LAO Contact

September 6, 2019

MOU Fiscal Analysis: Bargaining Units 1, 3, 4, 11, 14, 15, 17, 20, and 21 (SEIU Local 1000)

Late August 30, 2019, the administration posted on the California Department of Human Resources’ (CalHR’s) website a 1,798 page tentative agreement between the state and the nine bargaining units represented by Service Employees’ International Union, Local 1000 (Local 1000). Local 1000 represents about one-half of the state’s rank-and-file employees. The administration has posted on the CalHR website a summary of the provisions of the agreement as well as the administration’s estimates of the annual costs resulting from the proposed memorandum of understanding (MOU). Our State Workforce webpages include background information on the collective bargaining process, a description of the state’s 21 bargaining units including the nine represented by Local 1000, and our analyses of agreements proposed in the past.

This analysis of the proposed MOU between the state and Local 1000 fulfills our statutory requirement under Section 19829.5 of the Government Code. At the conclusion of this analysis, we summarize the aggregate fiscal effects of this agreement as well as the proposed MOUs between the state and three other bargaining units waiting for legislative consideration (Bargaining Units 5, 7, and 13). If the Legislature ratifies these agreements, it will be establishing the state’s employee compensation policies under which a majority of state employees will work for the next few years. We recommend that the Legislature consider the agreements with all 12 of these bargaining units in the context of the state budget as they (1) have significant short- and long-term effects on the Motor Vehicle Account—a fund that recently was projected to be insolvent—and (2) interact directly with the enacted version of the 2019‑20 budget. The fiscal effects that are referenced in this analysis are relative to the state’s employee compensation costs assumed under current law.

Major Provisions

Term. Employees represented by Local 1000 currently work under an unexpired agreement that will remain in effect until January 1, 2020. Unless a provision specifies a different effective date, the term of the whole proposed agreement is from January 2, 2020 to June 30, 2023. This means that the agreement would be in effect for three and a half fiscal years (the second half of 2019‑20, 2020‑21, 2021‑22, and 2022‑23). However, the agreement contains a provision—related to employee contributions towards pensions benefits, discussed below—that would have a new fiscal effect in 2023‑24. The long duration of the proposed agreement is not consistent with our 2007 recommendation that the Legislature only approve tentative agreements that have a term of no more than two years.

Provisions Related to Pay

Three General Salary Increases (GSIs). The unexpired MOU provided employees represented by Local 1000 a 3.5 percent pay increase in July 2019. The proposed agreement would provide GSIs to all employees represented by Local 1000 on July 1 of 2020 (2.5 percent), 2021 (2 percent), and 2022 (2.5 percent). Combined, the administration estimates these GSIs will increase state annual costs by $710 million ($299 million from the General Fund) by 2022‑23.

Special Salary Adjustments (SSAs) for Specified Classifications. In addition to the GSIs discussed above, about one-fifth of employees represented by Local 1000 would receive an SSA on July 1, 2020. Most of the approximately 22,000 full-time equivalent employees (FTE) who would receive an SSA would receive a 5 percent pay increase; however, corporation examiners (about 170 FTE) would receive a 10.25 percent SSA. The administration estimates that these SSAs will increase annual state costs by $125 million ($35 million from the General Fund) beginning in 2020‑21.

Accelerated Increased Minimum Wage for Employees Represented by Local 1000. The current minimum hourly wage for employees represented by Local 1000 is $12 per hour and will increase to $13 per hour in January. The proposed agreement would increase the minimum wage for employees represented by Local 1000 to $15 per hour effective July 31, 2020. This means that the minimum wage for Local 1000 would increase to $15 per hour before the state minimum wage. (For reference, the current state minimum wage is $12. Under state law, the state minimum wage will increase to $13 per hour on January 1, 2020, to $14 per hour on January 1, 2021, and to $15 per hour on January 1, 2022.) In addition, the agreement would provide SSAs to classifications that currently are paid above $15 per hour but that will become “compacted” by lower-paid classifications with fewer responsibilities receiving the new minimum wage. (Salary compaction occurs when the differential between a lower-paid classification and a higher-paid classification is not large enough to attract employees to the higher-paid classification that has more responsibilities.) In total, affected employees would receive a pay increase ranging from less than 1 percent to more than 20 percent. The administration estimates that these pay increases would increase state costs in 2020‑21 by $25 million ($13 million from the General Fund), with a full annual effect beginning in 2021‑22 of $27 million ($14 million from the General Fund).

