Nick Schroeder

June 23, 2025

MOU Fiscal Analysis: Bargaining Unit 6 (Corrections)

The administration released a proposed labor agreement between the state and Bargaining Unit 6 (Corrections) on the evening of June 16, 2025. Unit 6 consists of correctional officers, parole agents, and other correctional staff who provide custody, supervision, and treatment of people in state custody. Unit 6’s current members are represented by the California Correctional Peace Officers Association (CCPOA). The current memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the state and CCPOA is scheduled to expire on July 2, 2025. Our analysis of the current MOU and other labor agreements proposed in the past are available on our State Workforce webpages. If ratified by the Legislature and CCPOA members, the proposed agreement would be the successor MOU to the current MOU. In the event that the proposed agreement is not ratified before July 2, 2025, the provisions of the current MOU generally would remain in effect as is required under the Ralph C. Dills Act. This analysis of the proposed agreement fulfills our statutory requirement under Section 19829.5 of the Government Code. The administration has posted on the California Department of Human Resources’ (CalHR’s) website the agreement, a summary of the agreement, and a summary of the administration’s estimates of the proposed agreement’s fiscal effects.

Background

This section provides background on key elements of collective bargaining for Unit 6 that are relevant to the proposed agreement.

Unit 6 in Context of State Workforce

Represents Significant Share of State General Fund Payroll. As of March 2025, rank-and-file and excluded employees associated with Unit 6 totaled nearly 30,000 full-time equivalent (FTE) employees, accounting for 12 percent of the about 256,000 FTE across the entire state workforce. Unit 6 rank-and-file and affiliated excluded employees account for 29 percent of the state’s General Fund salary and salary-driven benefit costs.

Furloughs

Long History of Using Furloughs to Address State Budget Problems. Furloughs, referred to as Personal Leave Program (PLP) when established through the state’s collective bargaining process, are the most common tool adopted by the state to reduce state employee compensation costs in times of budget problems. Furloughs have been used in nine fiscal years since 1992 (1992-93, 1993-94, 2003-04, 2008-09 through 2012-13, and 2020-21). Typically, a furlough for state employees reduces state employee pay by 4.62 percent in exchange for one day (eight hours) off per month without affecting other elements of compensation (for example, pension and health benefits). In the past, the state has (1) imposed furloughs and negotiated PLP at the bargaining table, (2) established furloughs as mandatory days when employees do not work (state offices would be closed one, two, or three “Furlough Fridays” each month), and (3) allowed employees to have “self-directed” furlough days where employees have discretion to use furlough days as they would vacation or other leave benefits. During the most recent period of furloughs in 2020-21, the state negotiated agreements with all 21 bargaining units to reduce employee compensation costs through PLP 2020 in anticipation of a budget problem in 2020-21 that did not materialize. The pay reduction and number of leave hours received during PLP 2020 varied by bargaining unit, depending on the specific terms of each agreement. Subsequent labor agreements ended PLP 2020.

Unit 6 Subjected to Largest Number of Furloughs in Past. The most extensive use of furloughs to reduce state employee compensation occurred during the five fiscal years between 2008-09 and 2012-13. While most state employees were subject to significant pay reductions during this period, Unit 6 was subject to the most furloughs and largest reductions during the period. In total, between 2008-09 and 2012-13, Unit 6 members received 94 furlough days—the most received by any of the 21 bargaining units. In comparison, most other state employees received 79 furlough days. As we discuss in our 2013 analysis, After Furloughs: State Workers’ Leave Balances, Unit 6 members’ pay was reduced through furloughs or PLP in 49 of the 60 months across the five fiscal years. In each of these months, Unit 6 members’ pay was reduced by between 4.62 percent and 13.86 percent. Between 2009-10 and 2010-11, Unit 6 members’ pay was reduced by 13.86 percent for 20 of the 24 months across the two fiscal years. As of December 2024, Unit 6 members have 131,427 hours of unused furlough or PLP hours in their leave balances.

