February 27, 2025

The 2025-26 Budget

University of California

Summary

Brief Covers the University of California (UC). This brief analyzes the state’s budget plan relating to UC’s core operations and enrollment. Under the 2025‑26 budget plan, UC receives $10.8 billion in total core funding. Of this amount, 53 percent comes from tuition and fee revenue ($5.7 billion), 43 percent comes from state General Fund ($4.6 billion), and the remainder comes from various other sources.

Under Plan, State Support for UC Declines but Tuition Revenue Increases. The budget plan includes a $272 million ongoing General Fund reduction for UC in 2025‑26. This reduction is mostly offset by a projected $241 million increase in student tuition and fee revenue (due to higher tuition charges and planned enrollment growth). After accounting for these changes, total ongoing core funding for UC would decrease by $30 million (0.3 percent).

Budget Plan Also Includes Funding Deferrals. The administration has a compact with UC’s President to provide UC with 5 percent annual base increases, as well as ongoing General Fund support to replace nonresident students with resident students at three high‑demand campuses, from 2022‑23 through 2026‑27. The state budget plan, however, defers the 2025‑26 base increase ($241 million) and nonresident replacement funding ($31 million) until 2027‑28. As part of the deferral arrangement, the state would plan to provide UC with one‑time back payments in 2026‑27 and 2027‑28.

UC’s Spending Priorities Exceed Available Funding. UC’s 2025‑26 spending plan identifies over $500 million in new expenditures (with 30 percent identified as nondiscretionary). In response to the state budget plan, UC has begun making budget adjustments, including implementing hiring freezes and reducing nonessential expenditures. Though UC does not yet know how it would respond to the deferrals, it would face more disruptive budget adjustments if it increased spending in 2025‑26 and then the deferred payments were eliminated or postponed. The state has not yet indicated how it would pay for the deferral.

UC Is Directed to Grow Enrollment Without Additional State Funding. The 2024‑25 Budget Act directed UC to increase resident undergraduate enrollment by 2,927 full‑time equivalent (FTE) students in 2024‑25. UC reports that it is exceeding that expectation—growing by an estimated 6,209 resident undergraduate FTE students. The 2024‑25 Budget Act also set a resident undergraduate enrollment expectation for UC in 2025‑26 and 2026‑27. The 2025‑26 budget plan maintains these expectations. Specifically, UC is to grow by an additional 2,947 FTE students in 2025‑26 and another 2,968 FTE student in 2026‑27. Yet, no associated state funding is provided to support the additional enrollment. (These amounts include 902 FTE resident students resulting from replacing nonresident students at three high‑demand campuses.)

Four Recommendations in Response to Budget Plan. (1) Given the state’s projected budget deficits, we recommend the Legislature set a more realistic budget expectation for UC by rejecting the deferrals and their associated out‑year payments. (2) We recommend revisiting the 2026‑27 resident undergraduate enrollment target and (3) pausing the nonresident enrollment replacement plan in 2026‑27. (4) Lastly, we recommend adopting language that maintains the resident enrollment growth achieved to date at the high‑demand campuses and avoids them beginning to replace resident students with nonresidents.

Introduction

Brief Focuses on UC. UC is one of California’s three public higher education segments. Under state law, UC provides undergraduate and graduate education, including doctoral programs and professional programs in law and medicine. It also serves as the primary state‑supported academic agency for research. The UC system consists of ten campuses. Nine of UC’s campuses enroll students across a range of disciplines, whereas one campus enrolls graduate health science students only. This brief analyzes the 2025‑26 budget plan for UC. The first section of the brief provides an overview of UC’s budget and the planned changes for 2025‑26. The second section focuses on UC’s core operations, whereas the third and final section focuses on enrollment.

Overview

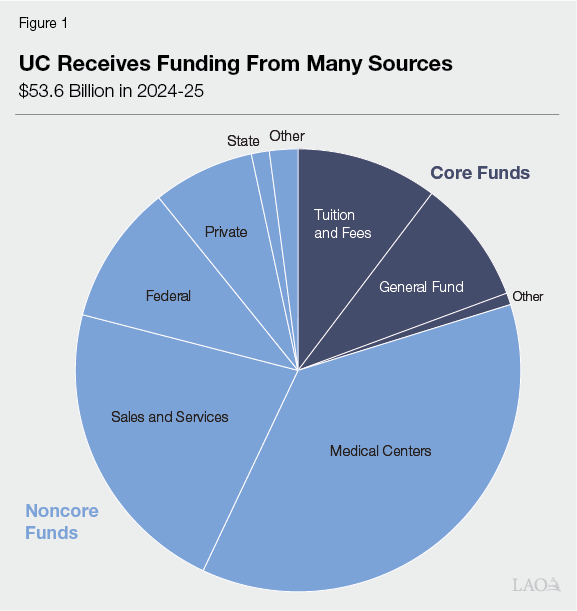

UC Budget Currently Is $53.6 Billion. Of the three public higher education segments, UC has the largest budget, with total funding greater than the California State University (CSU) and California Community Colleges (CCC) combined. As Figure 1 shows, UC receives funding from many different sources. The state generally focuses its budget decisions around UC’s “core funds”—the approximately 20 percent of UC’s budget that supports undergraduate and graduate education and certain state‑supported research and outreach programs. Core funds at UC primarily consist of student tuition and fee revenue and state General Fund. A small portion comes from lottery funds, a share of patent royalty income, and overhead funds associated with federal and state research grants. Between 2023‑24 and 2024‑25, ongoing core funds increased 3.4 percent. Ongoing core funds per student increased by 1.3 percent. UC’s noncore funds include revenue from its medical centers, sales and services, federal research grants, and philanthropic support.

Ongoing Core Funding Decreases by $30 Million (0.3 Percent) in 2025‑26. As Figure 2 shows, revenue generated from tuition and fees is expected to increase by $241 million (4.4 percent) in 2025‑26. State General Fund decreases by $272 million (5.6 percent), while other core funding is expected to remain flat. The increase in tuition and fee revenue is a result of higher tuition charges as well as anticipated enrollment growth. Given a small expected increase in enrollment, ongoing core funding per student decreases 0.5 percent.