Pay Differentials for Specific Work, Conditions, or Skills. The agreement would increase the amount of money that employees represented by Local 1000 receive for doing specific jobs, working in specific regions, or using specific skills.

- Geographic Pay Differentials. The agreement would—beginning July 1, 2020—provide $250 per month to employees represented by Local 1000 who work in the Counties of Orange, Santa Barbara, Santa Cruz, or San Luis Obispo. In addition, the agreement would add personnel specialists who work in the County of Alameda to an existing recruitment and retention differential (Pay Differential Number 211)—increasing state costs in 2019‑20 by about $20,000. The administration estimates that these differentials will increase annual state costs by about $14 million (about $6 million coming from the General Fund) beginning in 2020‑21.

- Bilingual Pay Differential. Effective the first pay period following ratification, the agreement would double the pay differential received by employees who work in a bilingual position from $100 per month to $200 per month. The administration estimates that this would increase state costs in 2019‑20 by $5 million ($2 million General Fund) and $7 million in subsequent years.

- Correctional Case Record Series. Eligible Case Records Technicians and Correctional Case Records Analysts would receive an annual recruitment and retention differential of $2,400. The administration estimates that this will increase annual state costs by about $3 million, mostly from the General Fund.

- Investment Officer Performance Recognition Pay Differential. The agreement would expand the number of employees eligible to receive the incentive award administered by the California Public Employees’ Retirement System ((CalPERS) and California State Teachers’ Retirement System for investment officers. The award currently is available to Investment Officer IIIs. The agreement would allow Investment Officer IIs to receive the award. The administration estimates this would increase annual state costs by about $2 million beginning in 2020‑21—all paid from retirement funds.

- Call Center Pay Differential. Effective immediately following ratification, the agreement would increase the monthly differential received by employees at call centers from $100 to $150. This pay differential is considered pensionable compensation. The administration estimates this will increase state costs in 2019‑20 by $800,000 ($90,000 from the General Fund) and annual state costs by about $1 million in subsequent years.

- Nurses at State Special Schools (SSS). The agreement would provide the about ten FTE nurses employed at one of the state’s special schools for deaf or blind students a 5 percent pay differential. The administration estimates that this will increase annual state costs by about $50,000 beginning in 2020‑21.The administration assumes that state money appropriated through Item 9800 of the budget act would pay for this increased cost. In 2016, our office recommended that the Legislature assess the SSS funding formula to lower costs, improve fiscal incentives, and promote stronger accountability.

Increased Reimbursement for Commute-Related Expenses. The agreement would increase the amount of money that employees represented by Local 1000 receive to reimburse commute-related expenses by $35 per month. (Under the current agreement, employees are eligible to receive $65 each month for mass transit or vanpool riders and $100 if they serve as a vanpool driver.) The administration estimates that this would increase state costs by $4 million ($2 million General Fund) in 2019‑20 and $6 million annually in subsequent years.

Provisions Related to Health Benefits

Increased State Contributions to Unit 3 Member Health Benefits. For Unit 3 (Professional Educators and Librarians), the state contributes a flat dollar amount to employee health benefits. The flat dollar contribution amount was last adjusted in 2019. The proposed agreement adjusts the amount of money the state pays towards these benefits each year for the duration of the agreement. For the term of the agreement, the state’s contribution would be adjusted so that the state pays up to 80 percent of an average of CalPERS premium costs and up to 80 percent of average CalPERS premium costs for enrolled family members—referred to as the “80/80 formula.” (For the other eight bargaining units, the state pays a specified percentage of average premium costs, thereby allowing the state’s contributions to change automatically to maintain the 80/80 formula as premiums change.)

