October 24, 2025

Considering Medi-Cal in the Midst of a Changing Fiscal and Policy Landscape

- Introduction

- Background

- Federal Medicaid Provisions and Their Effects

- Issues for Legislative Consideration

- Conclusion

- Companion Infographic

Executive Summary

Medi‑Cal Faces Major Changes Due to a Shifting Fiscal and Policy Landscape. After a decade of significant expansions, Medi‑Cal, California’s Medicaid program, faces a new fiscal and policy landscape. California’s fiscal situation has tightened while Medi‑Cal costs are rising, prompting the Legislature to enact a series of reductions to Medi‑Cal in June 2025. Following these actions, Congress enacted H.R. 1 in July 2025, which significantly changes federal Medicaid eligibility and financing policies. These federal changes will result in many billions of dollars in lost federal funding and place new workload demands and costs on providers, counties, and the state, with state costs alone potentially up to several billion dollars annually. H.R. 1 also could result in over 1 million people exiting from Medi‑Cal, though the exact level of disenrollment is uncertain. As such, we raise the following three key questions for legislative deliberation.

How Should H.R. 1 Provisions Be Implemented? The changes prompted by H.R. 1 create a number of implementation decisions for the state. For example, the state must decide how to adjust a tax on health plans, historically a key source of financial support for Medi‑Cal. The tax is expected to notably shrink under new H.R. 1 rules and existing state law, creating a few billion dollars of cost pressure for the state General Fund. The Legislature, however, could choose to adjust the health plan tax to generate a similar amount of revenue, but at higher cost to California health plans and their consumers. H.R. 1 also creates new eligibility requirements, largely centered on adults without children. The law grants states some flexibility around implementing these requirements, with the potential to exempt more people from the rules and mitigate disenrollments. We recommend the Legislature conduct early oversight of the administration’s implementation decisions and provide policy direction for implementation through legislation.

What Changes May Be Needed to Eligibility, Benefits, and Financing? The state does not have fiscal capacity to backfill all of the lost federal revenue resulting from H.R. 1. Moreover, given the state’s fiscal condition, absorbing the additional General Fund costs from the federal policy changes may not be feasible. As such, the Legislature will want to consider how to balance Medi‑Cal eligibility, benefits, and financing moving forward. Changes to Medi‑Cal will come with key policy trade‑offs around access, costs, and other priorities that the Legislature will need to weigh.

How Can the State Respond to the Increase in the Uninsured Population? Many of the people who exit Medi‑Cal as a result of H.R. 1 likely will face barriers to obtaining alternative sources of coverage, potentially leaving them without a source of comprehensive health insurance. There are no simple state interventions to address these barriers. Renewing county indigent health programs—a key source of coverage for low‑income populations prior to the recent Medi‑Cal eligibility expansions—would require significasnt fiscal restructuring. H.R. 1 also bars many people who are disenrolled from Medi‑Cal from receiving federal subsidies in California’s health insurance exchange. Moreover, the potential for expanding employer‑sponsored coverage may be limited, in part, because some who exit Medi‑Cal will do so because they do not work enough to meet new federal eligibility requirements. Given these challenges, the Legislature likely will need to explore new approaches, pursue creative solutions, and rebalance its fiscal and programmatic priorities.

Introduction

Over the last decade, the state has taken steps to expand eligibility, benefits, and provider payments in Medi‑Cal, California’s Medicaid program. These expansions were prompted by additional federal funds—largely through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA)—and generally sustained state tax revenue growth. Medi‑Cal, however, is entering a new landscape. Costs have exceeded expectations and due to structural budget deficits, the state enacted several reductions to Medi‑Cal during the 2025‑26 budget cycle. Following these actions, in July 2025, Congress enacted legislation that makes changes to Medicaid. This legislation—H.R. 1—reduces federal support to California in various ways, likely resulting in further reductions to the Medi‑Cal program.

This report aims to assist the Legislature as it responds to this changing landscape. We begin with background on the Medi‑Cal program, the major programmatic expansions over the last decade, and the recent pullbacks of some of these expansions. Next, we describe the major changes in the new federal legislation and analyze the associated programmatic and fiscal effects in California. We conclude with key issues and questions for the Legislature to consider in the coming months and years.

Background

Medi‑Cal Basics

In this section, we (1) provide an overview of the Medi‑Cal program and (2) describe how Medi‑Cal is funded.

Overview of the Medi‑Cal Program

Medi‑Cal Provides Health Care Services to Low‑Income Californians. Like Medicaid programs in other states, Medi‑Cal covers health care for low‑income Californians. The program covers a range of services, such as doctor visits, hospital and nursing facility stays, mental health care, substance use disorder treatment, and dental services. Medi‑Cal is a major source of health care coverage in California, with almost 15 million people (over one‑third of all Californians) estimated to be enrolled in 2025‑26.

Medi‑Cal Is a State‑Federal Partnership. The state and the federal government share programmatic and fiscal responsibilities for Medi‑Cal. The federal government created Medicaid and imposes program requirements on states, such as covering a minimum set of services and certain populations. The state, in turn, is responsible for implementing Medi‑Cal. California has chosen to go beyond the minimum federal requirements, such as by covering optional services and expanding eligibility to additional populations (many of which come with matching federal funds). California has also received waivers from certain federal rules over the years, generally to test new approaches for serving beneficiaries and delivering care.

Medi‑Cal Provides Services Through Multiple Systems. The primary way that Medi‑Cal delivers services to beneficiaries is by contracting with public and private health plans (known as the managed care system). The state provides these plans monthly payments to enroll Medi‑Cal beneficiaries, while the plans, in turn, arrange and pay for the health care of their enrollees. In some cases, however, the state reimburses providers directly under a fee‑for‑service system. This applies to certain services (such as pharmacy benefits) and some populations not enrolled in managed care.

Counties Also Have a Key Role in Medi‑Cal. In addition to the federal and state governments, counties also perform a few key functions in Medi‑Cal. Counties determine eligibility for Medi‑Cal applicants and also provide services, such as behavioral health care and personal care. Some counties operate their own hospitals, clinics, and other health facilities, which serve Medi‑Cal beneficiaries (in addition to other low‑income people).

Medi‑Cal Finance

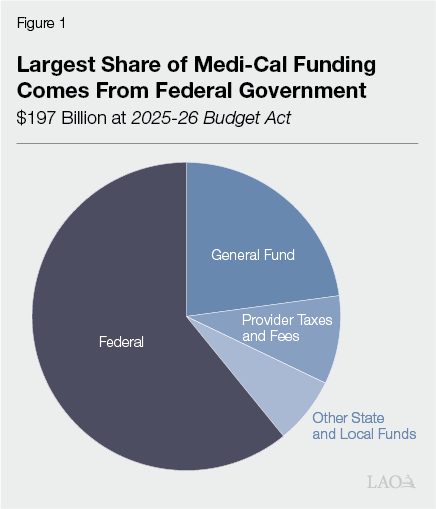

More Than Half of Medi‑Cal Funding Comes From Federal Matching Funds. In 2025‑26, the Medi‑Cal budget is estimated to be $197 billion, making it the largest program in the state budget in terms of total funds. As Figure 1 shows, federal funds comprise more than half of this amount. Specific matching formulas determine the overall federal share. In most cases, California’s federal matching rate is 50 percent (meaning that every state or local dollar spent generates one federal dollar). In some cases, however, the federal share is higher or lower. Services for childless adults, for example, receive a 90 percent federal match, whereas abortion services do not qualify for any federal match.

General Fund Is the Next Largest Source… California covers the nonfederal share of Medi‑Cal costs primarily through the General Fund. Medi‑Cal accounts for about 15 percent of General Fund expenditures in a typical year, making it the second largest allocation after K‑14 education.

…Followed by Provider Taxes and Fees… Like most states, California helps fund its Medicaid program using provider taxes and fees. These taxes and fees assess charges on certain kinds of health care providers (such as health plans and hospitals) for the services they deliver to Medicaid and non‑Medicaid patients. The state has long used provider taxes and fees to draw down more federal funds while imposing little net cost on the providers themselves. The way this works is complex. In general, some of the additional federal funds help to cover costs for providers or support supplemental provider payments. As a result of this arrangement, much of the cost ultimately falls on the federal government. The federal government limits its costs by imposing a number of rules on the size and scope of such taxes and fees. As Figure 2 shows, California has four provider taxes and fees, two of which are particularly large in terms of net revenue: a tax on health plans and a fee on private hospitals.