Other Post-Employment Benefits (OPEB)

Rising Costs. OPEB in state employee compensation consists of retiree health benefits. The state has provided some form of health benefits to retired state employees since 1961. During most of this time, the state has paid for these benefits on a pay-as-you-go basis after an employee is retired and receiving the benefit. Since the 1990s, the costs for this benefit have been among the fastest growing costs in the state budget. Between 2000-01 and 2024-25, the state’s inflation-adjusted General Fund pay-as-you-go cost towards these benefits increased by more than 250 percent to $2.8 billion. The largest factors driving these cost increases have been (1) the rapid growth in health premiums and (2) the growing number of people receiving the benefit as more employees retire and people live longer in retirement.

Large Unfunded Liabilities. Because the state had not set aside funds to prefund retiree health benefits for much of the benefit’s existence, a large and growing unfunded liability exists. As of June 30, 2023, the state’s unfunded liability associated with this benefit for all state employees is estimated to be $85.2 billion.

Progress Towards Prefunding. In 2015-16, the state adopted a policy to establish through the collective bargaining process a prefunding arrangement whereby the state and current employees each pay one-half of the normal cost of the benefit (refer to our 2015 analysis, The 2015-16 Budget: Health Benefits for Retired State Employees for more information). (Under the policy, the state continues to make pay-as-you-go payments for benefits received by retirees.) The money contributed by the state and employees to prefund the benefit is put in a trust fund. Projections at the time indicated that the benefit would be fully funded by 2046. Under the plan, the assets of the trust fund cannot be used to pay for the benefit until 2046 or whenever the benefit is fully funded, whichever comes first. The state and Unit 6 agreed to this prefunding arrangement in 2016 with the fund expected to be fully funded for Unit 6 by 2048. Today, the state and employees represented by Unit 6 each contribute 4 percent of pay to prefund the benefit for Unit 6 members. As part of the PLP 2020 labor agreements, employees’ contributions towards OPEB prefunding were suspended during 2020-21; however, the state subsequently made a payment in 2021-22 to catch up for this loss of funding to the prefunding trust fund in 2020-21. As of June 30, 2023, the state and Unit 6 have set aside $1.7 billion in assets to prefund the benefit and the unfunded liability associated with Unit 6 is $15.4 billion. Based on the most recent valuation, the Unit 6 benefit remains on track to be fully funded by 2048.

Proposed Agreement

In this section, we summarize the major provisions of the proposed agreement.

Term. The agreement would be in effect through July 2, 2028. This means that the agreement would be in effect for three fiscal years: 2025-26, 2026-27, and 2027-28.

General Salary Increases (GSIs). The agreement would provide a 3 percent GSI on July 1, 2025 and another 3 percent GSI on July 1, 2027. A GSI adjusts the entire salary range for each classification represented by a bargaining unit, meaning that the pay increase applies to all Unit 6 members.

PLP 2025. The proposed agreement would establish a PLP 2025 for Unit 6 members under a new side letter (Side Letter #11). Under the PLP 2025 established by the agreement, employees’ pay would be reduced by 3 percent in 2025-26 and 2026-27. The PLP 2025 pay reduction offsets the 2025-26 GSI such that affected employees’ take-home pay essentially is flat during PLP 2025 relative to current salary levels. In each month during PLP 2025, most Unit 6 members would receive five hours of PLP 2025 leave credits (employees in specified Fire Captain classifications would receive seven hours of PLP 2025 leave credit each month). The proposed agreement also includes a new side letter (Side Letter #XX Regarding No Furlough) that specifies that Unit 6 would not be subject to administratively imposed furloughs during the term of the agreement—July 3, 2025 through July 2, 2028.