Monthly Payment for Employees Enrolled in CalPERS Health Plans. Beginning July 2020, each employee represented by Local 1000 who is the primary recipient of a CalPERS health plan would receive a monthly payment of $260 for 36 months. The payment would be subject to Medicare and (if applicable) Social Security payroll deductions, but would not be subject to CalPERS pension contributions. At the time of this publication, it was not clear whether or not union dues would be deducted from the payment. Any deductions to this payment reduces its effectiveness at offsetting employee contributions to health premiums. The dollar amount seems to be based roughly on the difference between the state’s contribution to two-party coverage under the 80/80 formula versus the 100/90 formula (where the state pays 100 percent of the average premium for the employee and 90 percent of the average premium cost for additional premiums). The relative benefit of this payment depends on an employee’s base pay. For example, while $260 constitutes about 8 percent of the average base pay for Unit 15 (Allied Service Workers) members, it constitutes only about 3 percent of the average base pay for Unit 17 (Registered Nurses) members. Although the stated intent of the payment is to improve access to and affordability of health care, the payment amount (1) is $260 for all eligible employees regardless of actual premium costs (for example, single coverage versus family coverage) and (2) does not increase as premiums increase.

Provisions Related to Retirement Benefits

Increased Employee Contributions to Pensions. Beginning July 1, 2023—the day after the agreement expires—employees represented by Local 1000 would contribute an additional 0.5 percent of pay towards the normal cost of their pension benefits. As a result, employees enrolled in the Miscellaneous pension benefit would contribute 8.5 percent of pay, Industrial members would contribute either 9.5 percent or 8.5 percent, and Safety members would contribute 11.5 percent of pay. This would result in employees paying about one-half (in most cases, slightly more than one-half) of the blended normal cost of their benefit.

Mandatory Overtime

Reaffirms Commitment to Reduce Use of Mandatory Overtime. In the current agreement as well as the proposed agreement, the administration and union “agree that mandatory overtime is not an effective staffing tool.” As we discuss below, however, the administration continues to rely on mandatory overtime for nursing staff at the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), California Department of Veterans Affairs (CalVet), and Department of State Hospitals (DSH). The proposed agreement puts in place greater limitations on the state’s ability to require employees to work mandatory overtime—for example, beginning January 2020, the agreement would reduce the number of mandatory overtime shifts an employee can be required to work in a month from five to four. The agreement also specifies that “over the term of this agreement the number of mandatory overtime shifts employees are required to work shall be reduced.” Specifically, the agreement requires the state to reduce the use of mandatory overtime by January 2020 and a second reduction by July 1, 2021. The agreement specifies that the second reduction may be deferred to July 1, 2022 if the state or the union do not mutually agree that reductions can be implemented successfully by July 1, 2021.

LAO Assessment

Administration’s Fiscal Estimate

Increased Annual State Costs of $1.1 Billion by End of Agreement. As Figure 1 shows, the administration assumes that the proposed agreement would increase annual state costs by $1.1 billion by the end of the agreement in 2022‑23. Although beyond the term of the proposed MOU, the administration provided fiscal estimates for the effect of the agreement in 2023‑24 because the agreement would increase employee pension contributions beginning 2023‑24.

Figure 1

Administration’s Fiscal Estimate for Proposed Local 1000 Agreement

(In Millions)

|

Rank and File Proposal |

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

|||||

|

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

|

|

General Salary Increases |

— |

— |

$104.0 |

$247.5 |

$189.5 |

$450.9 |

$298.6 |

$710.3 |

$298.6 |

$710.3 |

|

Monthly payment to employees enrolled in CalPERS health benefits |

— |

— |

102.4 |

244.7 |

102.4 |

244.7 |

102.4 |

244.7 |

102.4 |

244.7 |

|

Special Salary Adjustments |

— |

— |

35.1 |

125.1 |

35.1 |

125.1 |

35.1 |

125.1 |

35.1 |

125.1 |

|

Increasing minimum wage to $15 per hour |

— |

— |

13.1 |

24.9 |

14.3 |

27.1 |

14.3 |

27.1 |

14.3 |

27.1 |

|

Pay differentials |

$5.1 |

$9.0 |

11.7 |

26.7 |

11.7 |

26.7 |

11.7 |

26.7 |

11.7 |

26.7 |

|

Increased commute reimbursement |

1.8 |

4.4 |

2.5 |

5.9 |

2.5 |

5.9 |

2.5 |

5.9 |

2.5 |

5.9 |

|

Unit 3 health benefits |

— |

— |

0.5 |

0.5 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

2.6 |

2.7 |

|

Increased employee pension contribution |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