Figure 2

California Has Four Provider Taxes and Fees

|

Tax or Fee |

Charged Providers |

Approximate Annual Revenue |

General Use |

|

Managed Care Organization Tax |

Health plans |

Around $7.5 billion (net)a |

Increased Medi‑Cal provider rates and General Fund savings. |

|

Hospital Quality Assurance Fee |

Private hospitals |

Over $5 billionb |

Supplemental Medi‑Cal payments to private hospitals and General Fund savings. |

|

Long‑Term Care Quality Assurance Fees |

Long‑term care facilities |

Around $700 million |

Portion of state cost of long‑term care facility reimbursement rates. |

|

Ground Emergency Medical Transport (GEMT) Quality Assurance Fee |

Private GEMT providers |

$55 million |

Increased Medi‑Cal payments to private ground emergency transport providers and General Fund savings. |

|

aReflects revenue that is directly available to the state for higher provider rates and General Fund savings. bDoes not reflect proposed increase to fee, bringing annual to around $10 billion, that is pending federal approval. |

|||

…And Other State and Local Funds. California has turned to other sources as well to cover Medi‑Cal costs. For example, voter‑approved tobacco taxes over the years have helped to support and expand Medi‑Cal. Local governments also help cover the cost of certain Medi‑Cal services, such as behavioral health care and public hospital services.

Recent Medi‑Cal Expansions and Pullbacks

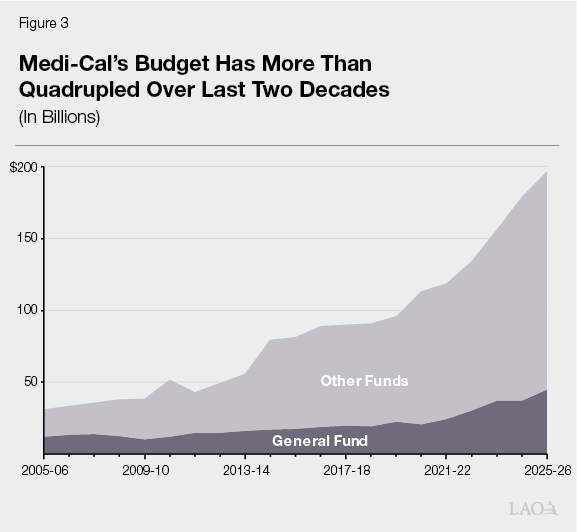

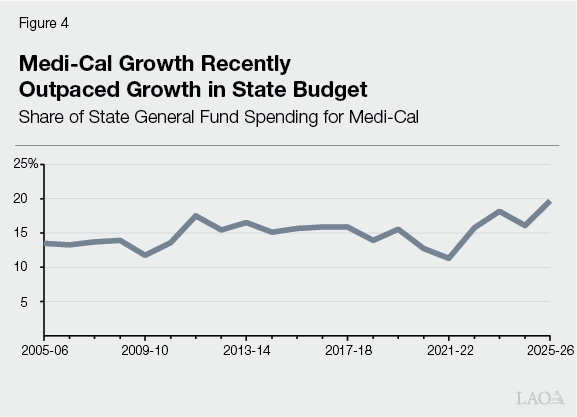

As Figure 3 shows, the Medi‑Cal program has grown over the past two decades, more than quadrupling on a total fund basis. As Figure 4 shows, this growth recently outpaced the growth of the state’s General Fund budget after generally keeping pace in previous years. While some of this growth is due to certain underlying factors, such as state demographic changes, much of it was driven by policy changes expanding program eligibility, provider payments, and benefits. In this section, we (1) discuss these expansions and (2) describe recent state decisions to pull back some of the expansions in light of budgetary constraints.

Major Expansions

Over Last Decade, State Expanded Medi‑Cal Eligibility for Three Key Populations. In several recent years, California has undertaken major eligibility expansions in Medi‑Cal. These expansions primarily affect three populations, described below.

- Childless Adults. Historically, low‑income, childless adults were not eligible for Medi‑Cal. Following Congress’s enactment of the ACA in 2010, California opted to extend eligibility to this population in 2014. The federal government initially covered 100 percent of the cost of the expansion, with this share eventually falling to 90 percent. Today, nearly 5 million Medi‑Cal enrollees (33 percent) are estimated to be in this population.

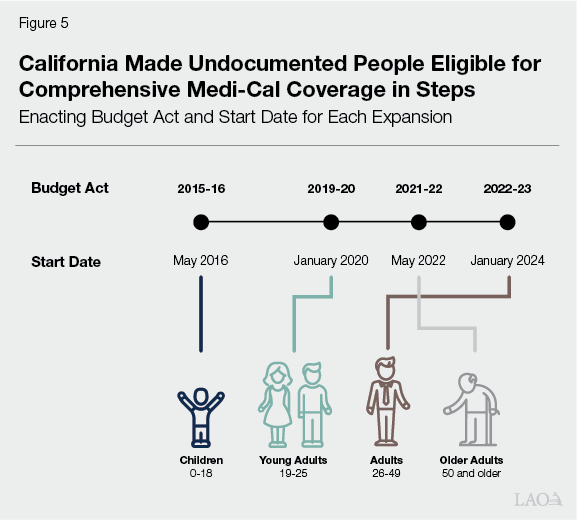

- Undocumented People. Federal Medicaid funding is restricted when services are provided to immigrants. Only certain groups of immigrants‑such as permanent residents meeting any applicable waiting period requirements—qualify for federal cost sharing for all Medicaid services. The remaining groups—deemed by federal law as having unsatisfactory immigration status (UIS)—are only eligible for federal cost sharing for limited services, including emergency and certain pregnancy‑related care. In California, the largest UIS group is undocumented people. In recent years, the state extended eligibility for comprehensive coverage to undocumented people. Because these additional services are not eligible for federal funding, the state has covered the entire cost of these expansions using General Fund. As Figure 5 shows, the state gradually phased in the expansions over time, prioritizing certain age groups first. Today, 1.7 million Medi‑Cal enrollees (11 percent) are estimated to be undocumented and have comprehensive coverage. (The state had already made other UIS groups—primarily documented immigrants residing in the United States for less than five years—eligible for comprehensive coverage many years prior.)

- Seniors and Persons With Disabilities With Assets. Historically, Medi‑Cal eligibility for seniors and persons with disabilities was subject to asset limits in addition to income limits. The asset limit varied by household size and excluded certain properties (such as a household’s primary residence and vehicle). In July 2022, the state increased the asset limit (for a household of one, from $2,000 to $130,000), and then in January 2024, eliminated it entirely. Our recent report, The 2025‑26 Budget: Understanding Recent Increases in the Medi‑Cal Senior Caseload, estimated that the latter change increased Medi‑Cal caseload by about 100,000 people.

State Used Flexibilities to Mitigate Significant Disenrollments. During the COVID‑19 pandemic, the state generally paused redetermining eligibility for Medi‑Cal enrollees. This meant that new people continued entering the Medi‑Cal program while very few existing enrollees exited, resulting in historically high caseload. The state enacted this policy as a condition of receiving enhanced federal funding. This federal condition ended in March 2023, prompting resumed redeterminations. To mitigate substantial disenrollments, the state enacted certain federally allowed flexibilities, such as automated renewal for certain enrollees. These flexibilities expired at the end of June 2025, likely leading to more substantial disenrollments from Medi‑Cal over the next several months.

Voters Have Expanded Funds for Medi‑Cal Provider Rate Increases… California voters have approved three ballot measures focused on increasing Medi‑Cal provider reimbursement rates to improve access to health care. Two of the measures—Proposition 52 (2016) and Proposition 35 (2024)—made California’s private hospital fee and health plan tax permanent, setting aside funds specifically for provider rate increases. For more information on Proposition 35, see our recent publication The 2025‑26 Budget: MCO Tax and Proposition 35. The third measure—Proposition 56 (2016)—increased taxes on tobacco products and directed most of the associated revenue to the Medi‑Cal program.

…As Has the Administration. State law also allows the administration to increase certain funds for provider rates, and in recent years it has exercised this authority. The administration is currently seeking approval from the federal government to draw down more federal funding by increasing the private hospital fee and local spending from public hospitals. These actions would result in higher payments to hospitals in 2025. Some of these increases are intended to help cover higher costs to hospitals from a legislatively mandated increase in the minimum wage for certain health care workers (Chapter 890 of 2023 [SB 525, Durazo]).

State Has Adopted Certain Other Additional Benefits. California has adopted certain other new benefits over the last decade. Many are part of a series of major federal waivers collectively called California Advancing and Innovating Medi‑Cal (CalAIM). The most notable of these new benefits provide specialized case management and certain non‑health supports, and target Medi‑Cal’s medically neediest, costliest populations. Some new benefits are tied to CalAIM’s limited‑term waiver authority and are contingent on federal waiver renewal.

