LAO Contact

October 5, 2020

The 2020‑21 Budget

Overview of the California Spending Plan

(Final Version)

Each year, our office publishes the California Spending Plan to summarize the annual state budget. This publication provides an overview of the 2020‑21 Budget Act, provides a short history of the notable events in the budget process, and then highlights major features of the budget approved by the Legislature and signed by the Governor. All figures in this publication reflect the administration’s estimates of actions taken through June 30, 2020, but we have updated the narrative to reflect actions taken later in the legislative session. In addition to this publication, we have released a series of issue‑specific posts providing more detail on various programmatic aspects of the budget.

Budget Overview

The $54.3 Billion Budget Problem

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‑19) pandemic has had far‑reaching negative impacts on the state economy, which have direct and indirect implications for the state budget. The final spending plan reflects an estimated $54.3 billion General Fund budget problem for the 2020‑21 budget. This budget problem was estimated by the administration at the time of May Revision (as we discuss further in the “Evolution of the Budget” section of this report) and is the net result of a number of factors, including (most notably):

- Lower Revenues. The most significant cause of the state’s budget problem is a substantial decline in revenues. Largely as a result of a severe decline in economic activity, the administration’s estimates for revenues in both 2019‑20 and, most notably, 2020‑21, declined substantially between January and May. Overall, the spending plan anticipates revenues will be lower across the budget window by $42 billion.

- Higher Caseload‑Related Spending. Another major driver of the state’s budget problem is higher caseload‑related costs across the state’s safety net programs, including: Medi‑Cal, California Work Opportunity and Responsibility to Kids (CalWORKs), and CalFresh. In particular, the budget assumes a 9.2 percent year‑over‑year increase in Medi‑Cal enrollees, a 51.1 percent increase in CalFresh participation, and a 42.4 percent increase in CalWORKs participating families.

Revenues

Figure 1 displays the administration’s revenue projections as incorporated into the June 2020 budget package. The budget package assumes General Fund revenues and transfers will be $137.7 billion in 2020‑21, which is essentially flat over the revised 2019‑20 estimates. This is the result of two significant and offsetting factors. First, tax revenue from the state’s three largest sources is projected to decline by 15 percent relative to 2019‑20. These revenue declines would have been even larger absent two conditions. One, tax credit and deduction policy changes are expected to result in additional revenues of $4.4 billion, which we discuss later in this report. Two, other revenues are significantly larger because the budget scores federal funding received for disaster assistance (in particular related to direct COVID‑19 spending) as other revenues.

Figure 1

General Fund Revenue Estimates

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Revised |

Enacted 2020‑21 |

Change From 2019‑20 |

|||

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

Amount |

Percent |

||

|

Personal income tax |

$99,189 |

$95,566 |

$77,567 |

‑$17,999 |

‑19% |

|

Sales and use tax |

26,150 |

24,941 |

20,583 |

‑4,358 |

‑17 |

|

Corporation tax |

14,075 |

13,870 |

16,534 |

2,665 |

19 |

|

Subtotals |

($139,414) |

($134,377) |

($114,684) |

(‑$19,693) |

(‑15%) |

|

Insurance tax |

$2,727 |

$3,052 |

$2,986 |

‑$66 |

‑2% |

|

Other revenues |

2,344 |

4,199 |

7,704 |

3,505 |

83 |

|

Transfer to BSA |

‑3,189 |

‑2,120 |

— |

— |

— |

|

Transfer from BSA |

— |

— |

7,806 |

— |

— |

|

Other transfers and loans |

‑1,237 |

‑1,883 |

4,539 |

6,422 |

‑341 |

|

Totals, Revenues, and Transfers |

$140,060 |

$137,625 |

$137,719 |

$94 |

— |

|

Note: Reflects administration estimates of budgetary actions taken through July 1, 2020. |

|||||

|

BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||||

Second, offsetting the decline in tax revenue, transfers and other revenues will increase substantially between 2019‑20 and 2020‑21. This occurs as the spending plan uses reserve transfers and loans from special funds to address the budget problem.

Total State and Federal Spending

Figure 2 displays the administration’s June 2020 estimates of total state and federal spending in the 2020‑21 budget package. As the figure shows, the spending plan assumes total state spending of $196 billion (excluding federal and bond funds), a decrease of 4 percent over revised totals for 2019‑20. General Fund spending in 2020‑21 is $133.9 billion—a decrease of $13 billion, or 9 percent, over the revised 2019‑20 level.

Figure 2

Total State and Federal Expenditures

(Dollars in Millions)

|

Revised |

Enacted 2020‑21 |

Change From 2019‑20 |

|||

|

2018‑19 |

2019‑20 |

Amount |

Percent |

||

|

General Fund |

$140,387 |

$146,933 |

$133,900 |

‑$13,033 |

‑9% |

|

Special funds |

57,152 |

57,874 |

62,115 |

4,241 |

7 |

|

Budget Totals |

$197,539 |

$204,807 |

$196,015 |

‑$8,792 |

‑4% |

|

Bond funds |

$5,704 |

$7,187 |

$6,059 |

‑$1,129 |

‑16% |

|

Federal funds |

97,202 |

125,714 |

159,878 |

34,164 |

27 |

|

Note: Reflects administration estimates of budgetary actions taken through July 1, 2020. |

|||||

Federal funding in 2020‑21 is expected to be $159.9 billion—an increase of $34.2 billion over the revised 2019‑20 level. Increased federal funding is the result of two main factors: (1) enhanced federal reimbursements for the state’s Medicaid programs and (2) the state’s receipt of $9.5 billion in Coronavirus Relief Funds (CRF) to respond to the costs of the public health emergency. (The state also is anticipated to receive billions of dollars in reimbursements from the Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], but these are scored as revenues rather than federal expenditures.)