Figure 2

At UC, State Funding Reduction Is Mostly Offset by More Tuition Revenue

Ongoing Core Funding (Dollars in Millions)

|

2023‑24 |

2024‑25 |

2025‑26 |

Change from 2024‑25 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Ongoing Core Funds |

|||||

|

Tuition and feesa |

$5,268 |

$5,498 |

$5,740 |

$241 |

4.4% |

|

General Fundb |

4,717 |

4,858 |

4,587 |

‑272 |

‑5.6 |

|

Lottery |

65 |

59 |

59 |

— |

— |

|

Other core fundsc |

409 |

401 |

401 |

— |

— |

|

Totals |

$10,459 |

$10,817 |

$10,787 |

‑$30 |

‑0.3% |

|

FTE studentsd |

293,483 |

299,486 |

300,111 |

625 |

0.2% |

|

Ongoing core funding per student |

$35,638 |

$36,119 |

$35,942 |

‑$177 |

‑0.5% |

|

aIncludes funds that UC uses for tuition discounts and waivers. bReflects reductions pursuant to Control Section 4.05 of the 2024‑25 Budget Act. Specifically, the 2024‑25 amounts reflects a $125 million General Fund reduction, and the 2025‑26 amount reflects a $397 million General Fund reduction. cIncludes a portion of overhead funding on federal and state grants and a portion of patent royalty income. dFTE is 30 credits for an undergraduate and 24 credits for a graduate student. Student counts include residents and nonresident students. |

|||||

|

FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

Budget Plan Reflects Ongoing Reduction in State Support in 2025‑26. The budget plan includes a $272 million ongoing General Fund reduction for UC. The reduction equates to a 5.6 percent decrease in UC’s state General Fund support compared to 2024‑25. (Though the administration cites a reduction of $397 million, this is offset by a restoration of $125 million, resulting a net reduction of $272 million.) This reduction is pursuant to Control Section 4.05 of the 2024‑25 Budget Act, which applied reductions of up to 7.95 percent to state operations across state government. The administration is giving UC flexibility in determining how it implements the reduction. (In the nearby box, we discuss the impact of Control Section 4.05 on UC in comparison to other state agencies.) The budget plan also provides $1.3 million in one‑time General Fund support for the Nutrition Policy Institute. This funding represents the final installment of a four‑year funding agreement (totaling $7.4 million) for the institute.

Control Section 4.05 Impacts UC Differently Than Other State Agencies

UC Differs From Other State Agencies in Significant Ways. Though the University of California (UC) was included in the Control Section 4.05 reductions, it differs from other state agencies in notable ways. One difference is that the state designates all UC appropriations as “state operations,” with none designated as “local assistance.” This means that all university spending at both the system and campus levels are designated as state operations. In contrast, the state is not applying Control Section 4.05 reductions to other agencies’ local assistance programs. Applying a flat percentage reduction to state operations funding for UC therefore results in a much more sizeable cut—one that is likely to have a direct impact on campuses. Another difference is that UC generates substantial nonstate revenue through student tuition. After accounting for anticipated growth in tuition revenue, UC’s total core funding is basically flat, even with the cuts to their state funding. A third notable difference is that the state does not directly authorize each employee position at UC, as is typically the case with other state agencies. Instead, the UC Board of Regents have that authority. This is why UC was excluded from the vacant positions sweep imposed on other state agencies by Control Section 4.12 of the 2024‑25 Budget Act.

Plan Includes Funding “Deferrals” for UC. In May 2022, the administration announced a compact with UC to provide 5 percent annual base General Fund increases from 2022‑23 through 2026‑27. As noted earlier, the state budget plan, however, includes no base increase for UC in 2025‑26. As Figure 3 shows, the plan defers the base increase ($241 million) the Governor intended to provide in 2025‑26 until 2027‑28. It also defers year‑four funding ($31 million) for replacing nonresident with resident students at three high‑demand UC campuses (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego). Despite the deferrals, the administration expects UC to continuing growing resident enrollment and reducing nonresident students in 2025‑26, along with meeting various other compact expectations. Under the deferral plan, UC would receive the anticipated year five base increase and nonresident replacement funding in 2026‑27, along with one‑time back payments for 2025‑26 costs. Then, in 2027‑28, it would receive the deferred year four base increase and nonresident replacement funding, along with one‑time back payments for 2026‑27 costs. The plan results in an initial reduction in General fund support, followed by a large General Fund increase in 2026‑27 and a more moderate increase in 2027‑28.

Figure 3

State Funding for UC Is Volatile Under Budget Plan

Reflects Multiyear Assumptions Under Budget Plan, General Fund (Dollars in Millions)

|

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

2027‑28 |

|

|

Ongoing Changes |

|||

|

Base reduction |

‑$397 |

— |

— |

|

Deferral of year 4 base increaseb |

— |

— |

$241 |

|

Deferral of year 4 nonresident replacement fundingb |

— |

— |

31 |

|

Anticipated year 5 base increase |

— |

$254 |

— |

|

Anticipated year 5 nonresident replacement funding |

— |

30 |

— |

|

One‑Time Back Payments |

|||

|

Base costs |

— |

$241 |

$241 |

|

Nonresident relacement costs |

— |

31 |

31 |

|

One‑Time Adjustmentsc |

$125 |

— |

‑$272 |

|

Totals |

$4,587 |

$5,142 |

$5,413 |

|

Change from prior year |

‑5.6% |

12.1% |

5.3% |

|

aIn 2025‑26, the Governor will be entering year 4 of his compact with the UC President. The fifth and final year of this compact is 2026‑27. A new governor will take office in 2027‑28. bThe Governor proposes to defer the year 4 base increase and nonresident replacement funding from 2025‑26 to 2027‑28. cIn 2025‑26, reflects the restoration of $125 million one‑time base reduction applied in 2024‑25. In 2027‑28, reflects removal of prior‑year, one‑time back payments. |

|||

Core Operations

In this part of the brief, we provide background on UC’s core operations, describe the state’s multiyear budget plan, assess that plan, and make an associated recommendation. (We address nonresident enrollment issues in the “Enrollment” section of this brief, but we address the associated funding deferral in this section.)

Background

In this section, we cover UC’s core funds and core operating costs.

Funding

UC Covers Its Core Operating Cost Increases From Two Main Sources. UC’s largest core fund source is student tuition and fee revenue. UC also relies heavily on state support for its core undergraduate and graduate programs. In 2024‑25, just over half of UC’s core funding came from student tuition and fee revenue, whereas 45 percent came from state General Fund.

State Support Has Been Growing Somewhat More Quickly Than Tuition Revenue. Ten years ago, UC relied somewhat more heavily on student tuition and fee revenue (54 percent) and less heavily on state support (41 percent). The primary reason for the decline in the tuition share is that UC generally held its tuition charges flat from 2011‑12 through 2021‑22. During this period, UC increased its systemwide tuition charges only once. In 2017‑18, UC raised it resident undergraduate and graduate academic charges by 2.7 percent. In a few other years, UC also assessed small increases to its Student Services Fee. In contrast to tuition charges, state support generally was rising over this period. Since 2013‑14, the state has provided UC with General Fund base increases every year but one. (In 2020‑21, the state reduced General Fund support for UC, but it restored funding the following year.)