Recent Pullbacks of Expansions

Costs of Some Expansions Are Significantly Higher Than Originally Estimated. The Medi‑Cal program’s complexity and size make it challenging to predict the cost of new policies with precision. Accordingly, the cost of some of the recent expansions have exceeded original estimates. Most notably, the undocumented persons eligibility expansions are estimated to be $10 billion General Fund annually (around one‑quarter of total General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal)—more than double the initial estimates. The cost of the asset limit elimination also is more than double initial estimates, with General Fund spending for this policy change estimated to be around $700 million annually. Generally, these higher costs have been driven by greater‑than‑expected caseload and service utilization.

Due to Fiscal Constraints, Recent Budget Act Pulled Back Some of These Expansions. Many of the above expansions occurred when the state’s General Fund revenue was growing. In recent years, however, the state’s fiscal situation has tightened, resulting in budget problems (when the General Fund does not have enough money to cover costs). The state is also projected to face ongoing deficits in the future. These trends, along with the higher‑than‑expected Medi‑Cal costs, prompted the Legislature to pull back some of these recent expansions. We describe some of the major pullbacks below.

Undocumented Adults’ Eligibility for Comprehensive Coverage Will Be Frozen. Beginning in January 2026, eligibility for comprehensive coverage for undocumented adults and seniors will be frozen. (Eligibility for children—those under 19 years old—will remain open for new enrollment.) This means that only the adults who already have comprehensive coverage as of December 31, 2025 will continue to have access to this level of coverage. Newly enrolled adults, as well as those who lose coverage after January 2026, will only be allowed to access limited coverage for emergency and certain pregnancy‑related care. This policy change is expected to reduce undocumented enrollment in comprehensive coverage, as people over time drop off Medi‑Cal and cannot re‑enroll in comprehensive coverage.

Beneficiaries With UIS Will Have to Pay Premiums. Beginning in July 2027, adults with UIS (including undocumented adults) will be required to pay a $30 monthly premium to remain enrolled in comprehensive coverage. The premium will only apply to adults aged 19‑59. This policy is expected to add to the disenrolling effect of the undocumented persons’ freeze, as some undocumented beneficiaries may be unable or unwilling to pay the premium, losing comprehensive coverage and remaining permanently barred from re‑enrolling in it.

Asset Limit Is Returning. Beginning in January 2026, the state will reinstate an asset limit for seniors and persons with disabilities. The limit will return to the level that existed from July 2022 through December 2023 ($130,000 for an individual). Given that the elimination of this asset limit increased Medi‑Cal’s senior caseload, its reinstatement will likely reduce caseload among this population.

Federal Medicaid Provisions and Their Effects

In this section, we provide an overview of the key federal changes to Medicaid and describe their programmatic and fiscal effects in the California context.

Overview of Federal Changes

Recent Federal Legislation Makes Numerous Changes to Medicaid. In July 2025, Congress passed and the President signed H.R. 1—titled the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. This legislation includes about $1 trillion in federal Medicaid reductions over ten years, representing the most significant changes to federal Medicaid policy since the ACA.

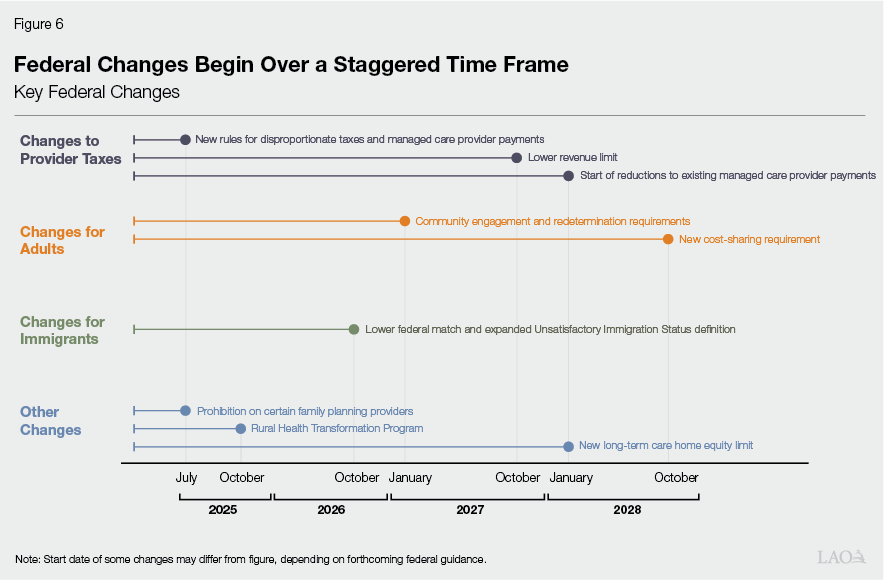

More Detail on Changes Are Emerging. As Figure 6 shows, only a handful of changes under H.R. 1 took effect immediately. The legislation sets out a schedule for the remaining changes to be implemented over the next few years. For many changes, their full effects will depend in part on forthcoming guidance from federal regulators, as well as state implementation decisions. As a result, our descriptions and analyses of these changes are preliminary and subject to change as more details become available.

Changes Generally Fall in Three Key Areas. While H.R. 1 includes numerous changes to Medicaid, most of these changes generally fall into three key categories: (1) changes to provider tax rules, (2) changes to eligibility and cost‑sharing requirements for adults, and (3) changes affecting immigrant populations. Below, we provide a more detailed description of each category, as well as some additional changes falling outside these categories.

Changes to Provider Tax Rules

Notably Scales Back Use of Provider Taxes. A key way that H.R. 1 achieves sizable federal savings in Medicaid is by scaling back states’ use of provider taxes. While these taxes will still be allowed under H.R. 1, states will need to follow new stricter rules limiting their use. Below, we describe the key changes.

Further Limits Disproportionately Taxing Medicaid Services. Under H.R. 1, states can no longer use certain strategies to disproportionately tax Medicaid services relative to non‑Medicaid services. This issue matters from a federal perspective because disproportionate taxes tend to result in higher federal costs. While federal rules already limited disproportionate taxation, many states—including California—were able to levy them. This is because states could adopt approaches that still met federal mathematical tests that measured disproportionality. Under H.R. 1, states are now prohibited from using some of these approaches, effective July 2025. The legislation allows the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to grant states up to three years to comply.

Gradually Reduces Revenue Limit Over Time. H.R. 1 also scales back states’ use of provider taxes by ratcheting down an existing revenue limit. The current limit—set at 6 percent of a taxed provider group’s overall net patient revenue—is intended to prevent states from adopting very large taxes and imposing high costs on the federal government. Beginning in Federal Fiscal Year 2028, this limit will decline gradually over time until reaching 3.5 percent in Federal Fiscal Year 2032. This 3.5 percent requirement only applies to states that expanded Medicaid coverage to childless adults as part of the ACA (such as California). For non‑expansion states, provider taxes will remain frozen at their current levels so long as they meet other requirements.

Reduces Allowable Managed Care Directed Payments to Providers. Under H.R. 1, states will face tighter limits in the amount of money they can direct to providers in their managed care systems. States often fund their share of these directed payments using provider taxes, thereby drawing down federal funds at no cost to their general funds. For states that implemented the Medicaid expansion to childless adults (such as California), the new limit will be the comparable rate paid in the federal Medicare program. (For non‑expansion states, the limit will be 110 percent of the comparable Medicare rate.) Previously, the allowable limit was the average rates health plans pay in the commercial sector, which tend to be higher than Medicare rates. The lower limit became effective in July 2025. However, the measure allows states in certain cases to gradually ramp down their existing payments to the new limit beginning January 2028.

Changes for Adults

Affects Adults, Particularly Those Without Children, in a Number of Ways. Another key area of focus for H.R. 1 is adults enrolled in Medicaid, especially those without children. From a fiscal perspective, childless adults are among the most expensive population for the federal government because of the relatively high federal share of cost (90 percent). Below, we describe some of the key H.R. 1 changes affecting adults.

Requires Community Engagement to Maintain Eligibility. Beginning at the end of 2026, nondisabled, childless adults enrolled in Medicaid must comply with a new community engagement requirement. To remain eligible, they will need to verify that they have completed at least 80 hours per month of work, education, or community service. Some groups will be exempt from the requirement (such as recently released inmates), and states can adopt certain other exemptions for people facing medical or economic hardships.

Increased Frequency of Eligibility Determinations. H.R. 1 also increases the frequency with which states must redetermine eligibility for childless adults. Currently, states generally redetermine eligibility every 12 months. Beginning January 2027, H.R. 1 requires states to redetermine eligibility for childless adults every six months.