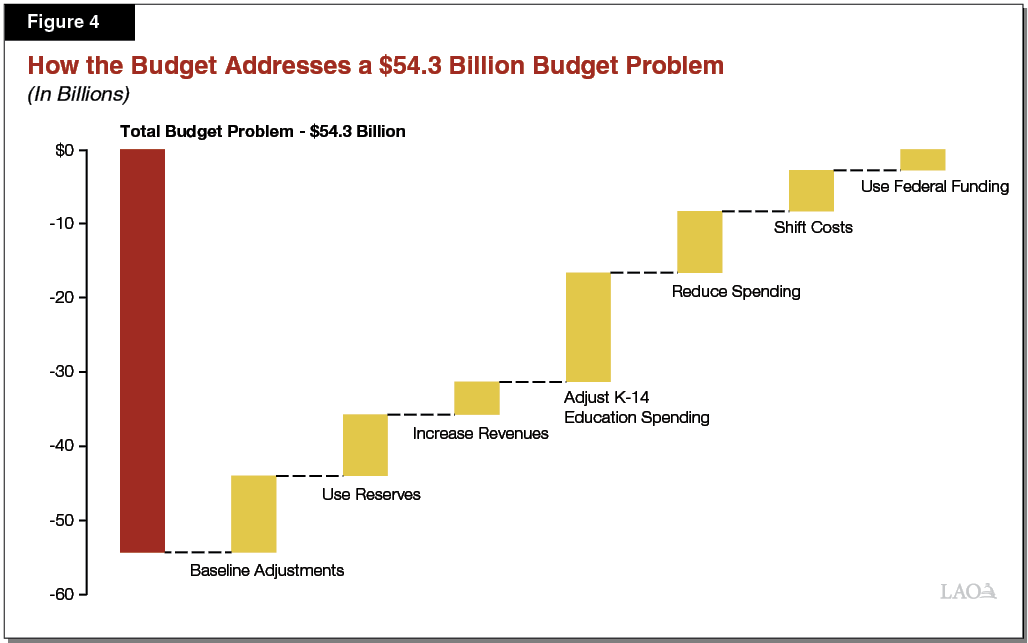

Solutions Adopted During the Budget Process

This section describes the solutions adopted in the 2020‑21 Budget Act to address the estimated $54.3 billion budget problem identified by the administration during the May Revision.

Budget Solutions Adopted to Address a $54.3 Billion Budget Deficit. Figures 3 and 4 summarize the budget solutions adopted in the 2020‑21 Budget Act. They are:

- Make Baseline Adjustments and Assumptions (19 percent). First, the spending plan uses $10.3 billion in adjustments and assumptions that do not involve choices about changes to current law. For example, compared to the May Revision, the spending plan assumes revenues will be higher and CalWORKS caseload will be lower, resulting in improvements to the budget bottom line.

- Use Reserves (15 percent). The budget package authorizes $8.3 billion in reserve withdrawals to cover the state’s General Fund budget problem. We describe the state’s reserve situation in more detail in the next section on the condition of the General Fund.

- Increase Revenues (8 percent). The budget package includes two actions that the administration estimates will increase tax revenues by an estimated $4.4 billion in 2020‑21. First, the budget temporarily suspends net operating loss (NOL) deductions, preventing corporations with net income over $1 million from using NOLs in 2020, 2021, and 2022. Second, the budget limits businesses from claiming more than $5 million in tax credits (excluding the low‑income housing tax credit) in 2020, 2021, and 2022.

- Adjust K‑14 Education Spending (27 percent). The budget package provides state spending at the constitutional minimum level for schools, largely achieved by providing $12.5 billion in payment deferrals and $2.2 billion in other adjustments. (Deferrals allow the state to reduce the budgeted spending level on schools while allowing schools to continue to operate a larger program by borrowing or using cash reserves.) We describe the state’s overall spending on K‑14 education in the “Major Features” section of this report.

- Reduce Spending (15 percent). There are $8.3 billion in spending reductions across the budget. Many of these spending reductions—such as reductions to state employee pay and lower spending on higher education and the judicial branch—are subject to the federal trigger legislation. This means the reductions will be cancelled on October 15, 2020 if more federal aid is forthcoming to the state. (We discuss the federal trigger legislation in more detail below.) This section also includes the withdrawal of some of the Governor’s January proposals. Although we would typically display these types of changes as “baseline adjustments,” we did not have sufficient information to do so.

- Shift Costs and Borrowing (10 Percent). The budget takes a number of actions that shift costs, either from the General Fund to other funds or from the current year to future years. Together, these actions address $5.5 billion of the budget problem. We discuss these actions further in the “Major Features” section of this report.

- Use Federal Funds (5 percent). In a number of places the spending plan uses federal funds to offset state spending, which partially addresses the budget problem. For example, the spending plan allocates $2.7 billion to state programs, such as public safety and public health, from the federal CRF. We discuss how the spending plan allocates the entire $9.5 billion in CRF monies in the “Major Features” section of this report.

Figure 3

Actions Taken to Address a $54.3 Billion Budget Problem in the 2020‑21 Budget Package

(In Billions)

|

Subject to Trigger |

Not Subject to Trigger |

Total |

|

|

Make Baseline Adjustmentsa |

|||

|

Account for higher federal Medicaid funding |

— |

$5.3 |

$5.3 |

|

Assume lower CalWORKs caseload |

— |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Assume higher revenues |

— |

1.0 |

1.0 |

|

Assume receipt of additional federal funds |

— |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Use Reserves |

|||

|

Make BSA withdrawal |

— |

7.8 |

7.8 |

|

Make Safety Net Reserve withdrawal |

— |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

Increase Revenues |

|||

|

Suspend net operating losses |

— |

1.8 |

1.8 |

|

Limit business incentive tax credits |

— |

2.0 |

2.0 |

|

Interaction between the two above items |

— |

0.6 |

0.6 |

|

Make Deferrals and Adjustments to K‑14 Education Spending |

|||

|

Defer education‑related spending |

$6.6 |

5.9 |

12.5 |

|

Other adjustments |

2.2 |

2.2 |

|

|

Reduce Spending |

|||

|

Reduce spendinga |

3.6 |

4.7 |

8.3 |

|

Shift Costs |

|||

|

Make special fund loans |

0.9 |

2.1 |

3.0 |

|

Shift pension costs |

— |

1.7 |

1.7 |

|

Convert capital financing to LRBs |

— |

0.7 |

0.7 |

|

Make special fund transfers |

— |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Use Federal Funding |

|||

|

Allocate Coronavirus Relief Fund to state |

— |

2.7 |

2.7 |

|

Use CCDBG funds |

— |

0.1 |

0.1 |

|

Total |

$11.1 |

$43.2 |

$54.3 |

|

aSome solutions displayed in the “Reduce Spending” section of this table should be included as baseline adjustments because they are withdrawals of January proposals. We did not have sufficient information from the administration to display these items separately in this table. |

|||

|

BSA = Budget Stabilization Account; LRBs = lease revenue bonds; and CCDBG = Child Care and Development Block Grant. |

|||

$11 Billion in Spending Reductions and Other Changes Restored if Federal Funds Are Forthcoming. The budget makes about $11 billion in spending reductions, K‑14 deferrals, and special fund loans subject to federal “trigger” language in Control Section 8.28 (see Figure 5 ). Under this language, if the federal government passes legislation by October 15, 2020 providing at least $14 billion in funding to the state, all of the amounts subject to the trigger would be restored. If the federal government provides less than $14 billion, the restorations would be made proportional to their share of the total. (The budget also assumes the state will receive $2 billion in new federal funding that could be used flexibly, which is displayed as baseline adjustment above.) As of this writing (September 30, 2020), the federal government had not passed such legislation.