Suspension of Employer Contributions Towards OPEB. Under the agreement, the state would receive an OPEB prefunding holiday for two fiscal years. Specifically, for the duration of PLP 2025 (meaning in both 2025-26 and 2026-27) the state would not make its 4 percent of pay contribution to prefund Unit 6 retiree health benefits. The agreement would continue to require employees to make their 4 percent of pay contribution. There is no requirement in the agreement for the state to make a subsequent contribution to make up for the loss of funding to the prefunding trust fund.

Modifications to Existing Location-Specific Payments. The agreement makes changes to specified payments received by employees who work at specific locations. We describe these payments below.

Retention Differential for Hard-to-Keep/Fill Institutions. Under the current MOU, eligible employees at Salinas Valley State Prison; California State Prison, Sacramento; and R.J. Donovan Correctional Facility received payments of up to $10,000 over the course of the two years of the agreement—up to $5,000 in July 2024 and up to $5,000 in July 2025 depending on tenure. The proposed agreement similarly would provide eligible employees at the same institutions up to $10,000 over the first two fiscal years of the agreement with a payment of up to $5,000 in July 2026 and another payment of up to $5,000 in July 2027. Like the provision under the current MOU, the amount received by eligible employees would depend on the number of qualifying pay periods the employee worked in each fiscal year with eligible employees receiving $466.66 for each qualifying pay period worked in each preceding fiscal year.

Bonus for New Hires to Specified Locations. Under the current MOU, cadets at the academy who accept work at 1 of 13 specified facilities are eligible to receive a $5,000 location incentive bonus paid in two payments: the first $2,500 paid upon graduation from the academy and the second $2,500 paid 30 calendar days after reporting to the eligible institution. In order to receive the bonus, the MOU requires that the institution be 50 or more miles away from the cadet’s current home address and that the cadet is required to relocate from their current home address to work at the institution. The proposed agreement removes from the list of eligible institutions California Health Care Facility, California Medical Facility, Correctional Training Facility, and Substance Abuse Treatment Facility and State Prison (Corcoran). The nine institutions that would remain eligible under the proposed agreement include: Salinas Valley State Prison; California State Prison, Sacramento; R.J. Donovan Correctional Facility; Kern Valley State Prison; Pelican Bay State Prison; High Desert State Prison; San Quentin Rehabilitation Center; California State Prison, Los Angeles County; and California State Prison, Corcoran.

Housing Stipends. Under the current MOU, employees who work at San Quentin, Salinas Valley State Prison, and the Correctional Training Facility are eligible to receive $200 per month as a housing stipend. Effective the first day of the pay period following ratification, the proposed agreement specifies that Salinas Valley State Prison would no longer be eligible for the housing stipend. The agreement specifies that employees hired at the Correctional Training Facility by September 8, 2025 would continue to receive the housing stipend; however, employees hired after September 8, 2025 would not be eligible for the stipend. Under the agreement, employees at San Quentin would continue to be eligible to receive the payment.

Recruitment and Retention Incentive. Under the current MOU, employees who worked at Avenal State Prison, Ironwood State Prison, Chuckawalla Valley State Prison, Calipatria State Prison, Centinela State Prison, Pelican Bay, and High Desert State Prison were eligible to receive $1,300 after six months of work and another $1,300 after an additional six months (totaling $2,600 for working for 12 months at one of the specified institutions). The proposed agreement would again include this payment; however, it would change who would be eligible to receive the payments. Specifically, the agreement would (1) remove Chuckawalla Valley State Prison (because the facility was deactivated) from the list of eligible institutions; (2) add Salinas Valley State Prison to the list of eligible institutions; and (3) establish that employees hired after September 8, 2025 at Avenal State Prison, Calipatria State Prison, Centinela State Prison, and Ironwood State Prison would not be eligible to receive the payment.

Health Benefits. The agreement would increase state contributions towards employee health benefits to maintain the current proportion of average premiums paid by the state.