Requires Cost‑Sharing for Certain Services. Beginning in 2028, childless adults with incomes above 100 percent of the federal poverty level will face new copayments of up to $35 per service for certain Medi‑Cal benefits. Previous Medicaid law allowed, but did not require, states to impose cost‑sharing requirements on select populations. The new requirement will only apply to childless adults earning more than 100 percent of the federal poverty limit. Certain services, such as primary care and behavioral health care, are excluded from the requirement.

Changes for Immigrant Population

Changes Rules for Immigrant Population. H.R. 1 further accomplishes federal savings by changing rules around federal funding for comprehensive coverage and limited coverage (pregnancy and emergency‑related care). We describe these changes below.

Adds More Immigrant Groups to UIS Population. H.R. 1 narrows the definition of which immigrant groups are considered to have satisfactory immigration status, generally limiting eligibility to lawful permanent residents. These new rules exclude some populations previously deemed to have satisfactory status, such as refuges and asylum grantees. These groups will now effectively be considered to have UIS, meaning that most of the services provided to them will not qualify for federal matching funds (outside of limited coverage).

Reduces Federal Funding for UIS Childless Adults. H.R. 1 also reduces the federal matching rate for emergency services provided to childless adults with UIS. As with childless adults who have satisfactory immigration status, the federal government currently pays 90 percent of emergency care costs. Beginning in October 2026, the federal government will only pay the state’s regular federal match rate (50 percent in California) for these services.

Other Key Changes

Prohibits Enforcement of New Eligibility Rules. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) previously adopted two rules intended to streamline eligibility and enrollment processes, such as by verifying income and assets using electronic data. The first rule (finalized in 2023) applied to people dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid, while the second rule (finalized in 2024) applied to the rest of the Medicaid population. H.R. 1 prohibits federal administrators from enforcing the elements of these rules that have not yet gone into effect, giving states greater flexibility to decide whether to implement the streamlined processes. The prohibition on enforcement will remain in effect until October 1, 2034.

Creates New Home Equity Limit for Long‑Term Care. Seniors and persons with disabilities apply for Medicaid under a separate set of rules that typically include a verification of assets. Starting in January 2028, H.R. 1 requires people who qualify for Medicaid under certain rules and use long‑term care to prove that their home equity is no greater than $1 million to remain eligible. This amount will not be adjusted for inflation over time. Although California has historically excluded an applicant’s primary residence when verifying assets, H.R. 1 removes states’ ability to exercise this option.

Prohibits Family Planning Funds for Certain Abortion Providers. H.R. 1 prohibits federal Medicaid payments to certain nonprofit entities that provide abortions and that received at least $800,000 in Medicaid payments in 2023. These entities cannot receive federal Medicaid funds for any health care services. As written in H.R. 1, this prohibition would be in effect from July 2025 until July 2026.

Requires Additional Eligibility Verifications. H.R. 1 requires states to take additional steps to verify Medicaid eligibility using administrative data. Specifically, states must create standardized processes to confirm enrollees’ mailing addresses using certain data sources. States must also submit enrollees’ social security numbers to CMS monthly so that the federal administration can check for duplicate enrollment across states. Additionally, states must conduct quarterly reviews to ensure that deceased individuals do not remain enrolled in Medicaid.

Provides Additional Funding for Rural Providers. H.R. 1 creates the Rural Health Transformation Fund, which will allocate $50 billion in state grants over five years (beginning in Federal Fiscal Year 2026) generally to support rural health providers. States must use the grants for a specified list of approved activities, such as provider payments, technology assistance, chronic disease prevention and management, substance use disorder treatments, clinician recruitment, and value‑based care models. The federal administration will allocate half of the $10 billion available per year equally among states. This means that each state will receive $100 million annually for five years (assuming that all states apply and receive approval). The federal administration will allocate the remaining half of funds to at least one‑quarter of all states based on criteria to be determined by the HHS Secretary. These criteria must include the share of a state’s population located in a rural area, the share of rural health facilities nationwide located in a state, and the status of hospitals in the state.

Programmatic and Fiscal Effects

Impact to Medi‑Cal Beneficiaries and Caseload

Millions of Medi‑Cal Enrollees Likely Would Be Subject to New Eligibility and Cost‑Sharing Rules. Most of the new Medicaid rules primarily apply to childless adults. This population is estimated to comprise around 5 million people, or around one‑third of Medi‑Cal’s total caseload. A portion of this population could be exempt from some of the new policies as specified in H.R. 1. Even with these exemptions, the number of people who fall within these rules likely will be in the millions.

Though Many Affected Enrollees Already Appear to Work… Past research has found that many adults in Medicaid work, with the remainder reporting certain barriers (such as caregiving responsibilities) to seeking employment. Based on limited data, more than half of affected Medi‑Cal beneficiaries already meet the new community engagement requirement through a mix of work and education.

…Evidence Suggests Many Will Disenroll Due to Administrative Burden. Even though many enrollees already work or attend school, the new community engagement requirement likely will result in many disenrollments. Some social service programs (such as CalFresh) already include work requirements, and a few states previously experimented with such requirements in their Medicaid programs. The research on these efforts suggests two key effects. First, the policies generally did not increase employment, resulting in disenrollment among unemployed beneficiaries. Second, many of those who were already working failed to adequately prove compliance and were disenrolled from their programs. This is likely because these beneficiaries found the new eligibility processes—which included additional verification requirements—too administratively burdensome. In California, another challenge is that the state and counties have little experience—or systems for—tracking beneficiary work and education as a condition of eligibility in Medi‑Cal.

Increased Redetermination Frequency Also Likely Will Result in Disenrollment. The move to a six‑month redetermination period likely will further decrease the childless adult caseload. In part, this is because the new process will more quickly identify beneficiaries whose household income rises above the eligibility threshold. Some eligible beneficiaries also may struggle to demonstrate their eligibility at the higher frequency due to administrative burden.

Total Level of Disenrollment Is Uncertain. While it is likely that the new eligibility policies will result in some level of disenrollment, the magnitude of this effect is uncertain. Much of the impact will depend on how the state implements the new rules. Given this uncertainty, we considered independent analyses that model the Medicaid disenrolling effects of the provisions in H.R. 1. For example, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has provided its own national disenrollment projections. Allocating CBO’s estimates of the eligibility‑related changes to California (based on California’s share of national Medicaid enrollment), we estimate that Medi‑Cal disenrollments across all Medicaid changes in H.R. 1 could be around 1.2 million people.

Most Disenrolled People Likely Would Become Uninsured. Many independent analyses (including those from CBO) project that the vast majority of people disenrolled from Medicaid as a result of H.R. 1’s provisions would become uninsured, rather than find alternative kinds of coverage. This is because other forms of coverage are likely not available to this population. For example, most disenrolled adults probably lack access to employer‑sponsored health coverage since their typical work patterns—part‑time or seasonal—limit their access to such coverage. H.R. 1 also disqualifies certain people disenrolled from Medicaid from qualifying for federally subsidized premiums in state health insurance exchanges, like Covered California.

Cost Sharing for Beneficiaries May Decrease Utilization. The requirement for states to implement cost sharing may reduce utilization of certain services, though there is significant uncertainty about the magnitude. Research suggests that copays can have substantial effects on utilization, and that some kinds of services (such as pharmacy) may be more sensitive than others. In Medi‑Cal, however, the effects of copays have been more uncertain. In large part, this is because Medi‑Cal providers could not refuse services to patients who did not pay their required out of pocket share. The state eliminated required copays a few years ago to simplify service delivery. Compounding this uncertainty, the state has significant discretion in how it implements cost sharing requirements under H.R. 1, lending to many possible outcomes.

Impact to Medi‑Cal Providers

Health Plan Tax May Become Very Small… Under the new provider tax rules, the tax on health plans likely will be much smaller than under current law. This is because the state would have to significantly reduce tax rates to make the Medi‑Cal and commercial tax rates proportional. The tax rate on Medi‑Cal enrollment ($274 per member, per month in 2025) is more than 100 times the tax rate on commercial enrollment ($2 per member, per month in 2025). Proposition 35, however, limits the size of the tax on commercial enrollment to nominal amounts. (The box below provides more information on Proposition 35’s interaction with federal rules.) As a result, the health plan tax under H.R. 1 likely will raise tens of millions of dollars annually, rather than the billions of dollars it currently generates.

How Proposition 35 Interacts With Federal Law

Makes Tax Permanent, Conditioned on Federal Approval. California has charged a specific tax on health plans (known as the Managed Care Organization Tax) for more than a decade. Proposition 35, approved by voters in 2024, made this tax permanent in state law. The measure, however, conditions the state’s ability to charge the tax on receiving federal approval. Federal approval, which typically is required every few years, is important because it enables the state to use the tax to draw down more federal funds for Medi‑Cal. Accordingly, if the state fails to obtain federal approval, the health plan tax—as well as Proposition 35’s requirements on spending the associated funds—is not in effect.