Figure 5

Spending Reductions and Deferrals “Triggered Off” if Federal Funds Are Forthcoming

(In Billions)

|

Education‑Related Deferrals |

$6.55 |

|

Spending Reductions |

|

|

Employee compensation reduction |

1.89 |

|

Higher education reductions |

0.97 |

|

Special fund loansa |

0.94 |

|

Realignment backfill |

0.25 |

|

Infill infrastructure grant program reversion |

0.20 |

|

Judicial branch reduction |

0.15 |

|

Golden State Teacher Grant Program reduction |

0.09 |

|

Child support agency funding reversion |

0.05 |

|

Moderate‑income housing reversion |

0.05 |

|

Total, Spending Reductions |

$4.58 |

|

Total |

$11.14 |

|

aBorrowing from special fund loans related to employee compensation savings. Note: Numbers may not total due to rounding. |

|

Some Spending Is Subject to Potential Suspension in 2021‑22. Similar to action taken in 2019‑20, the spending plan makes some spending subject to suspension in 2021‑22. In these cases, statute directs the Department of Finance (DOF) to calculate whether General Fund revenues will exceed General Fund expenditures—without suspensions—in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. If DOF determines revenues will exceed expenditures, then the programs’ ongoing spending amounts will continue and not be suspended. Otherwise, the expenditures are automatically suspended. In most cases, suspensions would occur halfway through the fiscal year (on December 31, 2021). One exception is the suspension of the use of Proposition 56 revenues for Medi‑Cal provider payment increases. Under the spending plan, this suspension would take effect at the beginning of the fiscal year (on July 1, 2021). Figure 6 shows the estimated General Fund savings in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23 if the suspensions are operative.

Figure 6

Programmatic Funding Subject to Potential Suspension

(In Millions)

|

Program |

Funding Suspension |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

|

Medi‑Cal |

Use of Proposition 56 revenues for provider payment increases |

$768.9 |

$799.5 |

|

IHSS |

Continued restoration of 7 percent service hour reduction |

229.3 |

500.7 |

|

DDS/DOR |

Supplemental provider payment increases |

139.1 |

299.1 |

|

Medi‑Cal |

Extension of Medi‑Cal coverage for postpartum mental health |

17.8 |

35.6 |

|

Medi‑Cal |

Restoration of optional benefits |

17.6 |

35.2 |

|

DDS |

Nonenforcement of uniform holiday schedule policy |

17.5 |

35.0 |

|

Child welfare |

Funding for Family Urgent Response System |

15.0 |

30.0 |

|

DDS |

Additional supplemental provider payment increases |

10.8 |

23.6 |

|

Senior nutrition |

Augmentation for Senior Nutrition Program |

8.8 |

17.5 |

|

Child welfare |

Emergency Child Care Bridge Program supplement |

5.0 |

10.0 |

|

UC and CSU |

Student financial aid during the summer |

5.0 |

10.0 |

|

Child welfare |

Public health nursing early intervention pilot program in Los Angeles County |

4.1 |

8.3 |

|

Senior nutrition |

State funding for Aging and Disability Connection program |

2.5 |

5.0 |

|

Child welfare |

Foster Family Agency social worker rate increase |

3.2 |

6.5 |

|

HCD |

All Transitional Housing Program grants to counties for former foster youth |

4.0 |

8.0 |

|

Medi‑Cal |

Expansion of screening and intervention to drugs other than alcohol |

0.2 |

0.4 |

|

Total General Fund Savings |

$1,248.8 |

$1,824.4 |

|

|

IHSS = In‑Home Supportive Services; DDS = Department of Developmental Services; DOR = Department of Rehabilitation; and HCD = Housing and Community Development. |

|||

The Condition of the General Fund

Figure 7 summarizes the condition of the General Fund under the revenue and spending assumptions in the June 2020 budget package, as estimated by DOF.

State Makes First‑Ever Withdrawal From BSA Under Rules of Proposition 2. The Budget Stabilization Account (BSA) is governed by constitutional rules under Proposition 2, which was enacted by voters in 2014. Proposition 2 limits when—and how much—the state can withdraw from the BSA in any given year. The 2020‑21 budget makes a withdrawal of $7.8 billion from the BSA, the first‑ever withdrawal under the rules of Proposition 2. The withdrawal is made pursuant to the Governor’s disaster declaration in response to the COVID‑19 public health emergency and proclamation of a budget emergency on June 25, 2020. In addition, the spending plan transfers $450 million from the Safety Net Reserve.

Figure 7

General Fund Condition Summary

(In Millions)

|

2019‑20 |

2020‑21 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$11,280 |

$1,972 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

137,625 |

137,719 |

|

Expenditures |

146,933 |

133,900 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$1,972 |

$5,791 |

|

Encumbrances |

$3,175 |

$3,175 |

|

SFEU balance |

‑1,203 |

2,616 |

|

Reserves |

||

|

BSA balance |

$16,116 |

$8,310 |

|

SFEU balancea |

‑1,203 |

2,616 |

|

Safety net reserve |

900 |

450 |

|

Totals |

— |

$11,376 |

|

aIncludes $716 million in COVID‑19 reserve. Note: Reflects administration estimates of budgetary actions taken through July 1, 2020. SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties ; BSA = Budget Stabilization Account ; and COVID‑19 = coronavirus disease 2019. |

||

2020‑21 Would End With $11.4 Billion in Reserves. Under the spending plan assumptions and estimates, 2020‑21 would end with $11.4 billion in reserves. This includes $8.3 billion in the BSA, $2.6 billion in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU), and $450 million in the Safety Net Reserve. The balance of the SFEU includes $716 million designated for COVID‑19 contingency. Under existing law, the Governor can transfer funds from the SFEU to the Disaster Response Emergency Operations Account (DREOA, a subaccount within the SFEU) with notification to the Legislature. Monies transferred into DREOA are continuously appropriated for disaster response and recovery operation costs incurred by state agencies during a state of emergency.