LAO Comments

Administration’s Estimated Fiscal Effect

Agreement Reduces Costs in 2025-26 and 2026-27, Increases Costs Thereafter. Figure 1 shows the administration’s estimated fiscal effect of the proposed agreement as well as the administration’s estimated fiscal effect of extending provisions of the agreement to excluded employees affiliated with Unit 6. Compared with spending levels today, the administration estimates that the agreement would result in General Fund savings of $120.2 million in 2025-26 and $69.8 million in 2026-27. After PLP 2025 ends and the state resumes making contributions to prefund OPEB, the administration estimates that the state’s annual General Fund costs would be $412.2 million higher than today.

Figure 1

Administration’s Estimated Fiscal Effect of Proposed Unit 6 Agreement

(In Millions)

|

2025‑26 |

2026‑27 |

2027‑28 |

||||||

|

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

|||

|

General Salary Increases |

$128.7 |

$128.7 |

$128.7 |

$128.7 |

$261.4 |

$261.4 |

||

|

Location‑Specific Payments |

2.2 |

2.2 |

16.2 |

16.2 |

15.8 |

15.8 |

||

|

Suspend Employer OPEB Contributions |

‑103.4 |

‑103.4 |

‑103.4 |

‑103.4 |

— |

— |

||

|

Personal Leave Program 2025 |

‑132.4 |

‑132.4 |

‑132.4 |

‑132.4 |

— |

— |

||

|

Health Benefits |

16.5 |

16.5 |

50.6 |

50.6 |

91.1 |

91.1 |

||

|

Extending Terms of Agreement to Excluded Employeesa |

‑31.8 |

‑31.8 |

‑29.6 |

‑29.6 |

44.1 |

44.1 |

||

|

Totals |

‑$120.2 |

‑$120.2 |

‑$69.8 |

‑$69.8 |

$412.3 |

$412.4 |

||

|

aThis is an indirect cost that would result from the agreement being ratified. |

||||||||

|

OPEB = Other Post‑Employment Benefits. |

||||||||

At May Revision, Administration Aimed to Achieve Budgetary Savings Through Reduced Employee Compensation Costs. The May Revision included a proposal to freeze pay for bargaining units with existing agreements and to achieve additional savings through bargaining or imposing terms for all 21 bargaining units. The proposed agreement with Unit 6 reflects this second goal. Should this agreement be ratified by the Legislature and CCPOA members, the resulting savings would help the state address the budget problem. As the administration is still negotiating with other bargaining units, however, whether the administration’s assumed savings will be achieved fully is yet to be known. As such, the Legislature will want to keep collective bargaining developments in mind as it finalizes the 2025-26 budget package. One option would be for the Legislature to withhold action on any collective bargaining agreement until all expected agreements have been submitted to the Legislature. This would allow the Legislature to ensure that all of the agreements collectively are consistent with the Legislature’s priorities. Depending on when the other agreements are transmitted to the Legislature, delaying legislative action beyond July 1, 2025 could result in an erosion to the savings identified by the administration.

Administration Does Not Estimate Effects on Overtime Costs. As is typical practice, the administration does not attempt to quantify the effects the agreement could have on state overtime costs. This approach is used because it can be difficult to estimate in a given year (1) the number of hours of overtime that will be worked and (2) the cost of each of those hours as the cost depends on which employees work overtime. That being said, overtime is a significant element of Unit 6 compensation and is an operational tool relied upon heavily by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR). In calendar year 2024, overtime among Unit 6 members cost $414.9 million—about 18 percent of the regular pay cost for Unit 6 during the same time period. Because overtime payments are based on an employee’s salary, the agreement could lead to higher overtime costs through higher salaries beginning in 2025-26. The number of hours of overtime worked also could grow as a result of this agreement to the extent that Unit 6 employees take more time off as a result of the PLP 2025 leave they receive under the agreement. We note that overtime costs in 2020-21 increased 12 percent compared with 2019-20; however, we cannot assess what share of this increase was due to PLP 2020, operational effects from the COVID-19 pandemic, or other factors.