‑12.1 |

‑28.2 |

|

Totals |

$7.0 |

$13.4 |

$269.3 |

$675.3 |

$356.8 |

$881.8 |

$466.8 |

$1,142.1 |

$455.1 |

$1,114.3 |

Costs to Extend Provisions to Excluded Employees. The estimates above do not include any costs resulting from the state extending provisions of the agreement to managers, supervisors, and other employees who are excluded from the collective bargaining process but associated with the nine bargaining units represented by Local 1000. To avoid salary compaction between rank-and-file and managerial classifications, the administration typically provides excluded employees compensation increases comparable to what is provided to rank-and-file employees pursuant to an MOU. The administration estimates that extending the provisions to excluded employees could increase state costs by $5 million in 2019‑20 (about one-half from the General Fund). We estimate that extending the provisions of the agreement to excluded employees could increase annual state costs by a few hundred million dollars by 2022‑23.

Pay Increases

Most Recent Compensation Study From 2016. State law generally requires the administration to submit a compensation study to the Legislature six months before an agreement is scheduled to expire. These compensation studies can inform the Legislature to better understand how the state’s compensation for its employees compares with compensation provided by other employers for similar employees. The current agreement with Local 1000 will expire in January. Although the agreement will expire in fewer than six months, the administration indicates that a new compensation study will not be released until the fall. This is the second major tentative agreement in 2019 that the administration has submitted to the Legislature for consideration without providing a compensation study as is required by state law. Earlier in the year, the administration submitted to the Legislature an agreement with Bargaining Unit 6 (Corrections) without a new compensation study—the most recent Unit 6 compensation study was from 2013.

Without Compensation Study, Legislature Cannot Assess Need for Pay Increases. The most recent available compensation study uses data from 2014 and was released January 2016. Local 1000 compensation has changed significantly since 2014—for example, employees now contribute money to prefund retiree health benefits. Local 1000 represents a diverse range of state classifications—including custodial staff, accountants, nurses, and teachers. The 2016 report found numerous occupations represented by Local 1000 where the state compensates employees above market (for example, accountants, claims adjusters, civil engineering technicians, registered nurses, and librarians) and numerous occupations where the state compensated employees below market (for example, management analysts, computer systems analysts, software developers, legal secretaries, architectural and civil drafters, medical and clinical laboratory technicians, and nursing assistants). With the limited amount of time that we have to conduct our analysis, we cannot assess how the state’s relative compensation for these diverse classifications has changed since 2014 compared with other employers. However, it appears that a majority of the classifications that would receive an SSA under the proposed agreement were identified by the 2016 study to be in occupational groups where the state’s total compensation was above market.

Positions in Classifications That Would Receive SSAs Appear Not Especially Difficult to Fill. The ratio of vacant positions to authorized positions—a ratio referred to as the “vacancy rate”—is one indicator that can be used to help identify classifications that are difficult for the state to fill. It is important to note, however, that a vacancy rate should not be used in isolation to identify recruitment and retention issues (for example, a high vacancy rate may exist because a department just received position authority and is in the process of ramping up staffing levels). Across the nine bargaining units represented by Local 1000, the average vacancy rate in 2018 was 17 percent. Across the more than 140 classifications that would receive an SSA, the average vacancy rate in 2018 was about 14 percent. The vacancy rates for individual classifications that would receive an SSA ranged from 0 percent (meaning all authorized positions in that classification were full) to 100 percent (meaning that all authorized positions in that classification were vacant). The average vacancy rate among the affected classifications suggests that at least some of the classifications that would receive the SSAs may be less difficult to fill than the average classification represented by Local 1000.