UC Continues Implementing Its Tuition Stability Plan. In 2021, the Board of Regents approved a new tuition policy. Under this policy, tuition is raised annually for new undergraduates and all graduate students, while tuition remains flat for continuing undergraduates (for up to six academic years). Tuition increases generally are based on a three‑year rolling average of the annual change in the California Consumer Price Index, with an annual cap of 5 percent (unless modified by the Board of Regents). As a result of the new tuition policy, tuition and fee revenue has been growing more quickly at UC over the past few years. The first year of tuition increases under this policy was 2022‑23. In 2024‑25, UC estimates it is generating $191 million in additional net tuition revenue (from its tuition and enrollment increases combined, after accounting for financial aid earmarks). Whereas previous tuition increases generally were precipitated by reductions in state General Fund support, UC’s new policy was largely driven by a desire to expand its overall budget capacity.

UC Relies on a Few Alternative Ways to Support Core Operations. For many years, UC has identified certain ways to improve its core budget capacity beyond reliance on tuition revenue and state support. One way has been to place its pooled cash in investment accounts and use some of the annual investment earnings to support core operations. In UC’s 2024‑25 budget plan, it identified $90 million in investment earnings that it designated for its core operations. UC also regularly seeks to contain growth in its operating costs. One way it regularly realizes operational savings is through negotiating discounts and rebates from vendors and service providers. In 2024‑25, UC identified $11 million in annual savings attributable to these efforts.

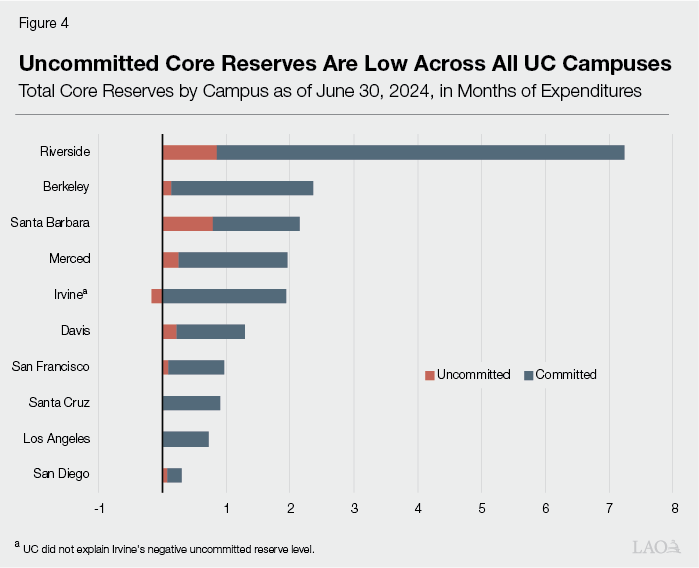

UC Has Relatively Low Levels of Core Reserves. Like many other universities (as well as public and private entities more generally), UC maintains reserves. It leaves some reserves uncommitted, such that they are available to address economic uncertainties, including state budget reductions. The rest of its reserves are committed to planned activities, such as faculty recruitment and retention, certain capital outlay costs, and other strategic program investments (including developing new academic programs, expanding existing programs, and upgrading campus‑wide information technology systems). Some, but not all, of these commitments could be revisited in the face of a fiscal downturn. Unlike CSU, UC does not have a systemwide reserves policy that sets a reserve target. As of June 2024, UC reported $1.5 billion in total core reserves, of which $155 million was uncommitted. UC’s uncommitted reserves reflect just under six days (1.6 percent) of its total annual core operating expenditures. UC’s reserves are lower than general fiscal best practices. The Government Finance Officers Association historically has recommended that government agencies hold at least two months of unrestricted budgetary fund balances (though exceptions are considered depending on certain factors such as the size of the agency, its diversification of revenue streams, the volatility of those revenue streams, and overall risk exposure).

Reserves Total Less Than One Month of Expenditures at All Campuses. In the absence of a systemwide reserves policy, UC allows its ten campuses to determine their own reserve levels. Campus policies vary but typically aim for uncommitted core reserves worth one to three months of core expenditures. Figure 4 shows core reserves at each UC campus as of June 30, 2024. Total core reserves (committed and uncommitted combined) ranged from less than one month of expenditures at the San Diego campus to over seven months of expenditures at the Riverside campus. Uncommitted reserves for economic uncertainties, however, equated to less than one month of expenditures at all campuses.

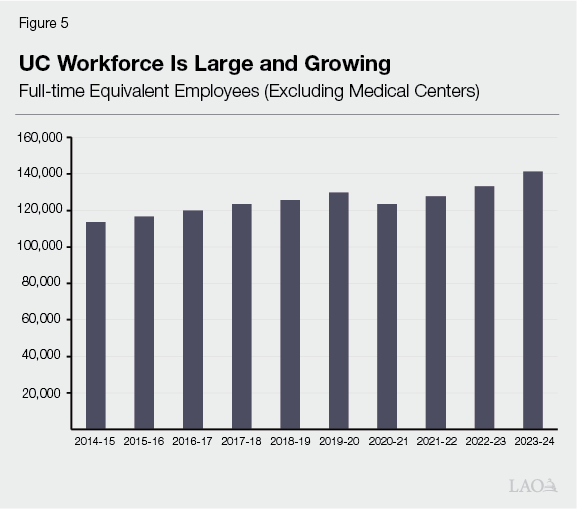

Cost Pressures

UC’s Workforce Is Large and Has Grown Notably Over Time. In April 2024, UC employed nearly 143,000 FTE campus employees (excluding medical centers). As Figure 5 shows, the number of FTE employees at UC has generally been trending upward over time. The only staffing decline from 2014‑15 through 2023‑24 was a 5 percent decline in 2020‑21, as UC responded to the pandemic and associated fiscal reductions. Over the past decade, staffing generally has been outpacing enrollment growth. Over the last ten years, UC’s FTE workforce has grown by 24 percent, exceeding FTE student growth of 17 percent. In 2023‑24, UC had 1 FTE employee for every 2.1 FTE students.