Compensation Studies

Compensation Studies Can Be an Important Tool. A compensation study aggregates and analyzes internal and external data so that an employer can compare the compensation structure it offers with that provided by similar employers to similar employees. Employers in both the public and private sectors commonly conduct regular compensation studies to monitor changes in the labor market. A well-designed compensation study can be a valuable tool that provides a number of benefits that we identified in a 2023 analysis, including: allowing an employer to assess its competitiveness in the labor market, evaluating whether limited resources are being used efficiently, maintaining internal equity of compensation structures, bringing structure to compensation-setting decisions, and identifying possible recruitment and retention issues.

State Compensation Studies. In the past, state law required compensation studies to be produced six months prior to the expiration of an MOU. Following a recommendation from our office, Chapter 39 of 2023 (AB 130, Committee on Budget) amended Section 19826 of the Government Code to establish a regularly occurring cycle so that a new compensation study for each bargaining unit would be released every two years, regardless of the status of its MOU. The law required the first of these recurring biennial studies of Unit 6 to be released on February 1, 2025. CalHR issued the Unit 6 compensation study separately from the other compensation studies it released in 2025. Unlike the CalHR-developed methodology used for the compensation study of Units 2, 7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 16, 18, and 19, the Unit 6 compensation study uses a methodology that was agreed to at the bargaining table through a Joint Labor Management Committee process. We discuss the flaws of this methodology in greater detail below.

Long History of Issues With Unit 6 Compensation Study. We repeatedly have raised concerns about how CalHR evaluates Unit 6 compensation. We raised concerns in 2018 that CalHR provided no supporting evidence to justify Unit 6 pay increases despite it being required by state law (see our May 2018 analysis). We raised concerns in 2019 that CalHR withheld (and continues to withhold) a compensation study it completed in 2018 (see our June 2019 analysis) and proceeded to not produce compensation studies in 2019, 2020, or 2021 despite new agreements being submitted to the Legislature in those years (see our June 2021 analysis). When CalHR did release a compensation study of Unit 6 compensation in 2023 (referred to as the 2022 compensation study because it relies on data from 2022), we were highly critical of the methodology adopted for the study. For reasons we raised in our 2023 analysis, we found the 2022 compensation study to be flawed to the point that it was not helpful.

Newest Compensation Study Not Helpful. The Unit 6 study CalHR released in 2025 (based on 2024 data) suffers from the same methodological flaws that we identified with the 2022 study: the study omits overtime (a substantial component of Unit 6 compensation), compares Unit 6 compensation with a survey sample that is not representative of where state correctional officers work (largely reflecting regions with much higher wages and cost of living than where correctional officers work), and the study uses the wrong measure to compare the value of retirement benefits. For specific information about each of these findings, refer to our 2023 analysis. In short, similar to the 2022 compensation study, we find that CalHR’s 2024 Unit 6 compensation study is not helpful in assessing the state’s position as an employer of correctional officers across the state or where correctional officers work. We recommend that the 2024 study not be used to evaluate whether or not the state’s compensation for correctional officers is competitive.

Consider Changing Compensation Study Requirements Further. We think that the new biennial review of bargaining units’ compensation was a step in the right direction. However, the process can be improved further. In our experience, compensation studies that are developed using methodologies agreed to at the bargaining table have proven to be unhelpful in understanding how competitive the state is as an employer across the state or where state employees actually work. Studies designed by the bargaining table typically rely on non-representative samples of employers (for example, only comparing the state’s compensation with local government employers in high-cost coastal communities) and do not accurately compare total compensation across employers. We think that the Legislature needs an independent assessment of how the state’s compensation policies compare with those of other employers in the labor market in order to assess whether proposed changes in employee compensation are justified. To this end, we would encourage the Legislature to consider amending Section 19826 to ensure that the biennial studies are developed independently from the collective bargaining process. Specifically, whether a compensation study is prepared by CalHR or a third party, any decisions about design, methodology, preparation, conduct, and reporting of the study should (1) be developed without consultation with bargaining unit representatives and, instead, be the product solely of the study preparer; (2) result in compensation studies that are consistent across all 21 bargaining units in order to allow for comparisons of the state’s competitiveness as an employer across the state workforce; and (3) provide comparisons of the state’s compensation packages with those provided by other governmental employers (both county and federal) and private sector employers, when available The state and a collective bargaining unit should be able to agree to specific methodologies or designs for additional studies; however, any compensation study designed through the collective bargaining process should be in addition to the independently designed biennial study required by Section 19829.

