LAO Contact

February 22, 2023

The 2023-24 Budget

California Community Colleges

Summary

Brief Covers the California Community Colleges (CCC). This brief analyzes the Governor’s budget proposals relating to enrollment, apportionments, and facilities maintenance. It also describes funding protections for district apportionments under the Student Centered Funding Formula (SCFF) and identifies a potential funding shortfall in the Governor’s budget.

Opportunities Exist to Repurpose Enrollment Funds for Other Proposition 98 Priorities. Consistent with nationwide trends, community colleges in California experienced significant enrollment declines during the pandemic. In response, recent state budgets have provided districts with funding to grow their enrollment. Based on preliminary data, districts will not end up earning some of this enrollment growth funding. We recommend the Legislature sweep any unearned growth funds for other Proposition 98 purposes and use updated enrollment data this spring to help decide how much growth funding to provide in the budget year. In addition, given the substantial funding still available to districts for student outreach, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to provide an additional $200 million one time for this purpose by reducing funding in the current‑year budget for facility maintenance. We recommend the Legislature effectively retain those funds for facility maintenance projects, as most of those funds already have been distributed to districts and committed to projects that would reduce their maintenance backlogs.

State Likely Has Limited Capacity to Fund an Even Higher Cost‑of‑Living Adjustment (COLA). The largest community college proposal in the Governor’s budget is $653 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund for an 8.13 percent COLA for apportionments (general purpose funding). Based upon new data, the estimated COLA rate is even higher (8.40 percent). In 2023‑24, districts are facing considerable pressure to increase employees’ salaries given high inflation, while also facing other core operating cost increases. Despite these challenges, we are concerned with the state’s ability to support a higher COLA rate given its budget condition. We recommend the Legislature treat the 8.13 percent COLA rate as an upper bound for 2023‑24 and consider providing a lower rate depending on updated estimates of the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee in May.

Confusion Over “Stability Funding” Is Resulting in Significant Cost Differences. SCFF, which was adopted by the Legislature in 2018‑19 as a new way of allocating apportionment funds to districts, includes a number of funding protections. One of those protections, known as stability funding, is intended to provide a cushion to local budgets resulting from enrollment and other declines. As currently written, the statutory provision describing stability funding is confusing and difficult to understand. This lack of clarity has resulted in the administration and Chancellor’s Office interpreting the provision differently and having different associated cost estimates. Whereas the Governor’s budget includes no stability funding for 2023‑24, the Chancellor’s Office believes the associated cost would be $134 million. Given both the administration’s and Chancellor’s Office’s interpretations are problematic, we recommend the Legislature modify statute and adopt an alternative way to calculate stability funding. Our alternative serves the state’s long‑standing policy objective of protecting districts from sudden funding declines while avoiding the problematic funding outcomes that arise under the other two interpretations. Given timing issues, the Legislature has a couple of options it could consider regarding stability funding in the budget year.

Introduction

This brief analyzes the Governor’s major budget proposals for CCC. We begin by describing the Governor’s overall budget plan for CCC. The remaining four sections of the brief focus on enrollment, apportionments, SCFF funding protections, and facilities maintenance, respectively. This brief is part of our series of higher education budget analyses. The 2023‑24 Budget: Higher Education Overview was our first brief in this series, with subsequent briefs delving more deeply into each of the segments’ budgets.

Overview

Total CCC Funding Is $17.5 Billion Under Governor’s Budget. As Figure 1 shows, $12.6 billion (72 percent) of CCC support in 2023‑24 would come from Proposition 98 funds. Proposition 98 funds consist of state General Fund and certain local property tax revenue that cover community colleges’ main operations. An additional $963 million non‑Proposition 98 General Fund would cover certain other costs, including debt service on state general obligation bonds for CCC facilities, a portion of CCC faculty retirement costs, and operations at the Chancellor’s Office. In recent years, the state also has provided non‑Proposition 98 General Fund for certain student housing projects.

Figure 1

California Community Colleges Rely Heavily on Proposition 98 Funding

(Dollars in Millions, Except Funding Per Student)

|

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

2023‑24 |

Change From 2022‑23 |

||

|

Amount |

Percent |

||||

|

Proposition 98 |

|||||

|

General Fund |

$8,790 |

$8,713 |

$8,758 |

$45 |

0.5% |

|

Local property tax |

3,512 |

3,648 |

3,811 |

164 |

4.5 |

|

Subtotals |

($12,301) |

($12,360) |

($12,569) |

($209) |

(1.7%) |

|

Other State |

|||||

|

Other General Fund |

$653 |

$1,166a |

$963a |

‑$203 |

‑17.4% |

|

Lottery |

302 |

264 |

264 |

—b |

‑0.1 |

|

Special funds |

81 |

95 |

95 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($1,036) |

($1,525) |

($1,322) |

(‑$203) |

(‑13.3%) |

|

Other Local |

|||||

|

Enrollment fees |

$409 |

$409 |

$411 |

$1 |

0.3% |

|

Other local revenuec |

2,821 |

2,845 |

2,867 |

22 |

0.8 |

|

Subtotals |

($3,230) |

($3,255) |

($3,278) |

($23) |

(0.7%) |

|

Federal |

|||||

|

Federal stimulus fundsd |

$2,648 |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Other federal funds |

365 |

$365 |

$365 |

— |

— |

|

Subtotals |

($3,014) |

($365) |

($365) |

(—) |

(—) |

|

Totals |

$19,581 |

$17,506 |

$17,535 |

$29 |

0.2% |

|

FTE studentse |

1,107,128 |

1,106,951 |

1,106,451 |

‑500 |

—f |

|

Proposition 98 funding per FTE studente |

$11,111 |

$11,166 |

$11,360 |

$194 |

1.7% |

|

aIncludes $564 million in 2022‑23 and $363 million in 2023‑24 for student housing grants. |

|||||

|

bDifference of less than $500,000. |

|||||

|

cPrimarily consists of revenue from student fees (other than enrollment fees), sales and services, and grants and contracts, as well as local debt‑service payments. |

|||||

|

dConsists of federal relief funds provided directly to colleges as well as allocated through state budget decisions. |

|||||

|

eReflects budgeted rather than actual FTE students. Actual FTE students are notably lower each year of the period, but certain budget provisions are insulating districts from associated funding declines. |

|||||

|

fReflects the net change (‑0.05 percent) after accounting for the proposed 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth together with all other enrollment adjustments. |

|||||

|

FTE = full‑time equivalent. |

|||||

Beyond State Funds, Community Colleges Receive Support From Various Other Sources. Much of CCC’s remaining funding comes from student fees, including enrollment fees, and various local sources (such as revenue from facility rentals and community service programs). The Governor proposes no increase to enrollment fees for 2023‑24, which since summer 2012 have been $46 per unit (or $1,380 for a full‑time student taking 30 semester units per year). During the initial years of the pandemic, community colleges also received a significant amount of federal relief funds, as discussed in the box nearby.