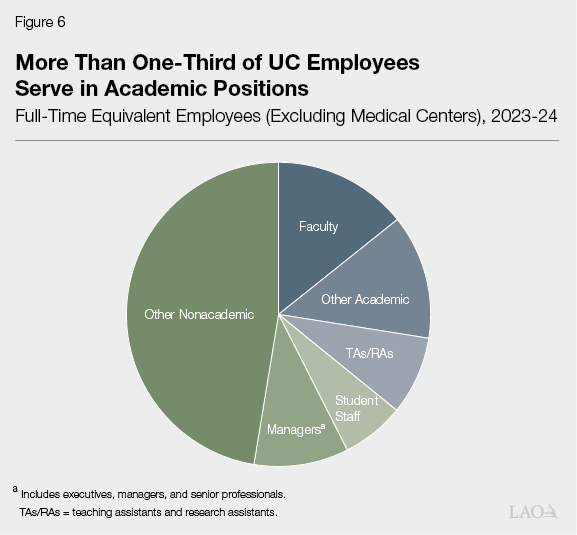

UC Workforce Consists of a Mix of Academic and Nonacademic Positions. As Figure 6 shows, more than one‑third of UC campus employees in 2023‑24 served in academic positions, with the remainder serving in various nonacademic positions. Nonacademic positions include managers, program directors, and support staff serving in many areas, including maintenance, food services, student advising and counseling, human resources, budget, accounting, and information technology, among others. While the composition of the workforce has not changed much from 2014‑15 through 2023‑24, the most pronounced change has been in the share of managers, which has grown from 7 percent to 10 percent of the total workforce.

UC’s Largest Operating Cost Is Employee Compensation. Like many other state agencies, the largest component of UC’s budget is employee salaries and benefits (comprising 74 percent of its core expenditures in 2023‑24). UC has more control than most state agencies, however, over its compensation costs, partly because most of its employees (nearly 80 percent) are not represented by a labor union. The Board of Regents directly sets salaries and benefits for these employees. UC generally offers these employees annual salary increases, though it tends not to provide such increases during fiscal downturns. UC collectively bargains salaries and benefits for its represented employee groups, negotiating with eight systemwide labor unions. As with CSU, the Legislature does not ratify UC’s collective bargaining agreements.

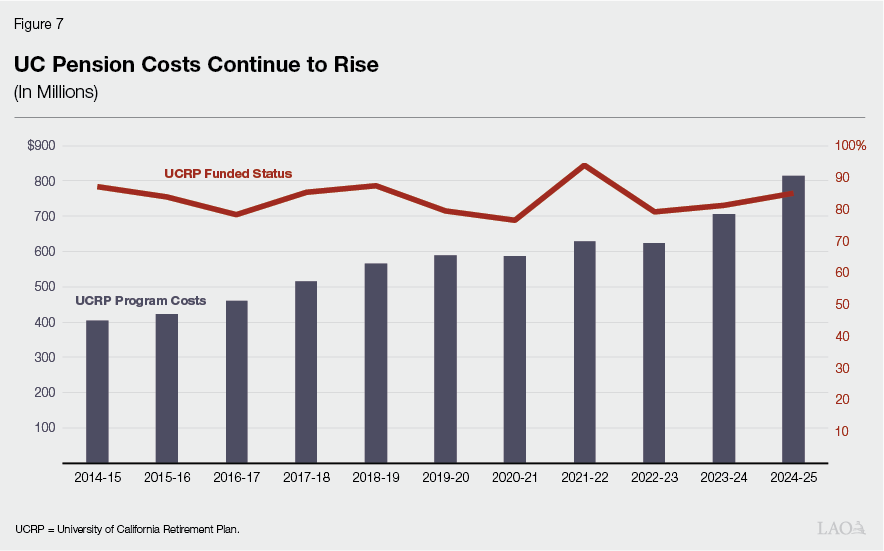

UC Manages Its Own Retirement System, Costs Have Been Rising. Whereas many state employees participate in the California Public Employees’ Retirement System or the California State Teachers’ Retirement System, UC employees participate in the University of California Retirement Plan (UCRP). The UC Board of Regents manages UCRP. Each year, the Board of Regents determines how much UC contributes to the pension program. For the last ten years, the UC employer contribution rate has increased gradually, from 14.6 percent of payroll in 2015‑16 to 17.72 percent in 2024‑25. As Figure 7 shows, annual program costs have steadily grown over this period, reaching more than $800 million in 2024‑25. In 2024‑25, UCRP’s funded status (comparing assets to liabilities) was 85 percent. UCRP’s funded status has tended to be better than other California state retirement plans

Health Care Costs Have Been Growing. UC offers a range of health plans for UC employees and retirees, with premiums set annually for the respective plans. The premium costs that UC covers for employees depends on an employee’s income level, with lower‑paid employees receiving a higher share of their premium costs covered. UC’s health care spending generally has increased over time, growing from $532 million in 2015‑16 to an estimated $760 million in 2024‑25. While health care costs at UC are growing, these costs as a share of UC’s total core expenditures have remained fairly stable over the past decade, hovering around 7 percent.

Way UC Finances Its Facilities Differs From Other State Agencies. Prior to 2013‑14, the state financed UC academic facilities the same way it financed most other state facilities—using state general obligation bonds and state lease revenue bonds. Chapter 50 of 2013 (AB 94, Committee on Budget) established a new system for UC. Under this system, UC is authorized to sell its own university bonds and use a portion of its annual state appropriation to cover associated debt service. Since this new system has been in place, the state has given UC authority to finance $4 billion in facility projects using university bonds. UC is using unrestricted funds from within its main state appropriation to cover the debt service costs associated with $2.4 billion of these projects. The state has earmarked General Fund to cover the remaining debt service costs (as described below).

Debt Service Obligations Have Been Increasing. The state changed the way it financed UC facilities primarily because it wanted to provide UC with a greater incentive to contain costs by having to prioritize its operating and capital spending from within its annual state appropriation. The state, however, recently veered from this approach. Over the past few years, the state approved $1.6 billion in new UC projects, including certain student housing projects as well as new medical education buildings and other expansion projects at the Merced and Riverside campuses. Though UC still was directed to sell university bonds for these projects, the state earmarked General Fund support to cover the associated debt. This approach increased annual state debt service costs for UC facilities by $105 million. In 2024‑25, UC estimates its total debt service costs are further increasing by $8 million (2 percent), altogether reaching $469 million.

UC Has Large Seismic Safety and Capital Renewal Backlogs. Of the state‑supported academic facility projects UC has undertaken since 2013‑14, nearly $1.2 billion has been for seismic safety and capital renewal projects (including major renovations, building replacements, and infrastructure improvements). Despite these additional facility projects, UC continues to report large and growing project backlogs. As of November 2024, UC identified backlogs of $12 billion in state‑supported seismic safety projects and $9.1 billion in state‑supported capital renewal projects.