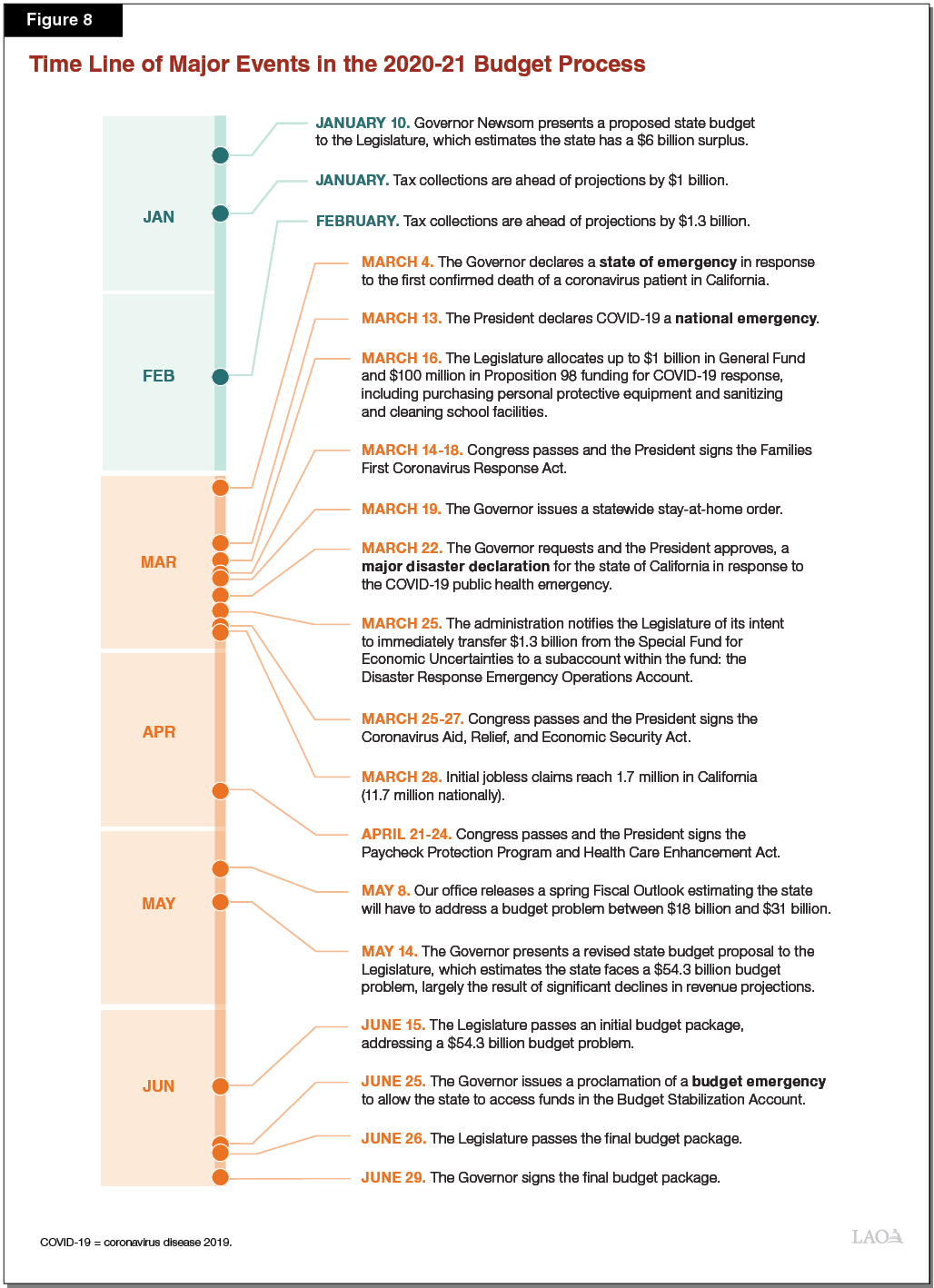

Evolution of the Budget

Governor’s January Budget Anticipated the State Would Have a Surplus of $6 Billion. Governor Newsom presented his proposed state budget to the Legislature on January 10, 2020, as Figure 8 shows. At the time, the administration expected revenues for 2019‑20 to continue to exceed expectations from the 2019‑20 Budget Act. With continued expected revenue growth, the administration anticipated a surplus of about $6 billion for 2020‑21. The Governor proposed allocating that surplus to a variety of purposes, two of the largest of which were homelessness and re‑envisioning Medi‑Cal.

COVID‑19 Emergency Resulted in Rapidly Evolving Public Health and Economic Situation. In March, the state’s public health and economic situations began to change dramatically. On March 4, 2020, the Governor declared a state of emergency in response to the first confirmed death of a coronavirus patient in California. On March 19, the Governor issued an executive order requiring Californians to shelter in place statewide. A few days later, the Governor requested and the President approved a major disaster declaration for the state of California in response to the COVID‑19 public health emergency. Meanwhile, in March, California experienced an unprecedented rise in unemployment. For example, between March 22 and 28, California processed more than 1 million initial claims for regular unemployment insurance, surpassing the record high prior to COVID‑19 by nearly ten times.

State Began Incurring Significant Direct Costs to Respond to COVID‑19. Before beginning a recess in mid‑March, the Legislature passed Chapter 2 of 2020 (SB 89, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) and Chapter 3 of 2020 (SB 117, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review), which authorized the administration to spend up to $1 billion for COVID‑19 response and provided funding for schools to purchase equipment and clean facilities. In addition, the administration used its authority under DREOA in March to make additional COVID‑19‑related expenditures.

Congress Passed Legislation to Address COVID‑19. In March and April, the federal government passed legislation directing funding to states, local governments, and private entities in response to the COVID‑19 emergency. This legislation included: the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Act; the Families First Coronavirus Response Act; the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act; and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act. Among many other changes, these pieces of legislation provided additional funding for state and local governments to respond to COVID‑19; increased the federal share of costs for state Medicaid programs; provided financial assistance to small businesses; increased unemployment insurance benefits; and provided direct, broad‑based cash assistance to most individuals. In addition, federal emergency declarations authorized FEMA to provide additional funding to states and local governments to reimburse them for certain COVID‑19‑related costs.