Federal Relief Funds

Community Colleges Received Considerable Federal Relief Funding. Community colleges received a total of $4.7 billion over three rounds of federal relief funding in response to COVID‑19. (Our Federal Relief Funding for Higher Education table provides more detail on California Community Colleges relief funds.) Collectively, colleges are required to spend at least $2 billion of their relief funds for direct student aid. The rest can be used for institutional operations. Colleges have used institutional funds for a variety of purposes, including to undertake screening and other COVID‑19 mitigation efforts, cover higher technology costs related to remote operations, acquire laptops for students, and backfill lost revenue from parking and other auxiliary college programs.

Deadline for Colleges to Spend Federal Relief Funds Is Approaching. Initially, colleges had to spend their federal relief funds by May 2022. In March 2022, the federal government granted an extension, giving all colleges until June 30, 2023 to spend their remaining funds. Systemwide data on community college expenditures is not readily available and, as of this writing, the federal reporting portal only shows individual college expenditures through November 30, 2022. A review of a subset of colleges, however, indicates that many colleges have spent all or nearly all of their institutional and student aid funds. In some cases, however, colleges have purposely spread out their spending so that they still have institutional and student aid funds available in the first half of 2023.

Last Year’s CCC Budget Cushion Allows for More Growth in Ongoing Spending This Year. Proposition 98 support for CCC increases by $209 million (1.7 percent) over the revised 2022‑23 level. Despite the growth rate being lower than 2 percent, the Governor’s budget still is able to support a substantial increase in ongoing community college spending. The main reason this is possible is because the state provided nearly $700 million one‑time CCC funding in 2022‑23 that counted toward the minimum guarantee. All of this one‑time funding becomes freed up in 2023‑24 for other purposes. Under the Governor’s budget, these funds are repurposed primarily for community college apportionments.

Governor’s Largest Proposal Is Providing a COLA to Apportionments. Unlike the past several years when the Governor had many Proposition 98 ongoing and one‑time spending proposals for the colleges, the Governor’s budget this year contains relatively few proposals. As Figure 2 shows, the largest ongoing Proposition 98 proposal is $653 million for an 8.13 percent COLA for apportionments. In addition, the Governor’s budget provides an 8.13 percent COLA for select categorical programs, at a total cost of $92 million, and $29 million for 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth. The Governor’s largest one‑time CCC spending proposal is for student enrollment and retention strategies. The Governor’s budget includes a reduction for previously authorized spending on facilities maintenance. The administration indicates that this reduction is intended to cover the cost of its enrollment and retention proposal, which it sees as a higher priority for the colleges in the budget year. The Governor’s budget also provides CCC with $14 million in one‑time reappropriated Proposition 98 funds for forestry workforce development grants, as discussed in the box below.

Figure 2

Governor Has a Few Proposition 98

Community College Spending Proposals

(In Millions)

|

Ongoing Spending |

|

|

COLA for apportionments (8.13 percent) |

$653 |

|

COLA for select categorical programs (8.13 percent)a |

92 |

|

Enrollment growth (0.5 percent) |

29 |

|

FCMAT new professional development program |

—b |

|

Subtotal |

($774) |

|

One‑Time Initiatives |

|

|

Student enrollment and retention strategies |

$200 |

|

Forestry/fire protection workforce training |

14c |

|

FCMAT new professional development program |

—b |

|

Facilities maintenance and instructional equipment |

‑$213d |

|

Subtotal |

($1) |

|

Total Changes |

$775 |

|

aApplies to the Adult Education Program, apprenticeship programs, CalWORKs student services, campus child care support, Disabled Students Programs and Services, Extended Opportunity Programs and Services, and the mandates block grant. |

|

|

bConsists of $200,000 in ongoing funds and $75,000 in one‑time funds. |

|

|

cUses reappropriated Proposition 98 funds (previously appropriated funds for other purposes that were not spent). |

|

|

dReduces funding provided in the 2022‑23 budget agreement for this purpose from a total of $841 million to $628 million. |

|

|

COLA = cost‑of‑living adjustment and FCMAT = Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team. |

|

Forestry Workforce

Governor Proposes to Shift Fund Source for Workforce Development Grants. In response to a projected state budget deficit, the Governor proposes many budget solutions. One of these solutions is to shift some costs from the non‑Proposition 98 side of the budget to the Proposition 98 side. Specifically, the Governor proposes to reduce non‑Proposition 98 General Fund support for existing workforce training grants administrated by the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (CalFire) by $15 million, replacing it with nearly the same amount of reappropriated Proposition 98 General Fund support ($14 million). Under the Proposition 98‑funded program, the California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office would enter an interagency agreement with CalFire to administer the grant program. Grants would be limited to community colleges. By comparison, a broader group of training providers (including local workforce agencies, nonprofits organizations, and community colleges) may participate in the existing CalFire program.

Fund Shift Is Worth Considering Given General Fund Condition. The proposed fund shift would help address the state’s non‑Proposition 98 budget deficit. Moreover, community colleges already have an important role in helping develop the forestry workforce. Currently, 8 community colleges offer associate degree or certificate programs in forestry, and 55 colleges offer them in fire technology or wildland fire technology. Together, these community colleges have granted about 100 forestry associate degrees and certificates, as well as about 2,500 fire and wildland fire technology associate degrees and certificates annually in recent years. Community colleges also have received a portion of the past grant funding from this CalFire workforce development program ($2.3 million of $18 million appropriated in 2021‑22). Providing community colleges with additional workforce training grants would take advantage of colleges’ existing expertise and experience in the forestry area. Though limiting grants to community colleges would exclude other workforce providers, we think the fund shift remains reasonable given the other factors described above. In The 2023‑24 Budget: Crafting Climate, Resources, and Environmental Budget Solutions we discuss this proposal, along with other proposed budget solutions in the natural resources area.