Student Financial Aid and Other Cost Pressures Also Exist. Beyond employee compensation and facility costs, UC faces various other annual cost pressures. The largest remaining cost involves its institutional student financial aid programs. UC designates a portion of new student tuition revenue generated by tuition and enrollment increases to its institutional aid programs. In 2024‑25, UC reports spending an estimated $1.2 billion on its largest institutional aid program, which provides gift aid for undergraduates with financial need. Though much smaller in magnitude, UC also can experience cost increases relating to operating expenses and equipment (OE&E). OE&E costs tend to grow with inflation over time, though UC tries to contain these costs through operational efficiencies.

2025‑26 Budget

In this section, we discuss UC’s sources of funding as well as its spending priorities for 2025‑26.

2025‑26 Funding

Budget Plan Reflects Ongoing Reduction in State Support for UC in 2025‑26. Consistent with the budget plan set forth in June 2024, ongoing General Fund support for UC is reduced by $272 million (5.6 percent) in 2025‑26. (Compared to June 2024 estimates, the UC amount is $20 million larger due to the administration calculating the reduction off a higher 2024‑25 base.) This reduction is pursuant to Control Section 4.05 of the 2024‑25 Budget Act. The administration is providing UC flexibility in deciding how to accommodate the reduction.

Budget Plan Defers General Fund Base Increase. Also consistent with the June 2024 budget plan, an ongoing General Fund augmentation of $241 million (about 5 percent) for UC is deferred from 2025‑26 until 2027‑28. Under the deferral arrangement, one‑time back payments would be provided to UC in 2026‑27 (for 2025‑26 costs) and 2027‑28 (for 2026‑27 costs).

Budget Plan Also Defers Nonresident Enrollment Replacement Funding. For the past three years, the state has been providing UC with funding to replace nonresident students at three high‑demand campuses (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego) with resident undergraduate students. Consistent with the June 2024 budget plan, the fourth year of this funding ($31 million) is deferred two years (from 2025‑26 to 2027‑28). Similar to the deferred base augmentation, one‑time back payments would be provided to UC in 2026‑27 (for 2025‑26 costs) and 2027‑28 (for 2026‑27 costs). Despite the lack of funding, the administration continues to expect UC to replace nonresident students at the three high‑demand campuses in 2025‑26.

UC Anticipates Additional Revenue From Tuition and Fees. In 2025‑26, systemwide tuition and fees is set at $14,934 for new resident undergraduate students, reflecting an increase of $498 (3.4 percent) from 2024‑25. UC also is raising nonresident supplemental tuition in 2025‑26. The supplemental rate for nonresident undergraduates (which is in addition to the base rate for resident students) is set at $37,602. The supplemental rate rises by $3,402 (10 percent) from 2024‑25. The planned increase for nonresident students is higher than the inflation‑based rate generally aimed for under UC’s tuition policy. UC indicates this will likely be a one‑time action and was done so that nonresident tuition rates are more in‑line with select peer institutions, such as the University of Michigan and the University of Virginia. UC estimates it will generate $225 million in additional revenue from its tuition increases in 2025‑26. It plans to use $84 million of this additional revenue for institutional financial aid. (In addition, the California Student Aid Commission budget includes $44 million in higher associated Cal Grant costs for UC students due to its tuition increases. Many UC students with financial need receive full tuition coverage under the Cal Grant program.)

UC Anticipates Additional Revenue From Other Sources in 2025‑26. In addition to General Fund support and tuition and fee revenue, UC plans to use $20 million from its investment earnings for its core operating costs in 2025‑26. UC also anticipates generating $9 million in freed‑up funds from procurement savings and other operational efficiencies that it can use for its core operations in 2025‑26.

UC Spending Priorities

UC Has Identified Its Spending Priorities for 2025‑26. As Figure 8 shows, UC has identified a total of $513 million in new spending priorities for 2025‑26. UC treats some of these spending priorities as nondiscretionary (meaning they must be covered). For example, UC is legally required to cover the costs of compensation packages for represented personnel with contracts already in place, certain faculty merit salary adjustments, and certain contractual costs associated with retirement and employee health benefits. Various other costs are discretionary. These costs include salary enhancements for nonrepresented personnel and certain OE&E costs (such as office supply purchases, travel, and subscription services).

Figure 8

UC Has Identified Several

Spending Priorities

Estimated Spending Increases, 2025‑26 (In Millions)

|

Spending Priorities |

|

|

Nondiscretionary |

|

|

Represented employee salaries |

$51 |

|

Health benefits for active employees |

40 |

|

Faculty merit salary adjustments |

36 |

|

Retirement contributions |

19 |

|

Health benefits for retirees |

11 |

|

Subtotal |

($158) |

|

Discretionary |

|

|

Student financial aid |

$102 |

|

Faculty general salaries |

80 |

|

Non‑represented staff salaries |

70 |

|

Enrollment growth |

63 |

|

Operating expenses and equipment |

36 |

|

Other |

4 |

|

Subtotal |

($354) |

|

Total |

$513 |

Benefit Costs Estimated to Grow by a Total $71 Million in 2025‑26. UC expects its costs to increase for health care and pension benefits. UC estimates that health benefit costs for active employees will grow by $40 million. This growth is based on an anticipated increase in health care costs of 7.1 percent in 2025‑26. UC also projects retiree health benefit costs will grow by $11 million due to the combined effect of higher premiums and a projected increase in the number of retirees. UC will continue assessing a payroll charge of 2.23 percent in 2025‑26 to cover these costs. While the UC employer contribution rate for UCRP is set to decrease to 17.42 percent of payroll in 2025‑26 (down from 17.72 percent in 2024‑25), retirement costs are expected to grow by $19 million due to overall growth in payroll costs.

Some Collective Bargaining Agreements Already Are in Place for 2025‑26. UC has contracts in place that extend through 2025‑26 for six of its eight unions. The terms of these contracts vary, but they generally provide 3.5 percent to 5 percent salary increases. UC has open contracts with the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees and the University Professional and Technical Employees, which reflect approximately 3 percent of UC’s workforce. UC has a total of $51 million in its budget plan for cost increases associated with its collective bargaining agreements.

Funds Permitting, UC Has Plan to Raise Employee Salaries for Nonrepresented Employees. The 2025‑26 budget plan approved by the Board of Regents includes a total of $150 million for potential salary increases for nonrepresented faculty and staff. UC indicates that this reflects an estimated 3.7 percent in UC’s associated salary pool (intended to be comparable to the increases provided for represented employees). UC indicates it will wait to make final decisions regarding most salary increases for nonrepresented faculty and staff until its fiscal picture for 2025‑26 is clearer.

