Rising Costs to Run Prisons. As Figure 12 shows, the administration estimates that the agreement would increase the state’s annual costs by more than $410 million General Fund. If the provisions of the agreement were extended to excluded employees affiliated with Unit 6 (generally, managers and supervisors), the administration estimates that the state’s annual costs would be nearly $50 million more. This is a significant effect on the state’s finances. A number of members of the Legislature regularly express concerns about the rising cost to administer state prisons. If ratified, relative to the CDCR operational spending assumed in the budget in 2023‑24, the agreement would increase the cost to run state prisons by nearly 3 percent.

Figure 12

Administration’s Estimated Fiscal Effect of Proposed Unit 6 Agreement

(In Millions)

|

2023-24 |

2024-25 |

||||

|

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

||

|

General Salary Increases |

$127.4 |

$127.4 |

$258.5 |

$258.5 |

|

|

Health Benefits |

16.9 |

16.9 |

45.4 |

45.4 |

|

|

Pay Differentials |

27.9 |

27.9 |

37.2 |

37.2 |

|

|

One-Time $1,200 Payments |

29.5 |

29.5 |

29.5 |

29.5 |

|

|

Employer Contributions to 401(k) |

— |

— |

22.9 |

22.9 |

|

|

Recruitment and Retention Payments |

3.3 |

3.3 |

16.3 |

16.3 |

|

|

Other Provisionsa |

1.3 |

1.3 |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

|

One-Time Leave Cash Out |

25.2 |

25.2 |

— |

— |

|

|

Totals |

$231.5 |

$231.5 |

$411.8 |

$411.8 |

|

|

aAdministration assumes that a portion of these costs would not require additional appropriations from the Legislature. |

|||||

Legislature’s Role in Bargaining Process

Legislature Is Ultimate Authority of Any Labor Agreement. Under the Ralph C. Dills Act, while the Governor negotiates terms and conditions of employment with bargaining units, the Legislature retains the ultimate authority to approve or reject agreements. The Legislature can reject an agreement either by (1) rejecting a tentative agreement that is submitted to the Legislature for ratification or (2) not appropriating sufficient funds to pay for the terms of an MOU that the Legislature has already ratified.

Administration’s Delivery of Agreement Does Not Allow for Sufficient Time for Legislative or Public Review. The administration submitted this agreement to the Legislature three days before the budget committees heard the agreement. Giving the Legislature such a constrained review period to review a proposal with such significant fiscal and policy implications is inappropriate. The public—including the members of the bargaining unit—also should have a greater opportunity to review the provisions of the agreement and provide input to the Legislature.

Budget Change Proposals of Far Smaller Size Would Require Justification From Administration, Legislative Deliberation, and Public Scrutiny. If ratified, the agreement will increase state costs by hundreds of millions of dollars each year. When budget proposals of far lesser value are submitted to the Legislature by the Governor during the budget process, they are subject to public and legislative review for a period of weeks or months, not days.

LAO Recommendations

Review How to Improve Access to Collective Bargaining Information. In order to improve legislative oversight of the state’s employee compensation policies, we recommend that the Legislature review how it can gain better access to information discussed through the collective bargaining process. In particular, when future agreements establish JLMC processes, we recommend that the Legislature seek clarification as to (1) what information the parties will share with the Legislature and (2) when such information might be shared with the Legislature.

Establish Consistent Requirements for Compensation Studies of All Bargaining Units. While the compensation study that CalHR produces for other bargaining units is not perfect, it is helpful for understanding how the state’s total compensation compares with that provided by other employers to similar employees across California. In contrast, compensation studies that look at only a small handful of select and unrepresentative samples—like Unit 6 as well as the annual salary survey of Unit 5—are not helpful in understanding whether the state’s compensation policies are competitive. While there can be separate unit-specific salary surveys or other compensation studies, we recommend that the state’s regular total compensation report established in Section 19826 of the Government Code use a consistent methodology that allows for the Legislature to have better oversight of the workforce and the state’s compensation policies.

Consider Utilizing Third Party to Conduct Compensation Studies on Scheduled Basis Independent of Bargaining Cycle. We recommend that the Legislature consider removing from CalHR the responsibility of conducting the state’s regular total compensation studies and, instead, consider directing CalHR to contract out this responsibility to a third party that is independent from the collective bargaining process. For example, the state could contract with the University of California, like Unit 2 did in the past, to conduct the review.