In the May Revision, Administration Estimated State Faced $54.3 Billion Budget Problem. Shortly before the May Revision was released, our office published a Spring Fiscal Outlook estimating the state faced a budget problem likely ranging between $18 billion and $31 billion depending on the economic trajectory of the next year. On May 14, 2020, Governor Newsom presented a revised state budget proposal to the Legislature, which estimated the state faced a $54.3 billion budget problem. Although the administration’s revenue estimates were similar to those at the higher end of our predicted range of budget problems, the administration made other assumptions that resulted in a larger budget problem. (We explained the difference between our estimates in The 2020‑21 Budget: Initial Comments on the May Revision.) The Governor’s May Revision included a number of proposed solutions across a wide range of areas to solve the budget problem.

Initial Budget Package Passed on June 15, 2020. The Legislature passed an initial budget on June 15, 2020. A key feature of the initial budget package is that it assumed $14 billion in federal funding would be forthcoming, reducing the need for spending reductions and other actions to balance the budget. The initial budget package also would have reinstated two General Fund payment deferrals, including a fourth quarter payment deferral to California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) and the state employee payroll deferral.

Final Budget Package Signed on June 29, 2020. The Legislature passed a final budget package on June 26, 2020. The final budget package assumed that $2 billion in federal funds would be forthcoming and took the Governor’s approach in the May Revision to make other spending reductions contingent on other federal money. In addition, relative to the June 15 initial package, the final package made several changes, including increasing school deferrals by $3.5 billion (assuming no federal money is forthcoming), increasing revenue assumptions by more than $1 billion, and eliminating the plan to reinstate General Fund payment deferrals. The Governor signed the 2020‑21 Budget Act and related budget legislation on June 29, 2020. The Governor made one line item veto. Figure 9 lists the budget and budget‑related legislation passed as of July 1, 2020.

Figure 9

Budget‑Related Legislation

|

Bill Number |

Chapter |

Subject |

|

Legislation Signed Before July 1, 2020 |

||

|

SB 74 |

6 |

2020‑21 Budget Act |

|

AB 89 |

7 |

Amendments to the 2020‑21 Budget Act |

|

AB 75 |

9 |

Amendments to the 2019‑20 Budget Act |

|

AB 76 |

5 |

Proposition 98 2019‑20 deferrals and settle‑up payments |

|

AB 78 |

10 |

Infrastructure and economic development bank |

|

AB 79 |

11 |

Human services |

|

AB 80 |

12 |

Health omnibus |

|

AB 81 |

13 |

Health funding |

|

AB 82 |

14 |

State government |

|

AB 83 |

15 |

Housing |

|

AB 84 |

16 |

Public employment and retirement |

|

AB 85 |

8 |

State taxes and charges |

|

AB 90 |

17 |

Transportation |

|

AB 92 |

18 |

Public resources |

|

AB 93 |

19 |

Earned income tax credit |

|

AB 100 |

20 |

State government |

|

AB 102 |

21 |

Retirement savings |

|

AB 103 |

22 |

Unemployment compensation benefits |

|

SB 98 |

24 |

Schools and child care |

|

SB 116 |

25 |

Higher education |

|

Legislation Signed After July 1, 2020 |

||

|

SB 115 |

40 |

Amendments to the 2019‑20 and 2020‑21 Budget Acts |

|

AB 107 |

264 |

General government |

|

AB 1867 |

45 |

Small employer family leave mediation |

|

AB 1869 |

92 |

Criminal fees |

|

AB 1872 |

93 |

Cannabis |

|

AB 1876 |

87 |

Earned Income Tax Credit |

|

AB 1885 |

94 |

Debtor exemptions: homestead exemption |

|

SB 118 |

29 |

Public safety |

|

SB 119 |

30 |

State employment: state bargaining units |

|

SB 820 |

110 |

Education finance |

|

SB 823 |

337 |

Juvenile justice realignment |

|

Note: This figure includes budget bill and trailer bills identified in Section 39.00 of the 2020‑21 Budget Act that were enacted into law. |

||

Major Features of the 2020‑21 Spending Plan

Education

Early Education

Removes Unused Early Education Funds. The budget plan makes $161 million in ongoing reductions to State Preschool ($130 million Proposition 98 General Fund and $31 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund). Most of these funds are prior‑year augmentations that were never awarded to State Preschool providers. To achieve additional savings, the budget plan also rescinds unspent funds from initiatives included in the 2019‑20 budget. This includes $263 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund intended to help child care providers construct or renovate facilities and $195 million ($150 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund and $45 million federal funds) to improve and expand child care and preschool workforce training. (The budget redirects the bulk of the federal funds to partially backfill General Fund costs for Stage 3 child care in 2020‑21.)

Allocates Additional Federal Funds. Chapter 24 of 2020 (SB 98, Committee on Budget and Fiscal Review) allocated $350 million one time federal funds provided in the CARES Act. Funds will be used to (1) cover 2019 20 expenses related to COVID 19, (2) reimburse child care providers for authorized hours of care instead of child care hours used, (3) provide stipends for voucher providers, (4) provide an additional 14 paid non‑operation days for voucher providers, and (5) extend temporary voucher child care for an additional 90 days. The budget also provides a $47 million ongoing federal fund increase for alternative payment slots. The additional slots are to be prioritized to provide care for children previously served with temporary voucher slots.

K‑14 Education

Reduces School and Community College Funding to Reflect Lower Minimum Requirement. Proposition 98 (1988) established a minimum annual funding requirement for schools and community colleges. This minimum requirement depends upon various formulas that adjust for changes in state General Fund revenue and other factors. Due to the significant drop in state revenues, the minimum requirement is down $3.4 billion in 2019‑20 from the June 2019 estimates. In 2020‑21, the minimum requirement drops by an additional $6.8 billion (8.7 percent) from the revised 2019‑20 level (Figure 10). The budget plan funds schools and community colleges at the lower required levels. It implements the reductions, as well as various other changes, primarily by deferring $12.5 billion in payments to districts. (When the state defers payments from one fiscal year to the next, the state can reduce spending while allowing school districts to maintain programs by borrowing or using cash reserves.) If the state receives additional federal funding, up to $6.6 billion would instead be paid on the regular schedule.