UC Also Anticipates Other Cost Increases in 2025‑26. In addition to anticipated growth in compensation costs, UC has plans to increase its institutional student financial aid spending by $102 million in 2025‑26. UC uses a portion of its tuition revenue to pay for these costs. UC also estimates that costs associated with continued enrollment growth would be $63 million. Additionally, UC projects that 2025‑26 OE&E costs will grow by $36 million. The 2024‑25 OE&E costs are projected to increase by the year‑over‑year percentage growth in the California Consumer Price Index.

Assessment

In this section, we assess the impact of the multiyear budget plan on UC and the state.

Impact on UC

UC Has a Projected Budget Gap in 2025‑26. Though UC has identified $513 million in core spending increases (with about 70 percent of that spending identified as discretionary), its core funding is projected to decrease by $30 million, leaving a budget gap. To accommodate any of UC’s identified cost increases, it will need to make budget adjustments.

UC Began Making Budget Adjustments in Current Year. In 2024‑25, UC’s ongoing core funding increased $358 million (3.4 percent). This increase consisted of $230 million additional tuition revenue and $142 million additional state General Fund support. Despite this increase, UC indicates it did not receive enough support to cover all of its budget priorities. Moreover, UC was aware of the state budget plan to reduce its funding by $272 million in 2025‑26. In response, the University of California Office of the President (UCOP) established a systemwide budget management workgroup to identify common campus budget challenges, along with potential actions campuses could implement to align their funding and spending. Specific budget decisions, however, were ultimately left up to each campus (with a majority of the budgetary decisions made at the unit/department level).

Campuses Are Already Taking a Range of Actions. Campus actions have generally fallen into three broad categories:

- Cost Reduction. These measures include hiring freezes, holding vacant positions open, reducing nonessential expenditures (such as travel), and deferring capital projects.

- Operational Efficiencies. These measures include restructuring and consolidating services.

- Revenue Generation. These measures include expanding self‑supporting programs and growing nonresident enrollment at certain campuses currently below the 18 percent cap.

UC Plans Further Action to Address 2025‑26 Reduction. UCOP plans to allocate the proposed $272 million General Fund base reduction across its campuses. Campuses, in turn, will continue to have discretion in making any needed budget adjustments. UCOP notes that many campuses intend on keeping the reductions adopted in 2024‑25 in place for 2025‑26, but campus planning remains ongoing and subject to change depending on the state’s budget condition. UC has no explicit plans regarding how it would respond to a deferred augmentation, with state payment being delayed one or more years. Were UC to raise its spending in 2025‑26 on the assumption it would receive a deferred state payment in 2026‑27, and then state payment were not forthcoming, UC would face more disruptive spending choices at that time.

State Impact

Budget Plan Calls to Increase UC Funding Significantly in 2026‑27 Despite Projected Deficit. As we discuss in The 2025‑26 Budget: Overview of the Governor’s Budget, the state faces significant General Fund operating deficits in the coming years. Under the budget plan for UC, the state is committing to increase General Fund spending for UC by $556 million in 2026‑27. Rather than increasing university costs, the state historically has contained costs when facing multiyear budget deficits. Moreover, the state has set forth no plan as to how it would pay for such a large UC augmentation while facing a deficit. Given the state budget plan does not include a base increase for UC in 2025‑26, it is unlikely the state could afford such an increase in 2026‑27 (absent a change in the state’s fiscal condition or new budget solutions).

Recommendation

Recommend Removing Deferrals to Signal More Realistic Budget Expectations. Last year, the state provided a clear signal to UC that it was to begin planning for a base General Fund reduction in 2025‑26. This approach gave UC time to plan and make the associated adjustments within its budget. Given the state’s projected deficit in 2026‑27, the state likely will not have budget capacity to support substantial increases in General Fund spending for any programs, including UC. Rather than continuing with the deferral plans and committing to out‑year funding increases, we recommending sending a more realistic signal to UC that it may not receive an increase in its state General Fund support in 2026‑27. Signaling this expectation is more helpful to UC than setting an explicit expectation it will receive substantial additional state support in 2026‑27, without any specific plan to ensure that funding is forthcoming. It also avoids having the state create new fiscal obligations it cannot currently afford. If the state’s fiscal condition improves over the next year, the Legislature could consider providing additional General Fund support for UC at that time.

Enrollment

In this section, we first provide background on the state’s approach to funding enrollment growth at UC and cover enrollment trends. We then discuss the state’s enrollment plans for UC in 2025‑26 and 2026‑27. Next, we assess those plans and make associated recommendations.

Background

UC Enrolls a Mix of California Resident and Nonresident Students. In 2023‑24, of the nearly 293,500 FTE students UC enrolled, 82 percent were California residents and 18 percent were nonresidents. Compared to the two other segments, UC enrolls a notably larger share of nonresident students. (In 2023‑24, nonresidents comprised 5.5 percent of CSU FTE students and an estimated 3 percent of CCC FTE students.) Within UC, nonresident students are more common in graduate programs. In 2023‑24, one‑third of UC graduate students are classified as nonresidents, compared to 15 percent of UC undergraduates.

UC Enrolls a Mix of Freshmen and Transfer Students. Besides aiming to enroll a mix of resident and nonresident students, UC tries to have each new incoming undergraduate class have a certain share of freshmen and transfer students. Specifically, UC aims to enroll one resident transfer student for every two resident freshmen. In fall 2024, UC estimates that it will nearly achieve this goal.

State Typically Sets Resident Enrollment Targets and Provides Associated Funding. Over the past two decades, the state’s typical enrollment approach for UC has been to set systemwide resident enrollment targets. These targets typically have applied to total resident enrollment, giving UC flexibility to determine the mix of undergraduate and graduate students. If the total systemwide target has included growth (sometimes the state leaves the target flat), the state typically has provided associated General Fund augmentations. Augmentations have been calculated using an agreed‑upon per‑student funding rate derived from the “marginal cost” formula. This formula estimates the cost to enroll each additional student and shares the cost between the state General Fund and student tuition revenue. In 2024‑25, the total marginal cost per student is $21,455, with a state share of $11,930.

Recently, State Has Made Two Modifications to Its Enrollment Growth Approach. One modification is that the state has been setting enrollment growth targets only for undergraduates. Another modification is that the state generally has been trying to better align its targets with UC’s admissions cycle by setting enrollment targets for budget year plus one. UC completes its admissions cycle for the coming fall term before the state enacts the annual budget each June. Setting an enrollment growth target for budget year plus one allows the state to influence UC’s planning for the next admissions cycle prior to UC making its admission decisions.