Funds Ten Continuing Capital Projects. The Governor proposes to provide $144 million in state general obligation bond funding to continue ten previously authorized community college projects. Each project is funded for the construction phase. About $90 million of bond funds would come from Proposition 51 (2016), with the remaining bond funds coming from Proposition 55 (2004). A list of these projects and their associated costs is available on our EdBudget website.

Governor Intends to Present a Categorical Program Flexibility Proposal in Spring. The Governor’s Budget Summary signals a desire to provide community colleges with more spending and reporting flexibility for certain categorical programs. The administration indicates that more details, including which categorical programs would be included in such a flexibility proposal, will be provided in the spring.

Enrollment

In this section, we provide background on community college enrollment trends, describe the Governor’s proposals to fund enrollment growth as well as additional student outreach, assess those proposals, and offer associated recommendations.

Background

Several Factors Influence CCC Enrollment. Under the state’s Master Plan for Higher Education and state law, community colleges operate as open access institutions. That is, all persons 18 years or older may attend a community college. (While CCC does not deny admission to students, there is no guarantee of access to a particular class.) Many factors affect the number of students who attend community colleges, including changes in the state’s population, particularly among young adults; local economic conditions, particularly the local job market; the availability of certain classes; and the perceived value of the education to potential students.

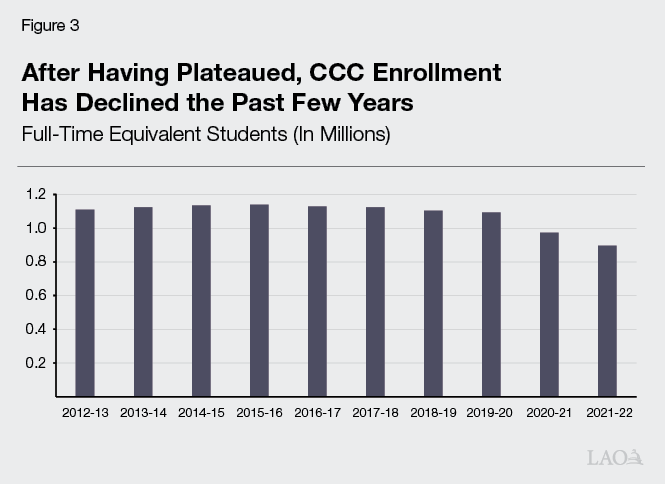

Prior to the Pandemic, CCC Enrollment Had Plateaued. Following the Great Recession, as the economy and state funding began recovering (2012‑13 through 2015‑16), systemwide CCC enrollment grew. As Figure 3 shows, CCC enrollment flattened thereafter. The plateau in CCC enrollment during this period was commonly attributed to the long economic expansion, strong labor market, and unemployment remaining at or near record lows.

CCC Enrollment Has Dropped Notably Since Start of Pandemic. As Figure 3 also shows, between 2018‑19 (the last full year before the start of the pandemic) and 2021‑22, full‑time equivalent (FTE) students at CCC declined by more than 200,000 (19 percent). The drop in CCC enrollment has been consistent with nationwide community college enrollment trends over this period. While CCC enrollment declines have affected virtually every student demographic group, most districts report the largest enrollment declines among African American, male, lower‑income, and older adult students. These group‑specific impacts also are consistent with nationwide trends.

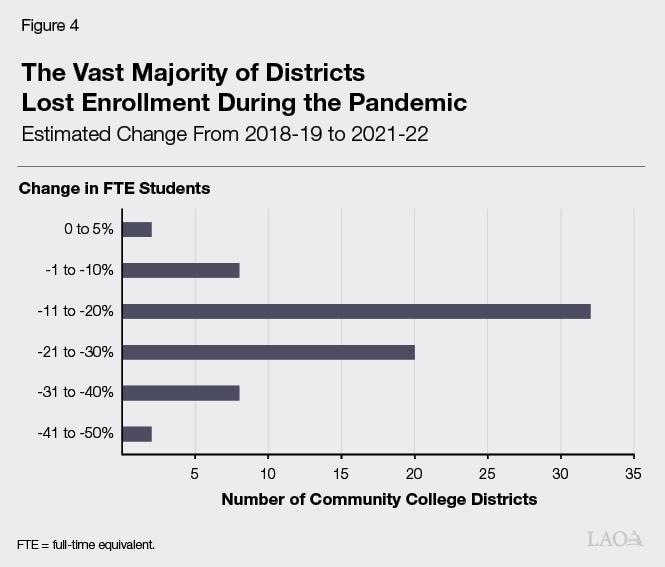

Enrollment Declines Have Affected Nearly Every District. Figure 4 shows most community college districts experienced enrollment declines between 2018‑19 and 2021‑22. Thirty‑two districts (nearly half of all districts) experienced declines between 11 percent and 20 percent, with another 30 districts experiencing declines of more than 20 percent. Several of the districts with especially heavy enrollment loss had been experiencing enrollment declines prior to the pandemic due to factors such as declining population in the region or well‑publicized accreditation problems. The districts that grew or had relatively small enrollment declines during this period were a mix of urban, suburban, and rural districts. Several of these districts increased enrollment among nontraditional students, including dually enrolled high school students and incarcerated students.

Several Factors Likely Contributing to Enrollment Drops. Enrollment drops nationally and in California have been attributed to various factors. Over the past couple of years, rising wages, including in low‑skill jobs, and an improved job market appear to be major causes of reduced community college enrollment demand. In response to a fall 2021 Chancellor’s Office survey of former and prospective students, many respondents cited “the need to work full time” to support themselves and their families as a key reason why they were choosing not to attend CCC. For these individuals, enrolling in a community college and taking on the associated opportunity cost might have become a lower priority than entering or reentering the job market.

Colleges Have Been Trying a Number of Strategies to Attract Students. Using federal relief funds, as well as state funds provided in 2021‑22 and 2022‑23, colleges have been trying various strategies to attract students. All colleges have been offering students special forms of financial assistance. For example, all colleges provided emergency grants to financially eligible students that could be used for any living expense. Some colleges are offering gas cards or book and meal vouchers to students who enroll. Many colleges are loaning laptops to students. Many colleges have expanded advertising through social media and other means, including in languages other than English. Additionally, many colleges have increased outreach to local high schools, and many colleges have created phone banks to contact individuals who recently dropped out of college or had completed a CCC application recently but did not register for classes. In addition, a number of colleges have begun to offer more flexible courses, with shorter terms and more opportunities to enroll throughout the year (rather than only during typical semester start dates).