Figure 10

Proposition 98 Funding by Segment and Source

(Dollars in Millions)

|

2018‑19 Final |

2019‑20 Revised |

2020‑21 Enacted |

Change From 2019‑20 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Funding by Segment |

|||||

|

K‑12 Education |

$69,311 |

$68,568 |

$62,525 |

‑$6,043 |

‑8.8% |

|

California Community Colleges |

9,211 |

9,109 |

8,365 |

‑745 |

‑8.2 |

|

Totals |

$78,522 |

$77,678 |

$70,890 |

‑$6,788 |

‑8.7% |

|

Funding by Source |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$54,746 |

$52,656 |

$45,066 |

‑$7,590 |

‑14.4% |

|

Local property tax |

23,776 |

25,022 |

25,824 |

802 |

3.2 |

|

Note: Amounts reflect June 2020 enacted budget levels, assuming the state does not receive additional federal funding. |

|||||

Creates Supplemental Obligation to Increase Funding in Future Years. This obligation has two parts. First, it requires the state to make temporary payments on top of the Proposition 98 requirement beginning in 2021‑22. Each payment will equal 1.5 percent of annual General Fund revenue and can be allocated for any school or community college purpose. These payments will continue until the state has paid $12.4 billion—the amount of funding schools and community colleges could have received under Proposition 98 if state revenues had continued to grow. Second, the obligation requires the state to increase the minimum share of General Fund revenue allocated to schools and community colleges from 38 percent to 40 percent on an ongoing basis. This increase is set to phase in over the 2022‑23 and 2023‑24 fiscal years.

Repurposes Prior Pension Payment to Reduce District Costs Over the Next Two Years. The 2019‑20 budget plan included a $2.3 billion supplemental pension payment on behalf of schools and community colleges. Of this $2.3 billion, $1.6 billion was for the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) and $660 million was for CalPERS. At the time, the state estimated that the supplemental payment could reduce district pension costs by roughly 0.3 percent of annual pay over the next few decades. The 2020‑21 budget plan repurposes this payment to reduce pension costs by a larger amount over the next two years. Specifically, districts will receive cost savings of approximately 2 percent of pay in 2020‑21 and 2021‑22 (about $1.15 billion per year), but will not experience savings over the following decades.

Universities

Enacted Budget Notably Reduces General Fund Support for the Universities. Ongoing General Fund spending decreases by a net of $251 million (5.8 percent) for the California State University (CSU) and $259 million (7 percent) for the University of California (UC) from 2019‑20 to 2020‑21. General Fund reductions to the UC’s and CSU’s base operations are partially offset by targeted ongoing augmentations. Targeted augmentations include covering higher pension costs at CSU and expanding certain medical education programs at UC. The budget does not set enrollment targets for either CSU or UC, and it assumes both segments hold resident tuition flat in 2020‑21. After accounting for tuition and other core revenue, total ongoing core support decreases 3.3 percent at CSU and 2.1 percent at UC.

If State Receives Additional Federal Relief Funding, Support for CSU and UC Would Notably Increase. The universities are included in the state’s contingency plan as set forth in Section 8.28 of the 2020‑21 Budget Act. If the state receives at least $14 billion in additional federal relief funding by October 15, 2020, the budget allocates $498 million of this funding to CSU and $472 million to UC. These amounts would not only eliminate base reductions for the universities but provide each segment with the equivalent of a 5 percent General Fund base increase. (At UC, this base increase applies only to its core campus operations, not its centralized systemwide operations.) Total ongoing core support would increase 2.6 percent at CSU and 3 percent at UC. (If the state receives more than $2 billion but less than $14 billion in additional federal relief funding, the specified amounts provided to the universities are proportionally reduced.)

Cost Shifts and Borrowing

Special Fund Loans and Transfers. In past recessions, the state made loans from other state accounts, known as special funds, to the General Fund to address budget problems. The General Fund must eventually repay these loans with interest. The spending plan again makes use of this tool, making $3 billion in loans from a wide range of special funds. Included with these loans is control section language that lends special fund savings from lower employee compensation costs in 2020‑21 to the General Fund. The administration estimates this would yield nearly $1 billion in loans. (These loans would be undone if more federal funding is forthcoming, per the trigger language discussed earlier.) Finally, the budget transfers about $100 million in special fund balances to the General Fund—amounts that would not be repaid.

Shift Pension Costs. The budget takes actions in a few pension‑related areas that result in cost shifts from the present to the future. First, the 2019‑20 budget made a supplemental pension payment of $2.5 billion to CalPERS. The state would have realized savings over the next few decades from this payment, eventually resulting in an estimated gross savings of $5.9 billion. The budget repurposes this supplemental payment to supplant state General Fund contributions to CalPERS this year. This results in savings of $2.4 billion, which the budget scores over multiple years including 2021‑22, but foregoes the future savings, thus resulting in higher ongoing costs. Second, the budget suspends CalSTRS’ ability to increase the state’s contribution rate in 2020‑21. (Currently, CalSTRS can only increase the state’s rate by 0.5 percent per year—equivalent to $169 million in 2020‑21.) Instead, the budget provides offsetting payments to CalSTRS using other required debt payments. Finally, the budget eliminates a $265 million supplemental payment to CalPERS planned for 2020‑21 under current law. The spending plan also uses Proposition 2 required debt payments to pay for a $243 million unfunded liability pension payment for California Highway Patrol, thereby reducing General Fund costs.

Shifts Roughly $700 million in Costs to Lease Revenue Bonds (LRBs). Recent budgets have set aside General Fund monies to pay for some capital outlay projects. For example, the state has set aside nearly $1 billion in the State Project Infrastructure Fund (SPIF) for the renovation of the State Capitol Annex and the construction of a new office building near the State Capitol. The spending plan converts $694 million from the SPIF and some other smaller projects to LRB financing. As a result, the state will borrow from the bond market to pay the upfront costs of these projects and then repay those bonds with interest over time. This results in savings of roughly $700 million in 2020‑21, but higher debt service costs over time.

COVID‑19 Spending

State Spending on COVID‑19

$2.2 Billion Allocated Under DREOA, SB 89, and SB 117. Before the final budget process began in May, the state incurred about $2.2 billion in COVID‑19 expenditures under the authority provided by SB 89, SB 117, and DREOA (as described earlier). These funds were allocated to fulfill a wide variety of state needs, including procuring medical supplies and personal protective equipment, preventing and containing COVID‑19 among homeless individuals, and providing services to at‑risk individuals. The spending plan anticipates the federal government eventually will reimburse the state for an estimated 75 percent of most of these costs under the federal disaster declarations.