State Continues Nonresident Enrollment Reduction Plan. Another important change in recent years is that the state has acted to limit the number of nonresident undergraduates at UC, with the intent to make more slots available for resident undergraduates at high‑demand campuses. Specifically, the state has directed UC to reduce nonresident undergraduate enrollment at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses by a total of 902 FTE students annually and increase resident undergraduate enrollment by the same amount. To help the campuses achieve this goal, the state has provided UC with ongoing General Fund support primarily to backfill the lost nonresident supplemental tuition revenue. The nonresident enrollment reduction plan began in 2022‑23 and was intended to extend through 2026‑27. By 2026‑27, UC campuses are to have nonresident students comprise no more than 18 percent of their total undergraduate enrollment. (The 18 percent cap applies to all UC campuses, but only the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses currently are above that cap.)

Last Year’s Budget Act Included Enrollment Growth Expectations for the Next Few Years. Specifically, the 2024‑25 Budget Act set an expectation that UC grow by 2,927 resident undergraduate FTE students in 2024‑25, another 2,947 FTE students in 2025‑26, and another 2,968 FTE students in 2026‑27. These amounts reflect annual growth of 1.4 percent. (These amounts include the additional 902 resident undergraduate FTE students resulting from the nonresident replacement plan.) The state’s intent was that UC would fund this new growth from base General Fund augmentations provided in each of those years. Under this growth plan, UC resident undergraduate enrollment would reach 212,503 in 2026‑27.

UC Has Graduate Growth Plans. Unlike for UC undergraduates, the state has not been setting enrollment targets for UC graduate students. The Governor and UC, however, have compact goals relating to graduate enrollment. Specifically, UC set a plan to increase enrollment in its state‑supported graduate programs by a total of 2,500 students (resident and nonresident students combined) over four years. UC originally intended to add this enrollment in even increments (625 FTE students per year) beginning in 2023‑24 and extending through 2026‑27. Though not earmarked in the state budget act, graduate enrollment growth is supported by state funding and tuition revenue, among other sources.

Trends

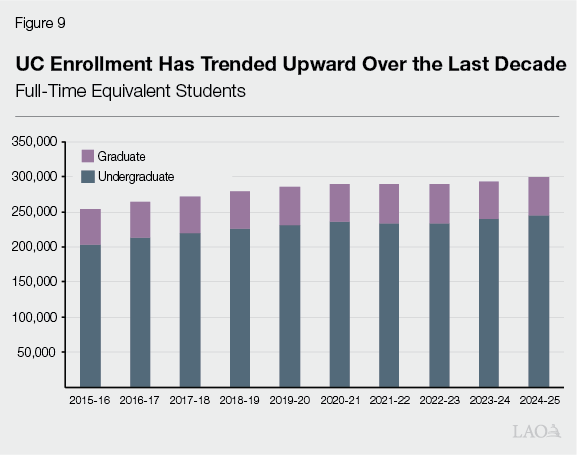

UC Enrollment Has Grown Over the Past Decade. As Figure 9 shows, UC enrollment has increased every year but one (2022‑23) over the past decade. Total enrollment has grown by approximately 46,000 students (18 percent). As enrollment has increased, the share of undergraduates has grown slightly (from 80 percent to 82 percent of overall enrollment), as the share of graduate students has declined slightly (from 20 percent to 18 percent). Undergraduate enrollment growth has varied somewhat across UC campuses. Over the past decade, UC Santa Cruz has experienced the least amount of growth. UC San Diego has added the greatest number of undergraduates, and UC Merced has grown at the fastest rate.

UC Expects to Exceed Its Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Target in 2024‑25. Based on data from the summer and fall 2024 terms, UC estimates that its resident undergraduate enrollment is 3,270 FTE students above the 2024‑25 Budget Act target. This growth is more than double the state’s enrollment expectation that year. Rather than reaching a resident undergraduate enrollment level of 206,588 FTE students, UC anticipates growing to 209,858 FTE students. This level of growth even exceeds the 2024‑25 Budget Act enrollment target set for UC in 2025‑26 (by a few hundred students). UC is planning to apply the excess growth in 2024‑25 toward its 2025‑26 enrollment target.

Growth in New Transfer Students More Than Offsets Decline in New Freshmen. Figure 10 shows UC’s cohort of new incoming students (headcount) grew slightly in fall 2024 over fall 2023. Reversing a three‑year trend, new transfer enrollment increased for the first time since fall 2020. The number of new resident freshmen declined year over year, breaking a pattern of annual growth for this group that began in fall 2020.

Figure 10

Growth of New Transfer Students More Than

Offsets Decline in New Freshmen

New Undergraduate Headcount, Fall Term

|

Fall 2023 |

Fall 2024 |

Change From Fall 2023 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

|||

|

Freshmen |

||||

|

Resident |

42,108 |

41,950 |

‑158 |

‑0.4% |

|

Nonresident domestic |

4,616 |

4,262 |

‑354 |

‑7.7 |

|

Nonresident International |

4,245 |

4,409 |

164 |

3.9 |

|

Subtotals |

(50,969) |

(50,621) |

(‑348) |

(‑0.7%) |

|

Transfer/Othera |

||||

|

Resident |

17,899 |

18,694 |

795 |

4.4% |

|

Nonresident domestic |

396 |

366 |

‑30 |

‑7.6 |

|

Nonresident international |

1,489 |

1,621 |

132 |

8.9 |

|

Subtotals |

(19,784) |

(20,681) |

(897) |

(4.5%) |

|

Totals |

70,753 |

71,302 |

549 |

0.8% |

|

aIncludes CCC and other transfer students. |

||||

UC Expects to Meet Its Nonresident Enrollment Reduction Goals in 2024‑25. Compared to 2023‑24, nonresident undergraduate enrollment declined at the Berkeley campus by 782 FTE students and at the Los Angeles campus by 294 FTE students. Together, these two campuses exceeded the combined state reduction target of 902 FTE students. UC San Diego increased its nonresident undergraduate enrollment by 83 FTE students, but it grew its resident undergraduate enrollment at an even greater pace. All three campuses reduced nonresident undergraduate enrollment as a share of their total undergraduate enrollment. The Berkeley campus made the most progress (reducing its nonresident share by 2.2 percentage points), whereas the San Diego campus made the least progress (reducing its nonresident share by 0.4 percentage points). All three campuses have a nonresident share that is below 20 percent in 2024‑25.