Proposals

Governor’s Budget Funds Enrollment Growth. The Governor’s budget includes $29 million ongoing Proposition 98 General Fund for 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth (equating to about 5,500 additional FTE students) in 2023‑24. The state also provided funding for 0.5 percent systemwide enrollment growth in 2022‑23 and 2021‑22. Consistent with regular enrollment growth allocations, each district in 2023‑24 would be eligible to grow up to 0.5 percent. To be eligible for these growth funds, however, a district must first recover to its pre‑pandemic enrollment level. Provisional budget language would allow the Chancellor’s Office to allocate ultimately unused growth funding to backfill any shortfalls in CCC apportionment funding, such as ones resulting from lower‑than‑estimated enrollment fee revenue or local property tax revenue. The Chancellor’s Office could make any such redirection after underlying apportionment data had been finalized, which would occur after the close of the fiscal year. This is the same provisional language the state has adopted in recent years. After addressing any apportionment shortfalls, remaining unused funding may be redirected to any other Proposition 98 purpose.

Governor Proposes Another Round of One‑Time Funding to Boost Outreach to Students. The Governor proposes $200 million one‑time Proposition 98 General Fund for student enrollment and retention strategies. This is on top of the $120 million one time provided in 2021‑22 and $150 million one time provided in 2022‑23 specifically for this purpose. The proposed provisions for the new round of funding are the same as the provisions adopted for the earlier rounds of funding. Like the last two rounds of funding, the purpose of these proposed funds is for colleges to reach out to former students who recently dropped out and engage with prospective or current students who might be hesitant to enroll or reenroll at the colleges. Provisional language gives the Chancellor’s Office discretion on the allocation methodology for the funds but would require that colleges experiencing the largest enrollment declines be prioritized. The provisional language also permits the Chancellor’s Office to set aside and use up to 10 percent of the funds for statewide enrollment and retention efforts.

Assessment

Likely That Most 2021‑22 Growth Funding Will Not Be Earned by Districts. As of June 2022 reporting by the Chancellor’s Office, only about $1 million of $24 million in 2021‑22 enrollment growth funding had been earned by districts. That same report also identified no apportionment funding shortfalls. The Chancellor’s Office plans to release final 2021‑22 enrollment and funding data by the end of February 2023. Any 2021‑22 growth funds not earned by districts or needed for a funding shortfall would become available for other Proposition 98 purposes, including other community college purposes or Proposition 98 budget solutions.

Better Information Is Coming on 2022‑23 Enrollment Situation. As of this writing, forecasting 2022‑23 community college enrollment is difficult given that the Chancellor’s Office is still processing fall 2022 district enrollment submissions and the spring 2023 term is just beginning. (Based on preliminary data, systemwide fall 2022 enrollment could be flat or up somewhat compared to fall 2021, though a number of districts continue to report enrollment declines.) By the time of the May Revision, the Chancellor’s Office will have provided the Legislature with initial 2022‑23 enrollment data. This data will show which districts are reporting enrollment declines and the magnitude of those declines. It also will show whether any districts are on track to earn any of the 2022‑23 enrollment growth funds. Apportionment data for 2022‑23, however, will not be finalized until February 2024, such that the Legislature might not want to take any associated budget action until next year. At that time, if the entire 2022‑23 enrollment growth amount ends up not being earned by districts or needed for any apportionment shortfalls, the Legislature could redirect available funds for other Proposition 98 purposes, including potential Proposition 98 budget solutions.

Best Indicator for 2023‑24 Enrollment Likely Will Be Updated Data on Current Year. If some districts are on track to grow in the current year, it could mean they might continue to grow in the budget year. By providing funding for enrollment growth in 2023‑24, the state could encourage and reward districts for expanding access to students.

Substantial Amount of Round‑Two Student Outreach Funding Remains Available. The state is not collecting CCC systemwide data on student outreach expenditures. However, based on our discussions with numerous administrators, districts will have funds still available from 2022‑23 allocations for outreach and retention. Districts generally are wrapping up spending of 2021‑22 funds for this purpose and just beginning to spend 2022‑23 funds. Existing provisional language allows districts to spend these second‑round funds through the budget year. In addition, districts have four more years (though 2026‑27) to spend a total of $650 million in state COVID‑19 block grant funds, which statute also allows colleges to use for enrollment and retention‑related purposes. (The Chancellor’s Office must report to the Legislature by March 2024 on initial district spending and outcomes using COVID‑19 block grant funds.)

Mixed Results on Student Outreach Funding to Date. Some districts might see enrollment increases in 2022‑23, though the link to 2021‑22 student outreach funds still is not well documented. Moreover, many districts expect to continue experiencing enrollment declines in 2022‑23 despite the first‑round of student outreach funds. Districts may not be able to counter the underlying economic factors they face to a notable degree. Over time, CCC enrollment has shown a close correlation with the job market, with a strong job market depressing CCC enrollment demand. Spending on advertising, phone calls, and other forms of outreach might not be sufficient to overcome these more fundamental drivers of CCC enrollment. However, to the extent districts consider these outreach and related activities effective in increasing enrollment, they can supplement their remaining student outreach funds with apportionment funding.

Recommendations

Sweep 2021‑22 Growth Funds. Once 2021‑22 enrollment and funding data are finalized, we recommend the Legislature redirect any unearned enrollment growth funds for other Proposition 98 priorities. Based upon preliminary data, $23 million would be available for other priorities.

Use Forthcoming Data to Decide Enrollment Growth Funding for 2023‑24. We recommend the Legislature also use updated enrollment data, as well as updated data on available Proposition 98 funds, to make its decision on CCC enrollment growth for 2023‑24. If the updated enrollment data indicate some districts are growing in 2022‑23, the Legislature could view growth funding in 2023‑24 as warranted. Were data to show that no districts are growing, the Legislature still might consider providing some level of growth funding given that enrollment potentially could start to rebound next year. Moreover, the risk of overbudgeting in this area is low, as any unearned funds ultimately become available for other Proposition 98 purposes.

Reject Proposal for More Enrollment and Retention Funding. We recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s student outreach proposal. Given substantial round‑two student outreach funding remains available, along with a substantial amount of other funding that can be used for student outreach, a strong case has not been made that additional funding is needed at this time. The Legislature could repurpose the associated $200 million in one‑time funding for other high one‑time Proposition 98 priorities or Proposition 98 budget solutions. (In the following sections, we identify some possible Proposition 98 uses that the Legislature could consider.)