Mandatory Overtime

Mandatory Overtime a Long Standing Issue. Hospitals and some other health care institutions must provide care to patients 24/7. The precise level of staffing necessary at any given time largely depends on patient acuity or needs and the number of patients at that time—for example, how many patients are on suicide watch and thus requiring a staff-to-patient ratio of one-to-one. When there are not enough nursing staff scheduled to adequately provide care to patients—either due to lack of resources, unexpected absences, scheduling error, emergency, or other causes—the state may require nursing staff to work overtime. Employees may receive very little notice that they will be required to work additional shifts. For example, Local 1000 informs us that an employee might learn at the end of his or her eight-hour shift that he or she will be required to work an additional eight-hour shift due to staffing shortages. Since 2001, state law has prohibited private sector medical providers from requiring nursing staff to work mandatory overtime. Past legislation aimed at establishing prohibitions or limitations on the state’s ability to use mandatory overtime have been vetoed by past governors under the premise that it is an issue best handled at the bargaining table. In 2016, the Little Hoover Commission released a report on the issue and found that the state relies heavily on overtime to meet staffing needs and that 20 percent of the overtime worked at that time was mandatory overtime. Although the Little Hoover Commission identified the state’s use of mandatory overtime as a problem, it found that excessive overtime—whether mandatory or voluntary—“is neither safe for patients nor staff, and should be significantly reduced.”

Long Shifts Increase Risk of Injury and Harm. At the Little Hoover Commission’s August 27, 2015 public hearing on the matter, state-employed nurses as well as psychiatric technicians described the risks associated with long hours. In particular, this testimony and the Little Hoover Commission’s 2016 report identified that long hours increase the likelihood of (1) employees being injured on the job—either as the result of accidental injury (most likely a back injury) or even by being assaulted by patients in a correctional setting, (2) nursing staff administering improper dosages or other accidental lapses in patient care, and (3) employees driving home drowsy—employees testified at the hearing of employees getting into car accidents after working long hours. A position paper issued by the American Nurses Association indicates that, although the Institute of Medicine recommends that nurses not exceed 12 hours of work in a 24-hour period and 60 total hours of work within seven days, research suggests that working more than 40 hours a week can adversely affect patient safety and the health of nurses. It likely is not good practice for nursing staff to work 16-hour days (regardless of whether 8 of those hours are due to voluntary or involuntary overtime).

Administration and Union Acknowledge Mandatory Overtime Is Ineffective, but Administration Continues Practice. Since at least 2016‑17—when the current agreement was ratified—the state has agreed that mandatory overtime is an ineffective staffing practice and has agreed that the use of mandatory overtime should be reduced. However, the state continues to rely on mandatory overtime. As Figure 2 shows, the use of mandatory overtime at DSH has consistently been above 30,000 hours in each of the past five fiscal years and even increased in the first year of the current agreement (2017‑18).

Figure 2

Hours of Mandatory Overtime Worked at State Hospitals

|

2014‑15 |

2015‑16 |

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

|

|

Atascadero |

4,140 |

5,141 |

5,835 |

1,735 |

1,259 |

|

Coalinga |

318 |

543 |

717 |

97 |

88 |

|

Metropolitan |

7,598 |

1,967 |

3,866 |

619 |

134 |

|

Napa |

22,379 |

21,009 |

23,721 |

34,230 |

26,410 |

|

Patton |

1,574 |

2,846 |

4,557 |

3,934 |

10,560 |

|

Totals |

36,008 |

31,505 |

38,696 |

40,614 |

38,451 |

At CalVet, not all of the eight facilities have used mandatory overtime in the past couple of years, but Yountville appears to rely heavily on the use of mandatory overtime. For example, in 2018‑19, the administration indicates that Yountville used 21,423 hours of mandatory overtime—three-fourths of the mandatory overtime used across all CalVet facilities. As Figure 3 shows, CDCR also continues to rely heavily on mandatory overtime. Based on the information that the three departments provided, it seems that mandatory overtime can vary significantly by institution from one year to the next. It appears to be something that may vary significantly depending on specific conditions at a particular facility at a particular time.