Allows Changes to Tax to Meet Federal Requirements… Federal regulators have periodically changed rules around approving provider taxes, sometimes requiring the state to restructure the health plan tax. Proposition 35 anticipates this dynamic. Specifically, though the measure makes the tax’s existing structure permanent, it also requires the state to amend it to comply with any future federal rule changes.

…Except for Key Limit on Tax on Commercial Enrollment. While the state has broad authority to change the health plan tax’s structure to comply with federal rules, there are certain limits. Most notably, the measure generally limits the tax rate on commercial enrollment to around its existing size ($2.50 per monthly enrollee, with an annual revenue cap of $36 million and some room to slightly exceed these amounts). This provision envisions the state’s current practice of generating revenue primarily from the much larger tax rate on Medi‑Cal enrollment. This is because the Medi‑Cal tax rate generates revenue to the state by drawing down more federal funding, whereas the commercial tax rate falls on health plans and their consumers to pay.

…Resulting in Much Smaller Augmentations for Providers. Under Proposition 35, most of the money from future health plan taxes must go to provider rate increases and other augmentations. While some of these augmentations have already occurred, they were scheduled to notably increase beginning in 2027 had the health plan tax remained at its current size. With the tax expected to shrink, providers likely will not receive the larger augmentations planned for 2027.

Private Hospital Fee Also Could Decline Over Time… Federal policy changes also likely will result in a smaller private hospital fee, though for different reasons. Relative to the health plan tax, the private hospital fee is less disproportionately levied on Medi‑Cal services and has fewer constraints on the tax rates. (The box below has more information on Proposition 52’s requirements.) However, the most recent version of the fee in 2025—which is significantly larger than in prior years—has not yet received federal approval. If approved, the increase in the hospital fee likely would be limited term, with the fee ramping down over time to comply with the reduction in the revenue limit. If the federal government rejects the larger fee, then hospitals will not benefit from the anticipated programmatic increases that would otherwise result.

How Proposition 52 Works

Makes Private Hospital Fee Permanent. Similar to Proposition 35 (2024) and the health plan tax, Proposition 52 (2016) made a pre‑existing fee on private hospitals (known as the Hospital Quality Assurance Fee) permanent in state law. Similar to the health plan tax, the fee must be approved by the federal government every few years to draw down federal funds for Medi‑Cal. In contrast to Proposition 35, however, Proposition 52 does not place direct limits on the fee rates enacted on Medi‑Cal and non‑Medi‑Cal services. As such, the state has more flexibility to adjust the fee levels over time to comply with federal rules.

Fee Supports Hospital Supplemental Payments… As was the case prior to Proposition 52’s enactment, the private hospital fee primarily supports Medi‑Cal payments for hospital services. It accomplishes this purpose by receiving matching federal funds, with both federal funds and hospital fee revenue generally flowing back to private hospitals as payments. Most hospitals get more money back from this arrangement than they pay in fees. That said, some hospitals, particularly those that primarily provide care to non‑Medi‑Cal patients, incur net costs as a result of the fee program.

…And General Fund Offset for Medi‑Cal. A sizable portion of hospital fee revenue—typically around one‑quarter each year—helps offset General Fund spending on Medi‑Cal. Proposition 52 effectively locks the share of revenue in place permanently, ensuring that a majority of the fee revenue directly benefits private hospitals that pay the fee, rather than the General Fund.

…As Will Public and Private Hospital Managed Care Payments… Payments to hospitals in the Medi‑Cal managed care system also will decline over time. This is because of the required gradual reduction in managed care payments to the level paid in Medicare. At the time of this analysis, the Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) had not provided estimates of how Medi‑Cal hospital payments compare to Medicare. However, it is our understanding from discussions with stakeholders that some Medi‑Cal hospital payments are higher.

…Resulting in Funding Declines to Hospitals. In all, the reductions in the private hospital fee and managed care directed payments will result in less funding to hospitals over time. The magnitude, timing, and distribution of these funding losses, however, are uncertain.

Safety Net Providers Likely Will Face Higher Uncompensated Care Costs. Some of the impacts from Medi‑Cal caseload reductions and increases in the uninsured population likely will fall on safety net hospitals and clinics. This is because these providers have a statutory responsibility to provide health care to patients, regardless of ability to pay. These providers could have larger shortfalls in funding, as a greater share of services would come without full reimbursement (also known as uncompensated care). The magnitude of this impact is uncertain as it depends on the number of people that lose Medi‑Cal coverage, become uninsured, and still seek out services from safety net providers.

Impact to State

Federal Changes Create Three Key Direct Fiscal Effects to State General Fund. Taken together, H.R. 1’s changes to Medicaid will reduce federal funding for California. Some of these reductions will have direct effects on the state’s General Fund, either by increasing or reducing costs. Direct fiscal effects refer to nondiscretionary budgetary changes under federal and state law, rather than discretionary policy responses to H.R. 1’s provisions. (See the box below for more information on the distinction between our definition of direct fiscal effects and discretionary policy responses.) We estimate there will be three key direct effects, on net potentially costing as much as several billion dollars in annual General Fund costs.

- Cost to Backfill Lower Provider Tax Revenue. By far the largest direct cost to the state General Fund would come from lower provider tax revenue as a result of H.R. 1. The health plan tax and private hospital fee currently support the Medi‑Cal program, and H.R. 1 provisions will reduce funding from both sources. Absent changes to Medi‑Cal, the state would need to backfill much of this lost funding. This cost could be in the low billions of dollars annually.

- Reduced Spending From Lower Medi‑Cal Enrollment and Service Utilization. Another key fiscal effect to the state would be from disenrollments due to the new eligibility policies. Generally, these policies would result in less spending. This is because caseload is a key driver of Medi‑Cal costs, and reductions in caseload result in lower spending. Despite the potential for large disenrollments, however, General Fund savings likely would be limited, potentially reaching into the hundreds of millions of dollars. Most of the total savings (likely in the billions of dollars) would instead accrue to the federal government, which pays for most of the cost to enroll childless adults. The new cost‑sharing requirements also could reduce utilization of certain services, though this effect is uncertain and depends on how the state implements the requirements.

- Cost to Backfill Lost Federal Funding for Certain Immigrant Populations. There also would be direct state costs from the changes affecting immigrants. This is because less federal funding would be available to cover costs for this population. The fiscal effect could be significant. For example, we estimate the reduction in federal funding for emergency care services alone could cost around $1 billion annually in state funds. However, the cost could be less if immigrant caseloads decline due to the enrollment freeze, new state‑imposed premiums, or evolving federal immigration policies.

Defining Direct Fiscal Effects

For the purposes of this report, we define direct fiscal effects as costs or savings to the General Fund required under H.R. 1 and existing state law. Absent changes in state law, the General Fund will either have to cover these costs or will experience fewer costs. For example, reductions in federal matching funds require a backfill from the General Fund to maintain service levels, thereby increasing state costs. Conversely, disenrollments due to new community engagement requirements will reduce state costs.

Importantly, our estimates assume that most of the lost federal funding from H.R. 1—which could be as much as tens of billions of dollars—do not place costs directly on the General Fund. Instead, these broader costs will depend on discretionary policy choices by the Legislature. For example, much of the lost federal funding would come from caseload reductions associated with the new community engagement requirements. Caseload reductions result in lower costs to the state. Backfilling this lost federal funding, such as by creating a new state‑only program for people disenrolled from Medi‑Cal, would be a discretionary choice and a substantial change in existing state policy.

Estimates of Net Costs Are Imprecise… The above fiscal impacts are challenging to precisely estimate. They depend in part on forthcoming federal guidance and state implementation decisions that are currently unknown.

…and Their Timing Remains Uncertain. In addition, the time line for some key changes remains uncertain. Most notably, when the state will need to comply with the new disproportionality rule for provider taxes is uncertain. This is because H.R. 1 begins this new requirement in July 2025, but allows the HHS Secretary to grant states up to three years to comply. Compounding this uncertainty, the HHS had already proposed related draft guidance to states in May 2025, before Congress enacted H.R. 1. This draft guidance suggested that California, as well as a few other states, would have to adjust its provider taxes relatively quickly. In light of Congress’s enactment of H.R. 1, however, which provides somewhat different time lines than envisioned in the proposed guidance, the due date for California to adjust its taxes is difficult to project.