Apportionments

In this section, we provide background on community college apportionments, describe the Governor’s proposal to provide a COLA for apportionments, assess the proposal, and provide a recommendation.

Background

Most CCC Proposition 98 Funding Is Provided Through Apportionments. All community college districts (except the statewide online Calbright College) receive apportionment funding. Apportionment funding is unrestricted, with colleges able to use the funding for their core operating costs. Although the state is not statutorily required to provide a COLA for apportionments (as it is for school districts), the state has a long‑standing practice of providing one when Proposition 98 funds are available. The COLA rate is based on a price index published by the federal government that reflects changes in the cost of goods and services purchased by state and local governments across the country.

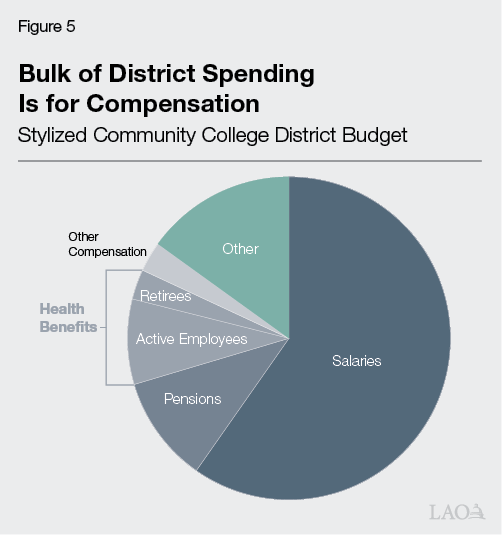

Compensation Is Largest District Operating Cost. Figure 5 shows a stylized community college district budget. The largest component of a district’s budget is spent on salaries. Together, all compensation and compensation‑related costs—including salaries, retirement, health care benefits, workers compensation, and unemployment insurance—typically account for 80 percent to 85 percent of a district’s budget. The remainder of a district’s budget is for various other core operating costs, including utilities, insurance, software licenses, equipment, and supplies.

Staffing Levels Have Declined, Particularly Among Part‑Time Faculty. From fall 2019 to fall 2021, the total number of CCC employees (headcount) declined by 8 percent, from 93,000 to 85,000. Part‑time faculty—which historically have made up nearly half of CCC employees—experienced the largest decline (12 percent). This decline was due to districts offering fewer course sections as a result of lower enrollment. (When districts reduce course sections, they typically reduce their use of part‑time faculty, who are hired as temporary employees, compared to full‑time faculty, who are hired as permanent employees.) Other CCC staff (such as classified staff) declined by 5 percent between 2019 and 2021, likely due to a combination of districts eliminating positions due to workload reductions and an inability to fill vacancies. District administrators indicate that vacancies have increased over the past couple of years as a result of a tighter labor market. Across the state, most districts have experienced staffing reductions, thereby generating associated savings.

Systemwide Reserves Continue to Increase. District unrestricted reserves have increased each year of the pandemic. Whereas unrestricted reserves totaled $1.8 billion (22 percent of expenditures) in 2018‑19, they have grown to an estimated $2.7 billion (32 percent of expenditures) in 2021‑22. This is nearly double the Government Finance Officers Association’s and Chancellor’s Office’s recommendation that unrestricted reserves comprise a minimum of 16.7 percent (two months) of expenditures. The increase in reserves is the result of several factors, including savings from using fewer part‑time faculty and staff vacancies. Also, colleges’ receipt of federal relief funds and other COVID‑19‑related funds during this time reduced pressure on local and state funds to cover technology and certain other costs.

Proposal

Governor Proposes Apportionment COLA. The Governor’s budget includes $653 million to cover an 8.13 percent COLA for apportionments. This is the same COLA rate the Governor proposes for the K‑12 Local Control Funding Formula.

Assessment

Districts Likely to Feel Salary Pressure in 2023‑24. Over the past year, both inflation and wage growth (across the nation and in California) have been at their highest levels in several decades. Elevated inflation and broad‑based wage growth are expected to continue in 2023‑24. Community college districts, in turn, are likely to feel pressure to provide their employees with salary increases. We estimate every 1 percent increase in CCC’s salary pool would cost approximately $70 million.

Districts’ Other Core Operating Costs Also Are Likely to Increase. Districts’ pension costs are expected to increase, albeit modestly compared with recent years. Based on current assumptions, the district contribution rate to the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS) stays constant at 19.1 percent in 2023‑24, while the district contribution rate to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) increases from 25.4 percent to 27 percent. (About half of CCC employees participate in CalSTRS, with the other half participating in CalPERS.) Community college pension costs are expected to increase by about $73 million in 2023‑24. (Unlike in some recent years, the Governor does not have proposals addressing unfunded retirement liabilities or providing district pension relief.) Similar to the other education segments, community college districts generally also expect to see higher costs in 2023‑24 for health care premiums, insurance, equipment, supplies, and utilities.

State Likely Has Limited Capacity to Fund a Higher COLA. Since the Governor’s budget was released, the state has received updated data used to calculate the COLA rate. Based upon the new data, the estimated COLA rate is somewhat higher (8.40 percent). The COLA rate will be finalized in late April when the federal government releases the last round of data used in the calculation. Though the final rate likely will be even higher than the 8.13 percent COLA rate proposed in January, we are concerned with the state’s ability to sustain a higher rate. As we discuss in more detail in The 2023‑24 Budget: Proposition 98 Overview and K‑12 Spending Plan, we estimate the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee for 2023‑24 could be lower than the January budget level due to expected downward adjustments in General Fund revenues. If this were to be the case, the revised minimum guarantee might be unable support even the COLA rate proposed in January, making a higher May COLA rate further out of reach. Growth in the minimum guarantee also might be unable to support the full statutory COLA rates over the subsequent few years.

Per‑Student Funding Is Much Higher Today Than Before the Pandemic. We believe most community college districts likely could manage a smaller apportionment COLA without notable fiscal difficulty. Not only are staffing levels down, along with accompanying staffing costs, but budgeted per‑student Proposition 98 funding is at an all‑time high. In 2018‑19 (the year before the pandemic), community college per‑student funding also was at an all‑time high. Under the Governor’s budget, per‑student funding would be approximately $700, or nearly 7 percent higher than that pre‑pandemic level after adjusting for inflation. Moreover, actual funding per student is significantly above budgeted funding per student. Though enrollment has dropped since 2018‑19, funding has not been adjusted accordingly. Rather, a series of hold‑harmless provisions has insulated community colleges from the fiscal impact of enrollment declines. We estimate current actual funding per student is approximately $3,000 (30 percent) higher than pre‑pandemic levels after adjusting for inflation.