Figure 3

California Deparment of Corrections and Rehabilitation Use of Mandatory Overtime

Hours of Mandatory Overtime

|

2016‑17 |

2017‑18 |

2018‑19 |

|

|

California Health Care Facility |

6,127 |

11,998 |

31,581 |

|

Central California Women’s Facility |

14,191 |

11,504 |

13,796 |

|

California State Prison, Corcoran |

7,148 |

4,996 |

6,411 |

|

California Medical Facility |

6,194 |

16,375 |

5,572 |

|

California Men’s Colony |

6,072 |

5,127 |

5,176 |

|

Mule Creek State Prison |

4,643 |

6,873 |

4,765 |

|

California Institution for Women |

3,730 |

5,253 |

2,537 |

|

Salinas Valley State Prison |

2,983 |

4,666 |

2,525 |

|

Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility |

4,106 |

7,623 |

2,362 |

|

California Substance Abuse Treatment Facility and State Prison, Corcoran |

6,123 |

8,168 |

2,043 |

|

High Desert State Prison |

3,467 |

1,001 |

2,040 |

|

Pelican Bay State Prison |

1,758 |

1,598 |

1,962 |

|

Deuel Vocational Institution |

947 |

1,016 |

1,561 |

|

California State Prison, Sacramento |

2,438 |

1,566 |

1,487 |

|

Valley State Prison |

1,714 |

2,116 |

1,436 |

|

California Institution for Men |

2,180 |

9,619 |

1,337 |

|

Wasco State Prison |

1,355 |

1,911 |

1,148 |

|

Correctional Training Facility |

1,994 |

2,869 |

1,062 |

|

North Kern State Prison |

2,768 |

2,617 |

1,000 |

|

California State Prison, Centinela |

626 |

1,205 |

977 |

|

California State Prison, Solano |

3,090 |

1,279 |

925 |

|

San Quentin State Prison |

772 |

1,042 |

894 |

|

Sierra Conservation Center |

729 |

629 |

820 |

|

California State Prison, Los Angeles County |

1,660 |

2,889 |

647 |

|

Chuckawalla Valley State Prison |

703 |

652 |

606 |

|

California Correctional Center |

1,342 |

855 |

579 |

|

California Correctional Institution |

2,553 |

1,020 |

524 |

|

Folsom State Prison |

764 |

514 |

443 |

|

Ironwood State Prison |

765 |

670 |

429 |

|

Kern Valley State Prison |

848 |

606 |

390 |

|

Pleasant Valley State Prison |

1,228 |

1,087 |

351 |

|

California City Correctional Facility |

168 |

339 |

346 |

|

California Rehabilitation Center |

499 |

893 |

283 |

|

Calipatria State Prison |

519 |

388 |

267 |

|

Avenal State Prison |

511 |

168 |

207 |

|

Totals |

96,716 |

121,131 |

98,490 |

Reducing or Eliminating Mandatory Overtime Likely Will Require More Staff . . . The administration indicates that it has taken measures to reduce the use of mandatory overtime. Specifically, the administration indicates that departments have relied on registries, addressed scheduling errors, reassigned licensed staff from administration positions, and adjusted various licensing levels for one-to-one commitments (when a patient is on suicide watch). Despite these efforts, the use of mandatory overtime persists. Beyond the measures that the administration has already taken, it is not clear what actions the administration will take to reduce mandatory overtime. In some cases, approving additional staff may help reduce departments’ reliance on overtime. We would not be surprised if the Legislature receives a number of proposals along this line in January 2020. We note that increasing the number of employees only reduces overtime utilization if the additional positions are used to address existing workload. If new positions are used to address new workload, increasing the number of positions can actually increase the need for overtime to the extent that positions go unfilled and the department must use overtime to cover its new responsibilities.

. . . But Problem Seems More Complicated Than Simply Approving More Positions. However, the problem likely will not go away simply by approving increased position authority for these departments. Facilities that have challenges filing existing authorized positions likely also will have difficulty filling any new positions without other changes. The primary thing that likely affects facilities’ ability to recruit and retain nursing staff is the labor market—both in terms of the level of compensation the state provides relative to other employers in the market and in terms of the concentration of nursing staff in the region (the supply of labor). In addition to labor market considerations, there likely are other contributing factors that lead to some facilities relying more heavily than others on mandatory overtime.

Agreement in Context With Others Under Consideration

Twelve Agreements Now Before Legislature for Ratification. Over the past several weeks, we have analyzed proposed labor agreements between the state and 12 bargaining units. The Legislature will consider these agreements in the last remaining days of session. Combined, as shown in Figure 4, the administration estimates that these agreements will increase state costs in 2019‑20 by $128.1 million ($29.7 million from the General Fund). If ratified, the agreements will increase state annual costs by $1.5 billion ($517.8 million from the General Fund) by 2022‑23. After accounting for extending the provisions of the agreements to excluded employees, state costs likely would be several hundreds of millions of dollars higher by 2022‑23. On September 5, 2019, the administration submitted to the Legislature an agreement with Unit 2 (Attorneys). This analysis does not reflect the fiscal effects of the proposed Unit 2 agreement.