State Budget Has Constrained Capacity to Address H.R. 1’s Cost Pressures. Notwithstanding many Medi‑Cal cost pressures from H.R. 1 facing the Legislature, the General Fund already is expected to face a deficit in 2026‑27 and subsequent fiscal years. The 2026‑27 deficit, projected to be $17 billion as of June 2025, was estimated before Congress passed H.R. 1. While our assessment of the state’s budget condition will be updated in November, recent state tax collections have improved since budget enactment. This gain, however, likely reflects an exuberant stock market, with the rest of the economy appearing fragile. With the federal legislation now finalized and the state already projected to have ongoing deficits, the Legislature likely cannot cover all of these costs from existing General Fund resources while maintaining the current level of service in the Medi‑Cal program.

Federal Changes Also Place More Administrative Workload on the State. The state will need to undertake significant action to implement many of the H.R. 1 required changes to Medi‑Cal. For example, DHCS will need to translate federal changes into practical guidance for health plans and counties, as well as provide technical assistance to affected entities. In some cases, the federal changes may require updates to information technology (IT) systems to implement them. The extent of these administrative costs is unknown.

Impact to Counties

Counties Will Face Costs From New Workload Demands… Counties are the primary administrators of eligibility determinations in Medi‑Cal and will be responsible for implementing many of the eligibility changes in H.R. 1. These changes, along with the recent end of the redetermination flexibilities from the COVID‑19 public health emergency, may significantly increase the amount of hours county staff spend on processing eligibility determinations.

…and Losses as Medi‑Cal Providers. In addition to their administrative responsibilities, counties provide certain Medi‑Cal services (like behavioral health services for high‑needs individuals) and some operate hospitals, clinics, or other health facilities. As such, many counties could face the same funding challenges as other Medi‑Cal providers discussed earlier. In particular, county‑run safety net facilities would see reduced revenue as they treat more uninsured individuals.

Magnitude of Costs Is Still Emerging. Though county costs from H.R. 1 are likely, the total effect across the state is uncertain. Counties and other stakeholders were still reviewing H.R. 1’s provisions and potential effects when we spoke to them earlier this year. That said, costs likely will vary significantly across counties.

Issues for Legislative Consideration

In this section, we raise three key issues for the Legislature to consider: (1) how to implement the changes to Medi‑Cal under H.R. 1, (2) how to consider the Medi‑Cal program in light of these changes and state fiscal constraints, and (3) how disenrollments from Medi‑Cal might affect other sources of health care coverage.

Implementing Federal Changes

How Should the State Restructure Provider Taxes?

Legislative Action Could Preserve Large Health Plan Tax by Shifting the Tax Burden. Once it is time to comply with the new disproportionality rules, the greatest changes likely will be needed for the health plan tax. Though current law generally will require this new tax to be much smaller, there is a way the state could maintain a similar level of revenue as today (before the required reduction in the revenue limit under federal law). Proposition 35 allows the Legislature to amend its provisions with a three‑fourths vote in each house, so long as the amendment furthers the measure’s intent and purpose. Thus, the Legislature potentially could amend the measure’s limit on taxing commercial enrollment, enabling the state to have a large and proportionate tax. Such an action would ensure the state could continue to draw down significant federal funds to support Medi‑Cal, a key goal of Proposition 35. That said, as the box below explains, increasing the commercial tax would shift more costs onto California health care consumers.

How a Large, Proportionate Health Plan Tax Could Be Structured

Higher Commercial Tax. To make the health plan tax more proportional, the state would have to increase the tax rate on commercial enrollment and decrease the tax rate on Medi‑Cal enrollment. In effect, this would place more cost onto private health insurance and, therefore, its consumers. Using the enrollment base of the existing health plan tax, we estimate that an around $30 per‑member, per‑month tax rate on both Medi‑Cal and commercial enrollment would generate around the same net revenue as the current tax. This is higher than the current commercial tax rate ($2.25 per‑member, per‑month) and lower than the current Medi‑Cal tax rate ($274 per‑member, per‑month).

Increased Costs for Health Care Consumers… Though health plans would pay the higher commercial tax, plans likely would try to pass on most or all of the cost of the tax onto their members. They would do so by increasing premiums, which in 2024 averaged over $600 per month. The increase in premiums (around 5 percent, on average) could have a variety of effects. For enrollees with employer‑sponsored coverage, much of the cost of higher premiums would fall on employers. Employers in turn might respond in a number of ways, such as offering employees less generous health benefits, shifting costs onto employees, or reducing employment. People who purchase health insurance themselves generally would pay the higher premiums.

…But Also Continued Federal Match. While California health care consumers and workers would bear a larger portion of a proportionate health plan tax, some of the cost would still fall on the federal government. We estimate the federal share would be around 35 percent to 40 percent. Put another way, every $1 generated by a California consumer would yield around $0.60 federal funds. While considerably lower than in the existing disproportionate tax, this matching rate is far higher than what the state accomplishes with most other taxes, which do not generally directly draw down more federal funds.

Many Potential Adjustments to Private Hospital Fee. In contrast to the health plan tax, the state has a wider array of choices to make with the private hospital fee. This is because Proposition 52, which provides the parameters for the fee, does not limit fee levels on hospital services provided to people with commercial insurance. The measure also grants the state the ability to adjust the fee program to comply with federal rules. While facing fewer legal hurdles, having a large, proportionate private hospital fee raises other policy trade‑offs. A higher fee on commercial services could increase costs on some hospitals, particularly those with fewer Medi‑Cal‑funded services. By contrast, a lower fee on Medi‑Cal services could reduce the amount of fee revenue, reducing payments to hospitals and funding to the state.

How Should the State Implement Eligibility and Cost‑Sharing Requirements?

State Could Track Work Completion Through Income. Though federal Medicaid law will now require most nondisabled, childless adults to complete 80 hours of community engagement each month, H.R. 1 grants states certain flexibilities to track beneficiary compliance. Most notably, states can determine compliance via employment using an income‑based approach, rather than a work‑hour approach. Under the income‑based approach, enrollees will be required to earn at least $580 each month—the federal minimum wage ($7.25 per hour) multiplied by 80 hours. Using an income‑based approach could result in fewer disenrollments relative to an hours‑based approach. Primarily, this is because DHCS might be able to gather income data through existing sources, reducing needed documentation from members and administrative workload for counties. In addition, because California’s minimum wage ($16.50 per hour for most employers in 2025) is notably higher than the federal minimum wage, some Californians might meet the income threshold before meeting the 80‑hour threshold.

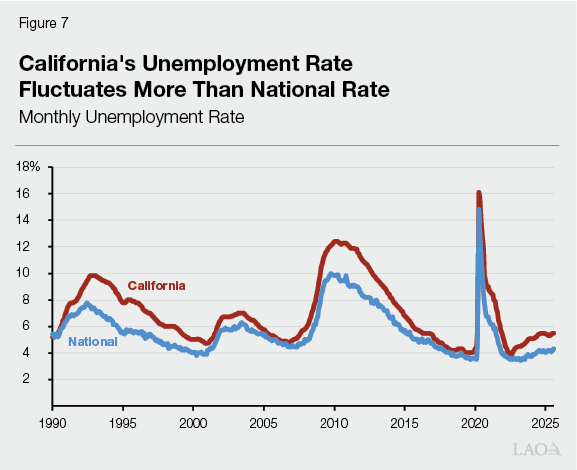

State Could Exempt More Adults From Community Engagement Requirements. The federal legislation also allows states to exempt additional populations from community engagement requirements. These exemptions likely would apply to a nontrivial number of people from the requirement altogether. Under one of the likely more impactful exemptions, states can choose to exempt Medicaid members that reside in a county with high unemployment rates relative to the national average. Based on July 2025 unemployment data, about 20 counties in California currently meet the criteria, and several more are close. We estimate that this additional exemption alone could exclude at least a few hundred thousand individuals.

Enhanced Federal Funds Could Assist With State IT Needs. To implement new eligibility requirements, the state likely will need to adjust its Medi‑Cal eligibility IT systems. The extent of needed changes would depend on some of the implementation choices the state makes. CMS has indicated that states might be eligible for enhanced federal funding to upgrade their Medicaid IT systems in response to H.R. 1. As such, the Legislature likely will want to better understand the needed changes, the time line for DHCS to adopt these changes, and the potential to offset some of these costs using enhanced federal funding.

Expanding Flexibilities Could Limit Disenrollments at Relatively Low State Cost… Each of the eligibility flexibilities granted to states could limit the number of people who are disenrolled from Medi‑Cal. Available evidence suggests that work requirements in welfare programs fail to increase employment among beneficiaries while disenrolling some who already participate in the labor market. Also, while disenrollments will result in some state savings, these savings will be fairly limited. Instead, most of the savings would accrue to the federal government, which covers most of the cost of services for childless adults in Medi‑Cal. Given the low cost‑effectiveness of imposing work requirements, maximizing the use of H.R. 1’s flexibilities to minimize the policy’s disenrolling effects would be reasonable.