Recommendation

Consider 8.13 Percent Apportionment COLA Rate an Upper Bound. By the May Revision, the Legislature will have updated information on a number of key factors, including General Fund revenues, the Proposition 98 minimum guarantee, and the statutory COLA rate. Based on these updated data, the Legislature will be able to finalize its apportionment COLA decision. Given the downside risks over the coming months, the Legislature could treat the 8.13 percent COLA rate as an upper bound in 2023‑24. Were the estimate of the 2023‑24 minimum guarantee to be significantly lower at the May Revision, however, the Legislature may wish to consider a lower rate than 8.13 percent. For planning purposes, each 0.5 percentage point reduction in the COLA rate would reduce apportionment costs by approximately $40 million. (In addition to the risk of General Fund revenue and the minimum guarantee being revised downward, the amount available for an apportionment COLA could depend on the issue discussed below—a potential shortfall in the Governor’s budget relating to the apportionment formula.)

SCFF Funding Protections

In this section, we first provide background on the CCC apportionment formula and certain funding protections, including a protection known as “stability funding.” We then describe how the administration and Chancellor’s Office currently are interpreting the stability funding provision and identify resulting differences in the estimated cost to fund CCC apportionments in 2023‑24. Next, we provide an assessment of the situation and offer associated recommendations.

Apportionment Formula

State Adopted New Apportionment Funding Formula in 2018‑19. For many decades, the state allocated general purpose funding to community colleges based almost entirely on their enrollment. Districts generally received an equal per‑student funding rate. Student funding rates were not adjusted according to the type of student served or whether students ultimately completed their educational goals. In 2018‑19, the state moved away from that funding model. In creating SCFF, the state placed less emphasis on seat time and more emphasis on students achieving positive outcomes. The new funding formula also recognized the additional cost that colleges have in serving students who face higher barriers to success (due to income level or other factors). Another related objective was to provide a strong incentive for colleges to enroll low‑income students and ensure they obtain financial aid to support their educational costs.

Apportionment Formula Has Three Main Components. The components are: (1) a base allocation linked to enrollment, (2) a supplemental allocation linked to low‑income student counts, and (3) a student success allocation linked to specified student outcomes. For each of the three components, the state set funding rates. In any year in which the state provides a COLA, each of these funding rates increases accordingly, such that the total resulting SCFF‑generated apportionment amount effectively has COLA changes embedded within it. The supplemental and student success components of the formula do not apply to incarcerated students, dually enrolled high school students, or students in noncredit programs. Apportionments for those students remain based entirely on enrollment. (“Basic aid” or “fully community‑supported” districts receive revenue from local property taxes and enrollment fees that exceed what they generate under SCFF, such that the SCFF calculation does not affect their apportionment funding.) We next describe each of the three main components of the apportionment formula in more detail.

Base Allocation. As with the prior apportionment formula, the base allocation of SCFF gives a district certain amounts for each of its colleges and state‑approved centers, in recognition of the fixed costs entailed in running an institution. On top of that allotment, a district receives funding for each FTE student it enrolls ($4,840 in 2022‑23 for the regular credit rate). Most FTE student counts (approximately 85 percent) are based on a three‑year rolling average. The rolling average is based on a district’s FTE count that year and the prior two years. (For example, the 2018‑19 calculation was based on a district’s FTE count for 2018‑19, 2017‑18, and 2016‑17.) Using a rolling average is intended to smooth annual adjustments to a district’s apportionment funding. By comparison, remaining student counts (approximately 15 percent) are based on an FTE count that year. (For example, the 2018‑19 calculation was based on 2018‑19 FTE counts.) This counting method applies to incarcerated students, dually enrolled high school students, and students in noncredit programs.

Supplemental Allocation. SCFF provides an additional amount (about $1,145 in 2022‑23) for every student who receives a Pell Grant, receives a need‑based fee waiver, or is undocumented and qualifies for resident tuition. Student counts are “duplicated,” such that districts receive twice as much supplemental funding (about $2,290 in 2022‑23) for a student who is included in two of these categories (for example, receiving both a Pell Grant and a need‑based fee waiver). The allocation is based on student counts from the prior year.

Student Success Allocation. The formula also provides additional funding for each student achieving specified outcomes, including obtaining various degrees and certificates, completing transfer‑level math and English within the student’s first year, and obtaining a regional living wage within a year of completing community college. (For example, a district generates about $2,700 in 2022‑23 for each of its students receiving an associate degree for transfer. The formula counts only the highest award earned by a student.) Districts receive higher funding rates for the outcomes of students who receive a Pell Grant or need‑based fee waiver, with somewhat greater funding rates for the outcomes of Pell Grant recipients. The student success component of the formula is based on a three‑year rolling average of student outcomes. The rolling average is based on outcomes data from the prior year and two preceding years. As with the base allocation, the objective of using a three‑year rolling average for this component of SCFF is to smooth associated annual funding adjustments.

Funding Protections

Statute Has Several Funding Protections for Districts. These protections allow districts to earn more in apportionment funding than they would otherwise earn through the formula’s regular calculations and funding rates. The next three paragraphs describe these special protections.

“Emergency Conditions Allowance” Protects Districts From Unexpected Enrollment Declines Due to Natural Disasters and Other Extraordinary Situations. While statute specifies the years of data that are to be used to calculate each component of SCFF, state regulations provide the Chancellor’s Office with authority to use alternative years of enrollment data in extraordinary cases. This funding protection is commonly known as the emergency conditions allowance. The Chancellor’s Office typically invokes this authority in response to a single district experiencing an unexpected enrollment decline resulting from a disaster or other emergency (for example, due to a wildfire affecting the ability of a college to remain open). From 2019‑20 through 2022‑23, however, the Chancellor’s Office applied the protection to all districts. Specifically, it allowed all districts to use pre‑pandemic enrollment data to calculate how much they generate from SCFF. Under this protection, districts could use pre‑pandemic data for all their student enrollment counts—regular credit counts as well as counts for incarcerated students, dually enrolled high school districts, and noncredit students.