Unit 6 Compensation

In the absence of a helpful compensation study, we look to other metrics to assess the state’s ability to recruit and retain correctional officers. We discuss those factors below. On the whole, the evidence supports the state continuing to be a competitive employer for public safety work.

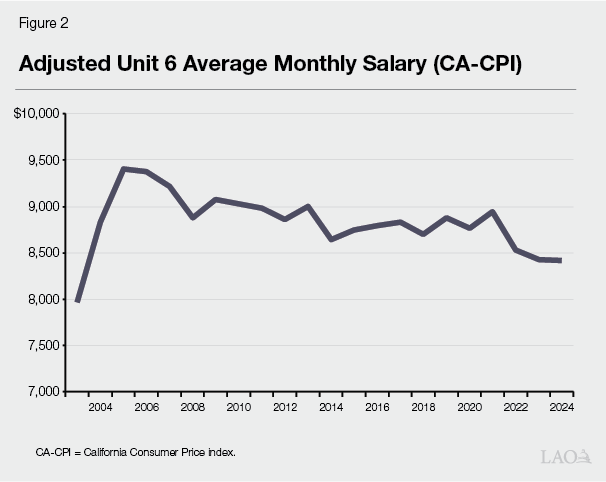

Unit 6 Base Pay Has Not Kept Pace With Inflation, but Remains Above 2003 Levels. As we discussed in our 2008 analysis, CDCR experienced high vacancies and recruitment challenges for correctional officers in the early 2000s that were addressed through operational changes as well as significant increases to correctional officer compensation provided by the Unit 6 MOU that was in effect from 2001 to 2006. In 2008, we indicated that “the job of state correctional officer may now be the most sought after in the California economy” thanks to the increase in compensation. Controlling for inflation, Figure 2 shows that average Unit 6 base pay increased by 18 percent between 2003 and 2006 under the terms of the 2001-06 MOU. (We note that average monthly base pay is an imperfect metric to gauge effects of inflation as it reflects growth in salary from salary increases as well as seniority as people move up their job classification’s salary range.) Since 2006, inflation has eroded the average Unit 6 base pay such that the average real monthly base pay in 2024 was almost 11 percent lower than it was in 2006. However, average real base pay remains 6 percent higher than it was in 2003 when the state last experienced significant challenges recruiting correctional officers.

Vacancy Rates Seem Within the Range of Normal for Unit 6. The vacancy rate across state civil service classifications has fluctuated in recent years from 15 percent in 2019 to 21 percent in 2023 to 17 percent as of May 31, 2025. Though much lower than statewide vacancy rates, the vacancy rate among Unit 6 classifications also has fluctuated from 8 percent in 2019 to 13 percent in 2023 to 9 percent as of May 31, 2025. Overall, current Unit 6 vacancy rates seem within the range of normal and do not signal extreme challenges in filling positions.

Number of Unit 6 Members in Decline. State policy has changed in recent years to result in a decline in the state correctional population (including people in prison and people on parole) and the closure of state prison facilities. This has resulted in a decline in the number of Unit 6 positions. For example, in March 2025, there were 24,498 FTE Unit 6 members—10 percent lower than the number of FTE Unit 6 members ten years ago in April 2015 (26,835). We expect the number of Unit 6 members to continue to decline. Both the 2025-26 May Revision and the budget approved by the Legislature under SB 101 (Wiener) assume that one prison will close by October 2026. Further, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a 6 percent decline in the number of correctional officers and bailiffs across the nation by 2033.