…But Potentially With Added Complexity. Adding more flexibilities also could come with the potential downside of more complexity for beneficiaries and counties. For example, exempting high unemployment counties from work requirements could create more volatility. This is because employment trends vary considerably month to month. As Figure 7 shows, California’s unemployment rate tends to have larger rises and falls than the national rate. At the county level, trends are considerably more volatile, with some counties consistently higher than the national rate but others quite varied month to month. The extent of this issue, however, depends on how often the federal government will require the state to redetermine this exemption.

State Could Consider Many Ways to Structure Cost‑Sharing Requirements. The state also has some flexibility to structure the new cost‑sharing requirements. While H.R .1 requires states to have cost sharing on certain services up to $35, lower amounts are allowable. The state could impose relatively minimal copays to mitigate the cost to enrollees who are at or near the poverty level and could struggle to pay the charges. The state also could structure copays in ways that promote high‑value care, such as by adopting higher charges for less medically necessary services. These decision points will affect the impact on utilization and associated savings.

How Can the Legislature Weigh in on These Implementation Decisions?

Recommend Legislature Consider Two Key Questions at Oversight Hearings. With key implementation decisions forthcoming, the Legislature likely will want to conduct early and frequent oversight hearings on H.R. 1 during next year’s session. Policy and budget committees likely will want to engage in oversight, given H.R. 1’s fiscal and policy implications for the Medi‑Cal program and the choices facing DHCS. With this in mind, we recommend the Legislature consider two key questions regarding implementation:

- What Are the Objectives? For any implementation decision, the Legislature could first consider its overarching objectives. For example, on cost sharing, should the state aim to minimize costs on beneficiaries? Or should cost sharing strategically target lower‑value, less‑necessary services? Similarly, for provider taxes, should the state continue to maximize federal funds as much as possible? Or should the state minimize costs on providers and private health care consumers?

- What Are the Options to Accomplish These Objectives? After establishing its objectives, the Legislature could work with our office, the administration, and stakeholders to assess the various implementation options. State costs or savings, expected Medi‑Cal disenrollments, and administrative capacity will be key factors to consider when weighing each option. For example, the Legislature may want to work with the administration and counties to understand the administrative feasibility of tracking Medi‑Cal member incomes for compliance with the community engagement requirement.

Recommend Legislature Set Goals in Statute, Where Possible. Some of the implementation actions under H.R. 1 will require the Legislature to adopt conforming legislation. In other cases, DHCS may have sufficient authority to act without changes to statute. For example, DHCS has a fair amount of flexibility to adjust the private hospital fee, pursuant to Proposition 52. Nonetheless, in addition to conducting oversight, we recommend the Legislature adopt as many changes as possible into statute—even for those cases where such action is not legally required. Taking such action will better ensure that the administration, counties, and providers implement H.R 1’s provisions according to legislative intent.

Considering the Medi‑Cal Program

Legislature Likely Will Need to Revisit Goals for Medi‑Cal. In the last several years, the Legislature has sought to cover as many low‑income people as possible in Medi‑Cal, while also expanding services and certain reimbursement rates. In light of the state’s tight fiscal situation and the federal government’s changing policies, it is unlikely that the state can continue meeting all of these objectives at current service levels. As a result, the Legislature likely will need to balance its policy goals for Medi‑Cal.

Three Key Questions Will Drive Legislative Decision‑Making. In revisiting the Medi‑Cal program, the Legislature faces three key questions: (1) who should Medi‑Cal serve, (2) what per‑enrollee service level should Medi‑Cal provide, and (3) what non‑General Fund financing options are available? Of these levers, the state likely has the greatest potential for savings in Medi‑Cal eligibility. Given the complexity of these questions, we recommend the Legislature begin early conversations about its priorities during next year’s hearings, even before all of the H.R. 1 changes have gone into effect. Below, we expand upon each of these questions in greater detail to inform the Legislature’s deliberations over the coming months.

Who Should Medi‑Cal Serve?

Eligibility Is a Key Cost Driver in Medi‑Cal. Changes in eligibility—which have a direct effect on caseload—can have substantial fiscal implications for Medi‑Cal. All else equal, an increase in caseload results in higher Medi‑Cal spending. Certain populations are also costlier to serve than others, owing to their higher utilization of relatively expensive services and differences in federal fund matches.

Some Medi‑Cal Eligibility Rules Are Required, Whereas Others Are Optional. As a condition of receiving federal funds for their Medicaid programs, states must cover services for certain populations. Examples of these mandatory populations include children, parents, seniors, and persons with disabilities in households at or near the poverty level. As Figure 8 shows, however, states have the option under federal law to serve more populations and receive federal matching funds for services provided to them. Some of these populations, such as childless adults and children from higher‑income households, come with larger federal matches to encourage state coverage.

Figure 8

Some Medi‑Cal Populations Are Optional Under Federal Law

Examples of Key Medi‑Cal Populations

|

Mandatory |

Optional |

|

Children and infants |

Childless adults |

|

Parents and caretakers |

Higher‑income children |

|

Seniors |

Higher‑income people with medical need |

|

Persons with disabilities |

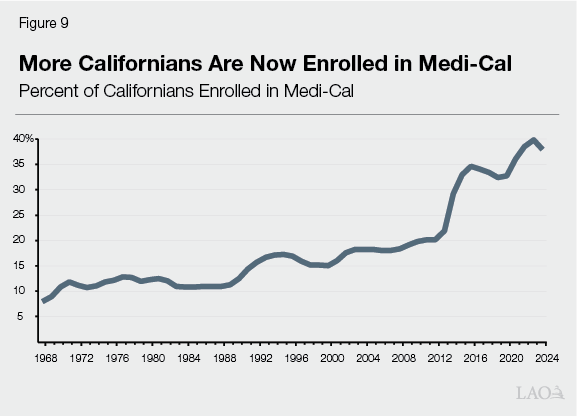

Generally, Medi‑Cal Eligibility Has Expanded Over Time. California has taken advantage of optional eligibility rules under federal law to notably expand Medi‑Cal coverage. When it was originally created in the 1960s, Medi‑Cal focused on coverage for people receiving cash assistance and the elderly and disabled. Over time, the state has made more low‑income populations eligible, with the cost in many cases shared with the federal government. As Figure 9, these expansions transformed Medi‑Cal from a relatively small program into one that serves more than one‑third of the state’s population.

Eligibility Expansions Focused on Expanding Coverage to More Populations… The Legislature primarily expanded Medi‑Cal eligibility to help more low‑income people access health care. Absent the current Medi‑Cal program, people at or near the federal poverty level would be more likely to be uninsured or have limited coverage. For example, low‑income populations that had long been excluded from Medi‑Cal, such as childless adults and undocumented people, were historically more likely to lack comprehensive health care coverage.

…And Simplifying Rules. The state has also sought to simplify and streamline eligibility rules. Medi‑Cal, like most state Medicaid programs, historically had a series of complex pathways for people to gain eligibility. This historical approach aimed to prioritize limited resources for the neediest and most vulnerable populations. However, the many pathways were difficult to navigate. Recent eligibility expansions helped address this issue, enabling more people to access coverage with less administrative burden. For example, our recent publication on the asset test elimination found that the action—which notably simplified eligibility rules—likely encouraged new seniors who were already eligible to enroll in Medi‑Cal.

Given Recent Fiscal Constraints, Rebalancing Eligibility Priorities Has Been a Key Focus. The state’s fiscal constraints have required the Legislature to turn to ongoing spending reductions. With several discretionary eligibility expansions in recent years, Medi‑Cal eligibility is a key area of focus. Accordingly, the Legislature already has scaled back some of the most notable and costly recent expansions in the 2025‑26 budget. Further reductions and associated savings may be achievable in the coming years. Such changes, however, raise key policy trade‑offs for the Legislature.

Four Key Factors to Consider Around Restricting Medi‑Cal Eligibility. Were the Legislature interested in pursuing further changes to Medi‑Cal eligibility, we recommend it consider four key factors:

- Need and Cost. Health care utilization is uneven, with a small share of people driving a majority of the needed services and associated cost. High utilizers tend to have chronic diseases, disabilities, or other factors that require regular interactions with the health care system. These populations therefore face the greatest health risks from loss of coverage. Reducing coverage for high utilizers, however, also yields the greatest potential for reducing costs.