Pandemic‑Related Emergency Conditions Allowance Set to End. In late spring 2022, the Chancellor’s Office notified districts that 2022‑23 will be the final year of the pandemic‑related emergency conditions allowance. For their credit student counts in 2023‑24, districts will use pre‑pandemic data for two years of the three‑year rolling average calculation, along with 2023‑24 data for the third year of the calculation. For incarcerated students, dually enrolled high school students, and noncredit students, districts will use 2023‑24 data. Four districts will be able to continue claiming emergency conditions allowances in 2023‑24 for other extraordinary situations, such as from enrollment losses resulting from wildfires.

Statute Provides “Hold Harmless” Funding Protection. The apportionment funding formula also includes a provision for those districts that would have received more funding under the former apportionment formula. The intent of the hold harmless protection is to provide time for those districts to ramp down their budgets to the new SCFF‑calculated funding level or find ways to increase the amount they generate through SCFF (such as by enrolling more financially needy students or improving student outcomes). Through 2024‑25, districts funded according to the hold harmless provision receive whatever they generated in 2017‑18 under the old formula, plus any subsequent apportionment COLA provided by the state.

Stability Funding Provides Another Form of Protection for Districts. As administered by the Chancellor’s Office, this protection allows a district to receive in a given year the greater of the amount generated by the SCFF formula in that year or the prior year adjusted for any apportionment COLA funded by the state. Given ambiguity in the associated statutory provision, the Department of Finance (DOF) has a different way of viewing stability funding. Under the DOF approach, only districts whose amount generated by the SCFF formula declines in a given year compared to the previous year’s SCFF‑calculated amount is eligible for stability. We discuss these differences more later in this section.

Statute Permits Districts to Receive Whichever Method Yields the Highest Apportionment Amount. Each year, the Chancellor’s Office calculates the amount each district generates through (1) the SCFF calculation (using the emergency conditions allowance’s alternative enrollment years, if a district has that protection), (2) hold harmless, and (3) stability. Assuming enough funding is available for apportionments, each district receives the highest of those three amounts.

Stability Funding

Under Old Apportionment Formula, Stability Protection Was Based on Enrollment. Statute has long provided districts with protection from sudden enrollment declines. Prior to adoption of SCFF, the stability protection was linked directly to declining enrollment. State law allowed declining‑enrollment districts to retain enrollment funding for vacant slots in the year they became vacant in order to cushion district budgets from immediate funding losses. Districts lost enrollment funds, however, for slots that remained vacant for a second year. Stability protection effectively allowed declining‑enrollment districts to have their apportionment funding rachet down on a one‑year lagged basis, thereby giving districts time to adjust their budgets.

SCFF Statute Modified Stability Provision. Instead of providing stability based on enrollment as under the old formula, current law provides stability protection based on districts’ total apportionment funding. As stated in 2019‑20 budget trailer legislation, “Commencing with the 2020‑21 fiscal year, decreases in a community college district’s total revenue computed [using SCFF’s calculations] shall result in the associated reduction beginning in the year following the initial year of decreases.” In the next year, 2020‑21 budget trailer legislation added the phrase, “[as] adjusted for changes in the cost‑of‑living adjustment.”

Administration Interprets Stability Provision One Way… The administration applies the stability provision only to districts whose funding generated by the SCFF calculation declines in a given year compared to the previous year. In such a case, the administration provides those districts with their prior‑year SCFF amount plus any COLA provided by the state in the current year. For example, a district that generated $100 million under the SCFF calculation in 2021‑22 but only $90 million under the SCFF calculations in 2022‑23 would receive $105 million in 2022‑23 assuming a 5 percent COLA that year.

…With the Chancellor’s Office Interpreting the Stability Provision Differently. In contrast, the Chancellor’s Office considers any district eligible for stability funding even if it does not decline from year to year. For example, a district that generates $100 million under the SCFF calculation in 2021‑22 and $102 million under the SCFF calculation in 2022‑23 would be eligible to receive $105 million in 2022‑23 assuming a 5 percent COLA that year. Under the Governor’s interpretation, that same district would receive $102 million in 2022‑23 (that is, no stability funding) because the amount it generated under the SCFF calculations did not decline compared to its 2021‑22 amount.

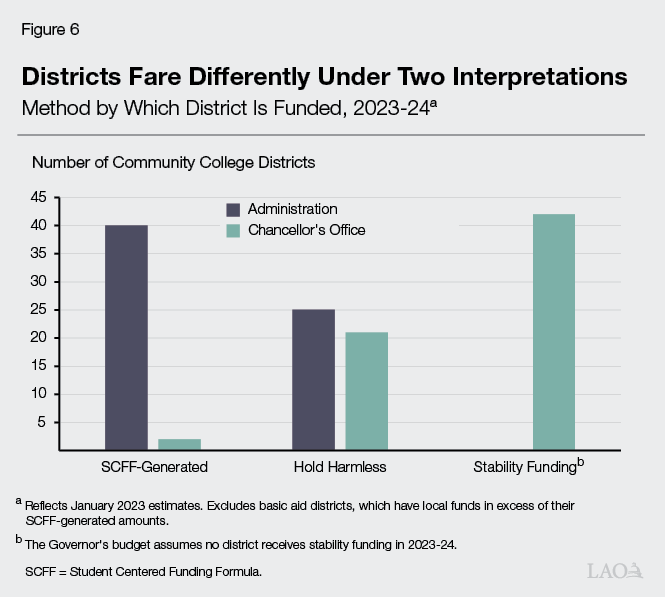

Different Interpretations Lead to Different Cost Estimates. As Figure 6 shows, no districts receive stability funding under DOF’s interpretation, with many districts (40) funded based on the SCFF calculation. By comparison, under the interpretation of the Chancellor’s Office, 42 districts receive stability funding and only 2 are funded based on the SCFF calculation. From a cost perspective, DOF accordingly budgets nothing for the stability provision, whereas the Chancellor’s Office estimates the stability provision costs $145 million in 2023‑24. Under the Chancellor’s Office approach, costs are so much higher because the expiration of the emergency conditions allowance results in 2023‑24 SCFF amounts being lower for most districts than their 2022‑23 SCFF funding levels adjusted by COLA.

Actual Cost Differences Will Depend on Various Factors in Current and Budget Year. DOF built its most recent apportionment model in late fall 2022. The model relies on numerous assumptions about how much each district will generate under SCFF in 2022‑23 and 2023‑24. The Chancellor’s Office will release preliminary estimates of enrollment, supplemental, and student success allocations in late February 2023. Based on those estimates, along with the COLA rate the state ends up providing and what districts end up generating under the SCFF calculation in 2023‑24, the actual cost to fund apportionments in the budget year could be higher or lower.