Figure 4

Administration’s Fiscal Estimates for Pending Labor Agreements a

(In Millions)

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

|||||

|

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

General Fund |

All Funds |

|

|

Local 1000 |

$7.0 |

$13.4 |

$269.3 |

$675.2 |

$356.8 |

$881.8 |

$466.8 |

$1,142.1 |

|

Unit 5 (Highway Patrol) |

— |

49.4 |

— |

107.1 |

— |

171.5 |

— |

256.5 |

|

Unit 7 (Protective Services and Public Safety) |

16.9 |

56.6 |

24.4 |

81.0 |

31.4 |

104.5 |

39.7 |

128.7 |

|

Unit 13 (Stationary Engineers) |

5.8 |

8.7 |

8.6 |

13.0 |

11.3 |

17.1 |

11.3 |

17.1 |

|

Totals |

$29.7 |

$128.1 |

$302.3 |

$876.3 |

$399.5 |

$1,174.9 |

$517.8 |

$1,544.4 |

|

aThe administration assumes that some of these costs will be paid from existing departmental resources and will not require additional appropriations from the Legislature. |

||||||||

Projected Costs Exceed Level of Funding Set Aside in Multiyear. Under Item 9901 of the budget act, the state set aside money to pay for new labor agreements. Specifically, the state set aside $100 million ($50 million General Fund) in 2019‑20, $500 million ($300 million General Fund) in 2020‑21, and $1 billion ($625 million General Fund) in 2021‑22 and beyond. Although the administration assumes that some of the costs shown in Figure 4 can be paid from existing budgetary resources and do not require a separate appropriation, the proposed agreements appear to increase ongoing annual state costs by more than what is assumed in the budget multiyear.

Common Themes Across Bargaining Units. Although each bargaining agreement reflects the unique circumstances of each bargaining unit, there are a few common themes that run through some or all of the agreements.

- Long Duration. The agreements all would be in effect for at least three years. Agreements with terms longer than two years are more likely to limit legislative oversight and flexibility to respond to budget problems.

- Increase Pay. The agreements all would increase pay for most—if not all—of the employees represented by the bargaining unit. The base pay increases are in the range of 3 percent each year and the agreements provide additional pay for specified classifications or purposes.

- Maintain State’s Retirement Benefit Funding Policies. The agreements maintain the state’s policy that the state and its employees generally share equally—as a percentage of pay—the normal cost to prefund pension benefits and retiree health benefits.

- Geographic Pay. The Local 1000 agreement and the Unit 13 agreement each contain some form of pay differential for employees who work in specified high cost regions of the state. Recent compensation studies produced by CalHR have indicated that the state’s relative competitiveness in the labor market can vary significantly across the state—with state compensation typically lagging in high cost regions. Rather than approving geographic differentials in a piecemeal approach, the Legislature could consider a more broad change to state employee compensation policy to take into consideration regional differences in cost of living—for example, adopting regional salary schedules similar to the federal government’s locality adjustments to the general salary schedule.

- Units 5 and 7 Agreements Establish New Role for Director of Finance. The agreements with Units 5 and 7 create a new role for the Director of Finance whereby the Director can determine whether there are sufficient revenues for certain provisions to go into effect. If the Director determines there are not sufficient revenues, the Director can reopen the agreement.

Motor Vehicle Account (MVA)

MVA Is One of Hundreds of Special Funds. The state’s primary operating fund is the General Fund. In addition to the General Fund, the state has hundreds of special funds that serve as the operational funding source for programs with specific purposes. The primary funding source for special funds often are fees for service. Some special funds operate at a surplus while others have significant challenges due to some combination of declining revenues and increasing expenditures. For many departments, the largest category of expenditure is related to employee compensation. For departments funded by a challenged special fund, growth in employee compensation costs beyond what currently is projected can further weaken the special fund’s condition.