Turnover Among Staff. While there is some evidence that there has been turnover among correctional officers over the past decade, it does not seem to be to a degree that is problematic.

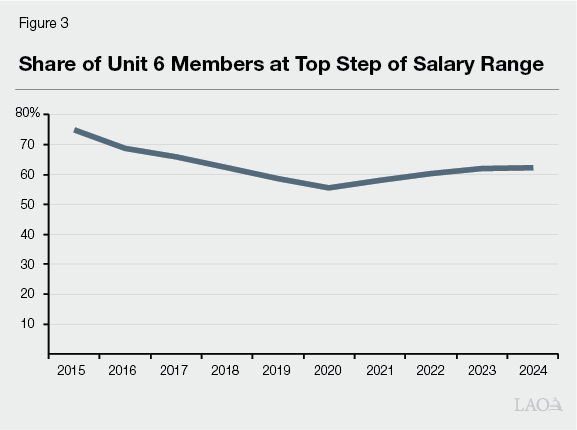

Somewhat Lower Share of Employees at Top Step. As Figure 3 shows, compared with 2015, a lower proportion of Unit 6 members are paid at the top step of their salary range. This indicates that there is less seniority among Unit 6 members than a decade ago. However, share of Unit 6 members at the top step has grown since 2020, suggesting that there is not a drain of seniority among Unit 6 members.

Younger Workforce. The median Unit 6 member in 2024 was five years younger than was the case in 2015. A younger workforce suggests that there has been turnover, likely resulting from older employees retiring.

Location-Specific Payments

Administration Provides No Supporting Evidence That Institutions Are “Hard to Fill.” The administration provides no evidence or justification to support the claim made by the agreement that the eligible institutions are hard to fill. Vacancy data from 2024 does not support the claim. In calendar year 2024, the average monthly vacancy rate across all CDCR facilities was 11 percent. The vacancy rate at each of the three eligible institutions was lower than this statewide average: 8.9 percent at R.J. Donovan Correctional Facility; 8.4 percent at California State Prison, Sacramento; and 6.1 percent at Salinas Valley State Prison.

Administration Provides No Justification for Payments for New Officers to Go to Specified Institutions. The administration provides no evidence or justification to suggest that the incentive payments for new officers at specified facilities are necessary to maintain an inflow of new recruits to those institutions. It is not clear that identified institutions are less desirable worksites for new recruits than other worksites.

Administration Provides No Evidence That Location-Specific Payments Under Current MOU Improved Recruitment or Retention at Identified Institutions. The administration has provided no evidence that the location-specific recruitment and retention payments established under the current MOU improved recruitment or retention efforts at the identified institutions over the course of the current MOU.

Effects of PLP

Furloughs a Common, but Imperfect Tool. As we indicated above, the state has used furloughs extensively in the past three decades in response to budget problems. Furloughs have some clear advantages including that they are administratively easy to implement; they offer immediate and predictable levels of savings; and they do not require a reduction in workforce, allowing the state to immediately “staff up” after the budget problem passes. However, there are some notable trade-offs to relying on furloughs to achieve budgetary savings. These trade-offs include effects on recruitment and growth in long-term liabilities. In terms of recruitment, furloughs can make the state a less attractive employer to possible new hires by making the state’s compensation package less competitive compared with compensation offered by other employers and by demonstrating a lack of predictability in the state’s terms of employment. In terms of growth in long-term liabilities, furloughs result in higher leave balances and retirement unfunded liabilities. Unless employees are able to take more time off—which is particularly challenging in 24-hour facilities, like prisons, where a certain number of employees must be at their post at any one time—furloughs result in larger unused leave balances. These higher leave balances, in turn, lead to higher costs to the state when employees separate from state service and the state must pay the employee for any unused leave at their final salary level. Retirement liabilities funded as a percentage of pay also grow as a result of furloughs. For example, the state pays a percentage of employees’ pay to fund pension benefits. During a furlough, the state’s contributions towards pension benefits is made as a percentage of the reduced salary. However, the benefit earned by the employee is based on their full (not reduced) salary. Accordingly, during furloughs, the state systematically underfunds its pensions—contributing to larger unfunded liabilities.