UC Does Not Plan to Meet Graduate Growth Target. Unlike for undergraduate enrollment, graduate enrollment growth targets were not included in the 2024‑25 Budget Act. Nonetheless, UC has been tracking its graduate enrollment relative to its compact goals. UC does not expect to meet the overall 2,500 graduate enrollment growth target identified in the compact. UC notes that the baseline from which that target was set reflected an unusual high point in 2021‑22. Though it did not realize at the time, UC has since learned that graduate enrollment in 2021‑22 was particularly high given a relatively large number of graduate students deferred enrollment in 2020‑21 due to issues relating to the pandemic. While UC believes graduate enrollment will not grow by 2,500 graduate students by 2026‑27, it indicated to us that campuses will continue to expand enrollment in graduate programs, with a particular emphasis on enrollment in programs that meet state workforce needs in the science, technology, engineering, mathematics and health sciences areas.

Enrollment Expectations for 2025‑26 and 2026‑27

Budget Plan Continues Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Expectations, but Does Not Provide Funding. The 2024‑25 Budget Act set a resident undergraduate enrollment expectation for UC in 2025‑26 and 2026‑27. The 2025‑26 budget plan maintains these expectations. Specifically, the budget plan sets forth that UC is to grow its resident undergraduate enrollment by 2,947 FTE students in 2025‑26, and another 2,968 FTE students in 2026‑27, for a total level of 212,503 FTE students that year. The budget plan does not contain any enrollment growth funding for UC in 2025‑26. However, it maintains provisional language permitting the Director of the Department of Finance (DOF) to reduce UC funding for each student below the expected 2025‑26 level. The provisional language indicates the reduction would be taken at the 2025‑26 state marginal cost rate of $11,640 per student.

Budget Plan Also Maintains Nonresident Enrollment Reduction Expectations, but Defers Funding. The budget plan also maintains the expectation that UC continue to reduce nonresident undergraduate enrollment by a total of 902 FTE students at the Berkeley, Los Angeles, and San Diego campuses in 2025‑26, replacing those students with residents. (The additional resident students are included in the targets mentioned above.) As with the base funding deferral, the budget plan defers $31 million ongoing General Fund that otherwise would have been provided in 2025‑26 to continue implementing the nonresident enrollment reduction plan to 2027‑28. The Governor proposes provisional budget language stipulating that if the actual reduction in nonresident undergraduate enrollment in 2025‑26 is fewer than 902 FTE students, then the Director of DOF is not obligated to provide the deferred payment.

Assessment

UC Has Concerns About Continuing to Meet Enrollment Targets Without State Funding. As noted in the “Trends” section, UC is exceeding its 2024‑25 resident undergraduate enrollment target. UC also reports it is on track to exceed its 2025‑26 resident undergraduate enrollment target, despite the lack of an increase in its state General Fund support under the 2025‑26 budget plan. For the 2025‑26 academic year, UC already has made many of its admissions decisions. UC has expressed concern about meeting the 2026‑27 resident undergraduate enrollment target in the absence of additional state funding. Similarly, UC has expressed concern about continuing to implement the nonresident undergraduate enrollment reduction plan in 2026‑27 without additional associated state funding. These concerns are warranted given the state’s projected out‑year budget deficits.

Enrollment Growth Above Target in 2025‑26 Likely to Impact Academic Programming. UC projects that its resident undergraduate enrollment will surpass the 2025‑26 state target by 1,225 FTE students. However, the state’s multiyear budget plan does not include funding for any enrollment growth and, instead, includes an ongoing General Fund reduction for UC in 2025‑26. To accommodate the student growth, while at the same time seeing a reduction in its state support, UC anticipates holding some positions open and slowing the hiring of faculty. The result of these actions is that class sizes will likely increase and fewer courses could be available for students in fall 2025.

Funding Enrollment Growth at Community Colleges Helps Maintain Overall College Access. As we discuss in The 2025‑26 Budget: Higher Education Overview, the Governor’s budget includes an increase in Proposition 98 General Fund to support enrollment growth at community colleges. If the state were to reduce ongoing General Fund for UC over one or more years and UC were to constrain its enrollment, community colleges could begin to attract students who otherwise might have enrolled directly at UC. That is, community colleges could help maintain overall college access in the state. Moreover, community colleges do so at a lower state cost relative to the state funding enrollment growth at the universities. (Another effect of this initial enrollment shift, however, is that UC could see pressure in the future resulting from a greater pool of transfer students.)

Recommendations

Revisit 2026‑27 Resident Undergraduate Enrollment Target. With UC having already made many of its 2025‑26 admissions decisions, modifying state 2025‑26 enrollment targets would have little effect at this point. The Legislature, however, still can influence UC’s 2026‑27 enrollment levels. Given the state’s projected deficit in 2026‑27, the state likely would not have budget capacity to support enrollment growth in 2026‑27. The Legislature could consider a couple of options. One option would be to hold UC’s enrollment flat at the estimated 2025‑26 level of 210,760 resident undergraduate FTE students. Under this option, UC would likely continue to implement cost saving measures, likely resulting in larger class sizes and potentially fewer course offerings. The effects would be less severe, however, than if the state maintained the higher enrollment targets under the budget plan (requiring UC to grow resident undergraduate enrollment to 212,503 FTE students in 2026‑27). Alternatively, the Legislature could lower UC’s resident undergraduate FTE enrollment level in 2026‑27 to some level it deemed appropriate given changes in UC’s total core funding. Lowering UC’s resident undergraduate enrollment target would alleviate some or all of the pressure UC would face to implement further cost savings measures.

Pause Nonresident Replacement Enrollment Reduction Plan. As previously mentioned, with many 2025‑26 admissions decisions already made, the Legislature has a greater ability to impact UC’s 2026‑27 enrollment decisions. In light of the state’s projected budget deficits, we recommend the Legislature pause the expectation that UC replace 902 nonresident undergraduate students with resident students in 2026‑27 at the three high‑demand campuses. The state could resume implementation of the nonresident reduction plan when its fiscal condition improves.

Adopt Language to Maintain Existing Ratio of Resident‑to‑Nonresident Students at High‑Demand Campuses in 2025‑26 and 2026‑27. We recommend the Legislature adopt provisional budget language directing UC to maintain the existing progress that campuses already have made regarding replacing nonresident with resident students at its high‑demand campuses. Specifically, the provisional language would stipulate that campuses exceeding the 18 percent nonresident undergraduate threshold shall not increase the percentage of nonresident undergraduate FTE students above their 2024‑25 levels. Adopting this language would ensure that these campuses do not undo some of the progress made over the past three years. That is, the language would deter the high‑demand campuses from effectively beginning to replace resident students with nonresident students.