$3.5 Billion in Direct COVID‑19‑Related Expenditures Allocated in the Budget. The budget package also allocates an additional $3.5 billion in direct COVID‑19‑related expenditures. These funds are allocated for similar purposes as the prior amounts, including procuring personal protective equipment, expanding hospital and medical surge capacity, providing hotels for healthcare workers who come into contact with COVID‑19 patients, and statewide testing and contact tracing. The budget package assumes the federal government will reimburse the state for 75 percent for most of these costs.

$716 Million for COVID‑19 Contingencies in the SFEU. In the May Revision, the Governor proposed that the Legislature set aside $2.9 billion in a fund that the Governor could access for future COVID‑19‑related expenses. The final spending plan does not include the contingency fund, but does designate $716 million in the SFEU for this purpose. (There is no formal subaccount or budget language providing appropriation authority for this funding.) Because these funds are not appropriated, the budget plan does not assume there are any associated federal reimbursements.

Federal Coronavirus Relief Fund

Budget Allocates $9.5 Billion in CRF. Congress established the CRF to provide money to state, local, tribal, and territorial governments for “necessary expenditures incurred due to the public health emergency with respect to the Coronavirus Disease 2019” that are incurred between March 1 and December 30, 2020. California’s state government received $9.5 billion from the CRF. (Cities and counties in California with populations greater than 500,000 also received $5.8 billion in CRF directly from the federal government.) Guidance from the U.S. Department of the Treasury (U.S. Treasury) outlines the eligible uses of these funds. The spending plan allocates the state’s CRF funds to the following purposes:

- Schools and Community Colleges. The budget allocates $4.5 billion to K‑14 entities to mitigate the effects of school closures related to COVID‑19. For example, schools and community colleges will be able to use this funding to pay for increased costs related to: summer school, additional instructional time, and other services and supports for students.

- State Programs. The budget allocates $2.7 billion in CRF funds to offset state costs in a variety of programs, for example in public safety, public health, and for increased costs of certain caseload‑driven programs (in particular, CalWORKs).

- Counties. The budget provides $1.3 billion to counties to be used toward homelessness, public health, public safety, and other services to combat the COVID‑19 pandemic. These funds are allocated according to each county’s share of the state’s population, but require counties to comply with the state’s public health orders to receive them.

- Homelessness Programs. The budget allocates $550 million to the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) for Project Homekey, intended to provide housing for individuals and families who are experiencing homelessness or who are at risk of homelessness due to the COVID‑19 pandemic. We discuss this funding in more detail in the section below on local government funding.

- Cities. The budget provides $500 million to cities for homelessness, public health, public safety, and other services to combat the COVID‑19 pandemic. Of this total, $225 million is provided to cities with populations greater than 300,000 that did not receive a direct federal allocation and $275 million is provided to cities with a population of less than 300,000.

Control Section Language Gives Administration Discretion to Reallocate CRF Monies. Under federal law and U.S. Treasury policy, if any states’ CRF funds are unspent at the end of 2020, they must revert back to the U.S. Treasury. As such, the budget authorizes the Director of Finance to reallocate the funding to other allowable activities if CRF funds are not spent before September 1, 2020. The language requires a ten‑day notification to the Joint Legislative Budget Committee.

Other Major Features

Safety Net Programs

Medi‑Cal. The spending plan allocates $115.4 billion total funds ($23.6 billion General Fund) in 2020‑21 to Medi‑Cal local assistance in the Department of Health Care Services. This reflects an increase of $15.9 billion total funds—or 16 percent—over 2019‑20 estimated spending. (General Fund spending increases by a much more modest 4 percent.) Caseload in the program is projected to grow by 9 percent between 2019‑20 and 2020‑21—from 13 million to 14.2 million—largely due to the projected impact of COVID‑19. This COVID‑19‑related projected caseload growth results in a $6.1 billion ($2.1 billion General Fund) year‑over‑year increase in projected program expenditures. However, two major adjustments significantly offset this and other cost‑related changes in Medi‑Cal. First, the federal government approved the state’s recently reauthorized managed care organization (MCO) tax for the period of January 1, 2020 through June 30, 2023. Revenues from the new MCO tax offset about $1.7 billion in General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal in 2020‑21. Second, Congress approved a 6.2 percentage‑point increase in the federal government’s share of cost for Medicaid (Medi‑Cal is the state’s Medicaid program) for the duration of the national public health emergency caused by COVID‑19. The spending plan assumes this enhanced federal funding is in place through the end of 2020‑21 and will offset around $2.8 billion in General Fund spending in Medi‑Cal in 2020‑21.

In‑Home Supportive Services (IHSS). The budget projects IHSS total costs to increase from $13.6 billion in 2019‑20 to $15.2 billion in 2020‑21 (11.7 percent). General Fund costs are estimated to slightly increase between 2019‑20 ($4.3 billion) and 2020‑21 ($4.5 billion). This slight year‑to‑year increase in General Fund expenditures masks a number of cost increases and costs shifts. Specifically, the budget assumes continued year‑to‑year growth to the three primary IHSS cost drivers: caseload (4.1 percent), hours per case (1.5 percent), and IHSS provider hourly wages and benefits (6.5 percent). Additionally, the budget rejects the administration’s May Revision proposal to reduce IHSS service hours by 7 percent effective January 1, 2021, resulting in a cost of $205 million General Fund in 2020‑21. Similar to Medi‑Cal, total IHSS General Fund costs are partially offset by a temporary increase in the federal government’s share of IHSS costs for the duration of the national public health emergency—an estimated total of $1.2 billion of IHSS General Fund savings across 2019‑20 and 2020‑21.

CalWORKs. CalWORKs provides cash assistance, child care, and employment services to low‑income families with children. Generally speaking, CalWORKs caseload and costs increase during and following economic recessions and decrease during economic expansions. The all‑time high for CalWORKs caseload (587,000 cases per month) was reached in 2010‑11 in the immediate wake of the Great Recession. In response to the COVID‑19 public health emergency and recession, as part of the May Revision proposal, the administration projected the CalWORKs caseload would increase well above this previous high, averaging about 725,000 cases in 2020‑21 (about twice the caseload projected in the Governor’s January budget proposal). The final budget projects a lower CalWORKs caseload—instead equaling the previous all‑time high of 587,000 in 2020‑21. Because grant levels are higher now than during the previous recession, total CalWORKs costs are projected to reach $7.8 billion (as compared to about $6.3 billion in 2010‑11).

Funding for Local Governments

In addition to the CRF funding provided to local governments, which is described in the previous section, the spending plan allocates General Fund monies to local governments for a variety of purposes, in particular realignment and housing. This section describes these programs in more detail.