Suspension of Employer OPEB Contributions

Missed Opportunity to Improve OPEB Prefunding Arrangement. We long have been critical of the state’s retiree health prefunding strategy. We have found that establishing a benefit that fundamentally has no bearing on an employee’s salary to be funded as a percentage of pay is overly complicated and creates risk that the benefit will not be fully funded by the target date. In addition, sharing the funding cost with state employees likely strengthens any argument that the benefit is protected under the State Constitution, potentially preventing the Legislature from reducing or modifying the benefit in the future. Instead, we have argued that the state should assume the full responsibility of prefunding the benefit. While we are not at the bargaining table and do not know what issues were discussed, we feel it was a missed opportunity for the parties to not find a solution that simplified the prefunding arrangement while also helping address the current budget problem.

Suspending State Contributions Would Contribute to Growth in Unfunded Liabilities, Risk Goal to Fully Fund Benefit. The state’s funding plan for OPEB is less than ten years old. There are still 23 years remaining until the 2048 goal to have the Unit 6 benefit fully funded. Compounding interest is most powerful when it has more time to compound and grow. The administration estimates that suspending the state’s contribution to prefund OPEB for two years will reduce state costs by $206.8 million. If the agreement is not ratified, that $206.8 million would be invested in the prefunding trust fund and given the next two decades to grow. If the fund averaged an annual return of 5 percent over the next 20 years, the $206.8 million would more than double to nearly $550 million. Suspending the state’s contribution to prefund OPEB reduces costs today but contributes to a significant and growing unfunded liability and creates risk that the benefit will not be fully funded by 2048. Further, it creates a precedent for (1) other bargaining units this year to adopt similar actions and (2) future Governors to see this action as an acceptable trade-off to address future budget problems. To the extent that this action is repeated, whether this year or in future years, the goal to fully fund the benefit will become increasingly elusive. In that case, the state could once again face rapidly growing costs in order to pay this benefit.

Budget

Legislative Budget Package Rejected Similar Terms for Other Bargaining Units. As part of the May Revision, the administration proposed two new control sections (Control Sections 3.90 and 3.91, discussed in our May 2025 analysis) aimed at achieving budgetary savings through reductions in employee compensation. Through these control sections, the administration proposed that the state achieve savings through collective bargaining or imposition of terms by (1) not implementing pay increases scheduled under existing MOUs and (2) achieving an unspecified level of savings through unspecified policies to reduce employee compensation. The Legislature rejected both of these control sections as part of its approved budget.

Ratifying Agreement Likely Will Set Precedent for Other Units. There are seven bargaining units, including Unit 6, with ratified MOUs that are scheduled to expire by July 2, 2025. Unit 6 is the largest of these bargaining units. As such, whatever is ratified under a Unit 6 agreement will create a precedent that likely will be used as a model for successor agreements with the other six bargaining units expected to come to the table this year. Further, the Legislature and Governor have not yet agreed to a final budget package. If control sections similar to those included at May Revision are included in the final budget, this agreement could serve as a precedent for any policies that the administration might impose on any of the other 20 bargaining units (whether they have an active MOU or not).

Three-Year Term Could Reduce Future Legislative Flexibility. We long have recommended that the Legislature only ratify agreements that would be in effect for one or, at most, two fiscal years. The basis of this recommendation is to preserve legislative flexibility to respond to changing economic conditions. If the state’s budget condition were to improve or degrade over the next three fiscal years, it would be difficult for the Legislature to deviate from the agreement.