- Relative Access. Some Medi‑Cal populations face particular barriers to accessing private health insurance coverage. For example, undocumented people are legally ineligible to work—limiting their access to employer‑sponsored coverage—and prohibited from receiving federally subsidized coverage in the health insurance exchange. Absent options for access to alternative health care coverage, some populations rely solely on state‑provided care.

- Federal Match. Certain populations come with different levels of federal matching funds, affecting their overall cost to the state. Some populations, such as childless adults and higher‑income children, come with higher federal matches and therefore less cost to the state. By contrast, services to the UIS population comes with less federal funding and therefore substantially higher state cost.

- Complexity. Adding new eligibility rules inherently adds complexity to Medi‑Cal, potentially discouraging affected populations from applying and remaining enrolled. More rules also can add administrative burden to counties. The Legislature likely will want to be mindful of this issue as it explores targeted eligibility changes in the context of simultaneous federally required changes.

What Per‑Enrollee Service Level Should Medi‑Cal Provide?

Benefits, Utilization, and Provider Rates Also Are Key Cost Drivers. After caseload, the other major cost driver in Medi‑Cal is spending per enrollee. Generally, there are three key factors that contribute to spending per enrollee: (1) Medi‑Cal benefits, (2) enrollee utilization of these benefits, and (3) reimbursement rates for services. Expansions or increases in any of these areas tend to increase Medi‑Cal spending.

Some Medi‑Cal Benefits Are Optional… Much like for eligibility rules, federal Medicaid law includes mandatory and optional benefits. As Figure 10 shows, California, like most states, has elected to cover many optional benefits for Medi‑Cal beneficiaries. The figure is not comprehensive—many more optional benefits exist in Medi‑Cal.

Figure 10

Many Key Medi‑Cal Benefits Are Optional

Examples of Mandatory and Optional Benefits in Medi‑Cal

|

Mandatory |

Optional |

|

Hospital stays and visits |

Prescription drugs |

|

Physician services |

Dental care |

|

Safety net clinic visits |

Hospice |

|

Nursing facility stays |

Physical and occupational therapy |

|

Home health care |

Private duty nursing |

…But Sometimes Difficult to Modify… In past years of fiscal constraint, the Legislature has considered scaling back certain optional benefits to achieve ongoing savings. One key challenge to this approach is that the most utilized optional benefits are major fixtures of the Medi‑Cal program. For example, while prescription drug coverage is optional in Medicaid, prescription drugs are central to modern medical care delivery. As a result, every state has elected to cover prescription drugs for beneficiaries. Eliminating pharmacy or other highly utilized optional benefits would likely limit enrollees’ access to quality health care. As another challenge, some Medi‑Cal populations have heightened federal requirements that include providing otherwise optional benefits. For example, the state must provide dental services to children, even though it is optional for other populations. The ACA also requires minimum coverage for childless adults, including some otherwise optional benefits (such as pharmacy).

…Or Often Relatively Inexpensive. Medi‑Cal also offers a number of smaller optional benefits, many of which the state added to Medi‑Cal over the last decade. The state has recently turned to some of these optional benefits for savings. For example, the Legislature defunded certain nonemergency dental benefits for adults during state budget shortfalls, and then resumed funding once the state’s fiscal situation improved. Continuing this approach, however, likely would yield limited savings. Past optional benefit reductions have resulted in a range of savings from millions of dollars to the low hundreds of millions of dollars. This is because these smaller benefits tend to have lower utilization.

State Has Limited Opportunities to Increase Utilization Management… Another potential way to limit spending in Medi‑Cal is by managing enrollees’ utilization of services. There are many tools that payors use to limit utilization, such as charging copays and requiring prior authorization of expensive services. The state’s ability to further constrain utilization in Medi‑Cal, however, likely is fairly limited. This is primarily because the state already delivers most Medi‑Cal services in the managed care system, in which health plans already are incentivized to avoid unnecessary care and limit utilization. For services that are outside of the managed care system, such as pharmacy benefits, the state already implements substantial utilization controls and is expanding these controls through actions taken in the 2025‑26 budget.

…Or Reduce Provider Rates. The state also has turned to provider rate reductions in past years to reduce Medi‑Cal spending. Reducing provider rates has the advantage of reducing Medi‑Cal spending without affecting eligibility or benefits. However, cutting provider rates could reduce some providers’ participation in Medi‑Cal, which could, in turn, limit patient access to certain services or in certain regions. Accordingly, federal rules require Medicaid provider rates to be adequate to ensure access to care. In recent years, CMS has heightened scrutiny around provider rates, including those paid by health plans. For example, the state has agreed to pay specific rates for certain services as a condition for approval of certain waiver authorities (see box below).

Medi‑Cal Provider Rate Requirements in Federal Waivers

In recent years, the federal government has conditioned approval for certain Medicaid waivers on California’s commitment to maintain provider rates at specified levels. In 2023, California agreed to pay for primary care, maternity care, and non‑specialty mental health services at 87.5 percent of the rate paid in the federal Medicare program to draw down more federal funds. The requirement applied to both the fee‑for‑service and managed care systems. Accordingly, the state adopted this new rate as part of the 2023‑24 budget. In 2024, the federal government tied this rate requirement to its approval of a substantial behavioral health waiver.

Four Key Factors to Consider Around Reducing Per‑Enrollee Costs. Were the Legislature interested in pursuing ways to reduce per‑enrollee costs, we recommend it consider four key factors.

- Health Needs of Medi‑Cal Beneficiaries. Medi‑Cal beneficiaries, who are by definition low income, face particularly acute health care needs relative to the rest of the population. These needs can raise key trade‑offs for the Legislature. For example, California recently stopped covering certain specialized weight loss drugs in Medi‑Cal to help address the budget problem. As we noted in our recent publication, The 2025‑26 Budget: Medi‑Cal Pharmacy Spending, these drugs are relatively costly and are not covered by most private insurance. Medi‑Cal beneficiaries, however, are more likely to be obese than the rest of the state. The Legislature had to weigh these factors in deciding to eliminate coverage.

- Adequacy of Provider Rates. The state has tended to take targeted approaches to adjusting provider rates. For example, recent increases focused on services (such as maternity care) where rates were particularly low relative to what the federal Medicare program pays. This is because less competitive rates can discourage providers from delivering timely care to Medi‑Cal patients. The Legislature could take a similar approach to any rate reductions, working with DHCS to identify services with higher rates relative to Medicare.

- Short‑ and Long‑Term Effects. Some actions conceptually could reduce costs in the short run, but lead to higher costs down the road. For example, the state spends tens of billions in General Fund dollars annually on home‑ and community‑based supports (such as in‑home supportive services), which are optional benefits. These supports, however, are in part intended to mitigate the demand for more expensive skilled nursing facility services, a mandatory benefit.

- Feasibility of Savings. Given the many limitations described earlier, the Legislature will want to ensure that any per‑enrollee cost reductions are realistic and the intended savings likely to materialize.

What Non‑General Fund Financing Options Are Available?

Some Key Financing Sources Have Become Increasingly Infeasible. Over the past two decades, the state has increasingly turned to sources other than the General Fund to help pay for Medi‑Cal. This approach has helped mitigate cost pressure on the General Fund without reducing underlying service levels in Medi‑Cal. California is not unique in this regard—most states rely on certain non‑General Fund sources to help pay for their Medicaid programs. In recent years, however, these sources have faced a number of constraints. Below, we describe these sources.

Provider Taxes Will Become a Smaller Part of Medi‑Cal Budget. Provider taxes have become the most significant source of state financing for Medi‑Cal outside of the General Fund. In the last few budget cycles, the Legislature has turned to the health plan tax to help address budget shortfalls. However, the interaction of Proposition 35 and H.R. 1’s new rules will constrain the state’s ability to maintain the health plan tax at its current level.

Tobacco Tax Revenues Are Steadily Declining. When voters approved Proposition 56 in 2016, it initially provided more than $1 billion annually to Medi‑Cal. These funds have declined over time, however. This is because tobacco product consumption has steadily declined in California—an intended effect of charging tobacco taxes. The state has since backfilled much of this decline from the General Fund.

Local Governments Likely Face Fiscal Constraints. The state has also increasingly turned to local governments to help pay for services. For example, counties and the University of California have increasingly covered the nonfederal share of cost of their hospital inpatient services. Because local governments will also be impacted by H.R. 1, it is uncertain whether the state could increase the local government share of cost to mitigate reductions to Medi‑Cal without imposing significant fiscal burdens on counties.

Two Factors to Consider Around New Financing Approaches. Given the above constraints, whether the Legislature could sustain the existing size of the Medi‑Cal program using new financing approaches is uncertain. To the extent it considers such approaches, however, we recommend the Legislature consider two key factors.