Budget Partially Backfills Projected Realignment Revenue Declines. The 1991 and 2011 realignments dedicated state sales tax and vehicle license fee revenue to counties for the administration of various programs on behalf of the state. The budget provides $750 million to backfill anticipated declines in realignment revenue in 2020‑21. An additional $250 million would be available through a trigger mechanism if the state receives additional federal funding by October 15, 2020. Associated budget bill language directed the California State Association of Counties to work with DOF to determine the funding allocation. Additionally, the language allowed the funding to be used to prioritize support for health, human services, entitlement programs, and programs that serve vulnerable populations. The selected methodology, allocates funding to each county in proportion to the amount of realignment funding shortfall each county is facing, which is consistent with how funding would have been allocated if it flowed through existing realignment formulas. As a condition of receiving the funding, counties must show that they are in compliance with state and federal public health requirements.

Budget Provides $600 Million for Project Homekey and Related Services. At the outset of the COVID‑19 pandemic, the state provided $50 million for the newly established Project Roomkey. The program helped local governments acquire hotels and motels to provide for the immediate housing needs of vulnerable individuals experiencing homelessness that were at risk of contracting COVID‑19. Building off Project Roomkey, the 2020‑21 spending plan provides $550 million of the state’s direct allocation of federal CRF for Project Homekey. Project Homekey provides for the acquisition of hotels, motels, residential care facilities, and other housing that can be converted and rehabilitated to provide permanent housing for persons experiencing homelessness or at risk of homelessness, and who also are impacted by COVID‑19. Through HCD, the state will provide grants to local governments to acquire these facilities, which will be owned and operated at the local level. The 2020‑21 budget also provides an additional $50 million General Fund for the acquisition, conversion, rehabilitation, and operation of Project Homekey sites. Associated trailer bill language provides exemptions to the California Environmental Quality Act and local zoning restrictions to expedite the acquisition of Project Homekey sites prior to the December 30, 2020 deadline to expend CRF funds.

Budget Provides $300 million to Continue the Homeless Housing, Assistance, and Prevention (HHAP) Program. The 2019‑20 budget provided $650 million for one‑time grants to cities, counties, and Continuums of Care (CoCs) to fund a variety of programs and services that address homelessness through the HHAP program. The 2020‑21 budget provides an additional $300 million General Fund for a one‑time continuation of HHAP. Specifically, the budget makes $130 million available for cities with populations of 300,000 or more, $90 million available for CoCs, and $80 million available for counties. To receive funds, the eligible entities must provide a plan to the Homeless Coordinating and Financing Council describing how they have coordinated, and will continue to coordinate, with other local agencies to address homelessness in their region. The funding may be used to operate Project Homekey sites and for evidence‑based solutions, including rapid rehousing, rental subsidies, and subsidies for new and existing housing and emergency shelters.

Other

Reductions in Employee Compensation. As part of the 2020‑21 spending plan, the Legislature directed the administration to, through budget related legislation, reduce state employee compensation costs by up to 10 percent to achieve the savings assumed in the budget. Specifically, under Control Section 3.90, the 2020‑21 budget assumes savings of $2.8 billion ($1.5 billion for the General Fund) resulting from reductions in employee compensation. The Legislature (1) directed the administration to seek to achieve these savings through the collective bargaining process and (2) authorized the administration to impose furloughs if the administration and unions could not reach agreement. The administration reached agreement with all 21 of the state’s bargaining units in June and July 2020 to reduce state employee compensation costs in 2020‑21. As part of the budget package, the Legislature ratified the agreements with all 21 bargaining units. We released an analysis on September 9, 2020 that (1) provides a historical record of all the labor agreements between the state and its employees to reduce state costs in 2020‑21 and (2) looks forward and provides comments and recommendations to help the Legislature think through future decisions to reduce employee compensation should the budget problem persist beyond 2021‑22.

Includes Major Prison and Parole Changes Leading to Savings in Future Years. The budget includes the following major changes to the prison and parole systems that will result in significant savings in future years.

- Makes Changes to Reduce the Prison Population. The budget reflects various changes intended to further reduce the prison population. For example, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) plans to (1) reduce the time it takes to identify housing for newly received inmates—allowing them to access rehabilitation programs earlier and earn more time off their prison terms—and (2) increase the amount of time certain inmates earn off their prison terms through good behavior. These two changes are estimated to reduce the inmate population by nearly 11,000 inmates by 2023‑24. The budget assumes that these changes will create $6.4 million in savings in 2020‑21. Savings will likely increase to hundreds of millions of dollars within a few years.

- Includes Plan to Close Two Prisons by 2022‑23. The administration has indicated it plans to close one prison in 2021‑22 and another in 2022‑23 in order to accommodate the ongoing decline in the inmate population, primarily resulting from Proposition 57 (2016). The budget package includes legislation requiring CDCR to inform the Legislature of the specific prisons to be closed by January 10, 2021 and January 10, 2022. The administration estimates the closures will result in $400 million in ongoing savings annually within a few years. (Proposition 57 reduced the amount of time inmates serve in prison primarily by increasing CDCR’s authority to reduce inmates’ sentences, such as for completion of rehabilitation programs.)

- Makes Changes to Reduce the Parole Population. The budget package includes legislation capping parole terms for many parolees at two to three years and establishing an early discharge process. Due to these changes, the budget assumes $23.2 million in reduced parole expenditures in 2020‑21, increasing to roughly $76 million in ongoing savings within a few years.

Plan to Realign Division of Juvenile Justice. The budget reflects the approval of a May Revision proposal to gradually “realign” or shift the responsibility of the Division of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) for housing certain juvenile offenders from the state to the counties. Beginning July 1, 2021, youth who would otherwise be sent to DJJ would generally be placed under county supervision. Accordingly, the budget package provides $9.6 million General Fund—increasing to $209 million annually by 2024‑25—to assist counties with their increased responsibilities. These costs would be at least partially offset in future years from state savings related to reductions in the DJJ population.

Supports Community Resilience During Power Shutdowns. The budget provides $50 million General Fund on a one‑time basis to mitigate the effects of power shutdowns implemented to reduce the risk of wildfires sparked by utility‑owned equipment.

Local Air District AB 617 Implementation. The spending plan includes $50 million one‑time (Air Pollution Control Fund) to continue support for local air district costs of implementing Chapter 136 of 2017 (AB 617, C. Garcia). Local air district costs include maintaining air monitoring equipment and developing and implementing community air protection plans.