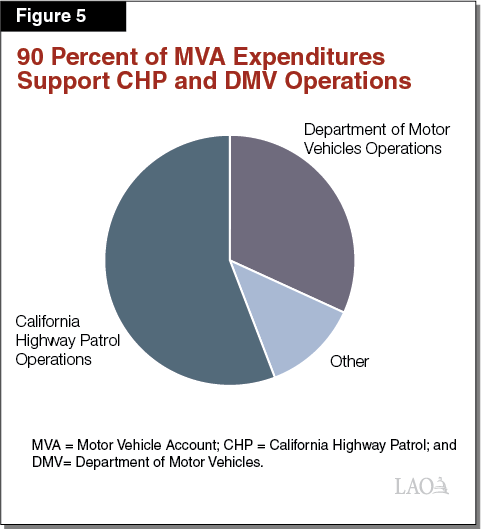

Most MVA Expenditures Pay for California Highway Patrol (CHP) and Department of Motor Vehicle (DMV) Operations. In 2019‑20, the MVA is expected to have $4.2 billion in expenditures. As Figure 5 shows, CHP and DMV operations account for 90 percent of the MVA’s expenditures. Most of the two departments’ expenditures from the MVA are expected to pay for employee compensation. Specifically, the CHP expects to spend about $1.8 billion MVA funds on employee compensation and DMV expects to spend about $890 million MVA funds on employee compensation.

MVA Has Had Challenges in Recent Years. Over the last several years, the MVA has periodically faced operational shortfalls—meaning planned expenditures exceeded combined revenues and transfers. For example, the MVA faced an operational shortfall in 2015‑16 of about $300 million, which was addressed through the one-time repayment of $480 million in loans that were previously made from the MVA to the General Fund. In 2016‑17, the MVA faced an operational shortfall of roughly the same magnitude and possible insolvency in 2017‑18. In order to address this shortfall and help maintain the solvency of the MVA, the Legislature increased revenues into the account by increasing the base vehicle registration fee by $10 in 2016 and indexing it to the consumer price index.

Legislature Took Recent Action to Prevent MVA From Becoming Insolvent. As we discussed in our February 2019 analysis, the MVA began the year facing a 2018‑19 operational shortfall of almost $400 million. Without corrective action, the MVA likely would have again experienced an operational shortfall in 2019‑20 and potentially have become insolvent in the future. In order to help address the MVA’s solvency, as well as increased MVA expenditures in the current year (such as a net increase of $242 million for DMV to process federally compliant driver licenses and identification cards), the 2019‑20 budget includes various actions intended to benefit the MVA in the near term (such as suspending a transfer of revenues from the MVA to the General Fund and delaying facility projects). After these corrective actions, the administration projects that the fund will have a reserve of about $100 million in 2022‑23 (this projection also assumes that additional future spending—about $50 million—proposed by the Governor is approved).

MVA Might Be Less Stable Than Assumed . . . The administration’s projected MVA fund balance assumes that (1) highway patrol officers receive a 3 percent salary increase each year and (2) DMV’s payroll costs grow 2 percent each year. These assumptions probably do not accurately predict costs under current law. For example, in estimating the costs of the Unit 5 agreement, the administration assumes that the statutory formula-driven pay increases will exceed 3 percent each year. In addition, the 2 percent growth at DMV may underestimate salary growth and growth in CalPERS pension contributions. It is possible that—under current law—the MVA already is on a path towards an operational shortfall within the next few years.

. . . And Likely Would Be Further Weakened by Labor Agreements. Any growth in CHP or DMV compensation above current assumptions could weaken the MVA fund condition. Based on the administration’s estimates of the agreements with Local 1000, Unit 5 (Highway Patrol), and Unit 7 (Protective Services and Public Safety)—together representing virtually all rank-and-file CHP and DMV employees—it seems that costs would grow faster under the terms of the agreement than the administration currently assumes, meaning that the Legislature likely will need to take additional actions to keep the MVA solvent. Specifically, comparing the compensation growth the administration assumes with the compensation growth provided by the proposed agreements and expected growth in pension contributions, we estimate that MVA costs could be between $100 million and $200 million above current estimates by 2022‑23. If correct, this means the MVA likely will have an operating shortfall sometime before 2022‑23. The administration indicates that it is monitoring the fund and will explore options—if necessary—to keep the fund’s reserve at $100 million. In addition, the administration indicates that it will provide the Legislature an updated fund condition that incorporates the proposed labor agreements in January with the Governor’s Budget.