Assessment

Stability Provision Is Unclear. As currently written, statute describing the stability provision and when it is applied to districts is confusing and difficult to understand. Statute does not clearly identify declines relative to a specified baseline year or explain how to apply a COLA.

Using Administration’s Interpretation Would Create Irrational Funding Outcomes. Though statute is not wholly clear, the administration’s interpretation of the stability provision appears to be closer to the letter of law. Statute references “decreases” in funding levels. The administration’s interpretation also is closer to how stability was applied under the old apportionment formula. Yet, if the administration’s interpretation were followed as state policy, some districts would get more than others for unjustified reasons. For example, a district whose amount generated by SCFF declined by even $1 in a given year compared to the prior year would receive the prior‑year amount plus any COLA that is provided. Another district whose amount generated by SCFF increased by as little as $1 would only receive the current‑year amount. As a result, districts with nearly identical levels generated under the SCFF calculation could receive considerably different apportionment funding amounts.

Chancellor’s Office’s Interpretation Lacks Policy Justification. Though the Chancellor’s Office’s interpretation does not result in the same irrational outcomes as the administration’s interpretation, it does provide more funding to a district than may be justified. If long‑standing state policy serves as a guide, stability was created to help cushion districts in the event their enrollment or other components of SCFF resulted in less funding in a given year. Under the way the Chancellor’s Office administers stability, even districts whose SCFF‑calculated funding increases over the prior year receive stability funding.

Recommendations

Recommend Legislature Clarify Statutory Provision. Differing interpretations of the stability funding provision is creating problems both for districts in understanding how much apportionment funding they will receive and for the Legislature in knowing how much funding to budget for apportionment costs. We recommend the Legislature modify statute to clarify the intent of stability funding and how it is to be calculated.

Recommend Legislature Make Stability Funding Provision Consistent With Long‑Standing State Policy. Specifically, we recommend the Legislature clarify that the intent of stability funding is to help cushion districts from losses in funding due to unexpected events. Furthermore, we recommend the Legislature specify that the calculation of stability funding be based on the higher of districts’ SCFF‑generated amount that year or the previous year. Under our recommendation, only districts that would otherwise experience a decline in their SCFF funding would receive stability funding. Their stability allotment would equal the difference between their lower SCFF amount that year (accounting for any COLA provided that year) and the higher amount they received through SCFF the previous year (accounting for any COLA provided the previous year). For example, if a declining‑enrollment district generated $100 million from SCFF in a given year, then generated $99 million from SCFF the next year, it would receive apportionment funding of $100 million (the higher of the two years). In this example, the cost of the stability provision is $1 million (the difference in funding between the two years). This approach avoids the irrational outcomes that emerge under the administration’s method while also avoiding giving districts with declining enrollment or other SCFF factors funding above their prior‑year allocations, as happens under the Chancellor’s Office’s method. Our recommendation avoids those outcomes but still serves the core policy objective of providing a budget cushion for affected districts.

Consider Options for 2023‑24. The Legislature could adopt our recommended new definition of stability and have it take effect beginning in 2023‑24. Districts, however, already are preparing their 2023‑24 budgets assuming they receive stability as interpreted by the Chancellor’s Office. Were the Legislature to decide to fund stability in the budget year consistent with the Chancellor’s Office’s interpretation, the estimated apportionment cost would be $134 million more than the Governor’s January proposal. (Under the Chancellor’s Office’s interpretation, stability funding costs are $145 million higher, but hold harmless costs are $11 million lower than the administration’s estimates.) Unless it could find new funds in the state budget, the Legislature would need to repurpose existing Proposition 98 funds to address this shortfall (such as by reducing the apportionment COLA rate for all districts in the budget year). By the time of the May Revision, the Legislature will have better estimates on 2022‑23 enrollment and funding levels under the SCFF calculation. This data will assist the Legislature in refining its estimate of the shortfall and deciding how to treat stability in the budget year.

Facilities Maintenance

In this section, we first provide background on CCC facilities, maintenance backlog, and the maintenance categorical program. We then describe the Governor’s proposals to reduce funding for the CCC maintenance categorical program and add trailer bill language allowing community colleges to use their maintenance categorical funds on campus child care facilities. Next, we assess those proposals and offer associated recommendations.

Background

Districts Have Many Facilities and Associated Infrastructure. Collectively, the state’s 72 community college districts have 6,000 buildings with 87 million square feet of associated academic space. In addition to academic facilities, districts have a notable amount of campus infrastructure such as central plants and utility distribution systems. Districts also have self‑supporting facilities such as parking structures and student unions. These latter types of facilities typically generate their own fee revenue, which covers associated capital and operating costs. Depending on how a district uses them, certain types of district buildings such as an auditorium may be considered academic, nonacademic, or dual purpose. An auditorium may be considered academic, for example, if CCC students use the facility as part of their instructional program (such as a performing arts department). It may be considered nonacademic and self‑supporting if used entirely for community purposes.

CCC Maintains Inventory of Facility Conditions. Community college districts jointly developed a set of web‑based project planning and management tools called FUSION (Facilities Utilization, Space Inventory Options Net) in 2002. The Foundation for California Community Colleges (the Foundation) operates and maintains FUSION on behalf of districts. The Foundation employs assessors to complete a facility condition assessment of buildings at districts’ campuses on a three‑ to four‑year cycle. These assessments, together with other facility information entered into FUSION, provide data on CCC facilities and help districts with their local planning efforts.

State Has a Categorical Program for Maintenance and Repairs. Known as “Physical Plant and Instructional Support,” this program allows districts to use funds for facilities maintenance and repairs, the replacement of instruction‑related equipment (such as desks) and library materials, hazardous substances abatement, and water conservation projects, among other related purposes. Community college regulations prohibit districts from using categorical program funds for parking garages, student centers, and certain other self‑supporting facilities. Within these statutory parameters, districts have flexibility on how to use their categorical funds, but historically they have used about 75 percent for deferred maintenance and related facilities projects, with the remaining 25 percent being used for instructional equipment and library materials. To use this categorical funding for maintenance and repairs, districts must adopt and submit to the CCC Chancellor’s Office through FUSION a list of maintenance projects, with estimated costs, that the district would like to undertake over the next five years. In addition to these categorical funds, CCC districts fund maintenance from their apportionments and other district operating funds (for less expensive projects) and from state and local bond funds (for more expensive projects).

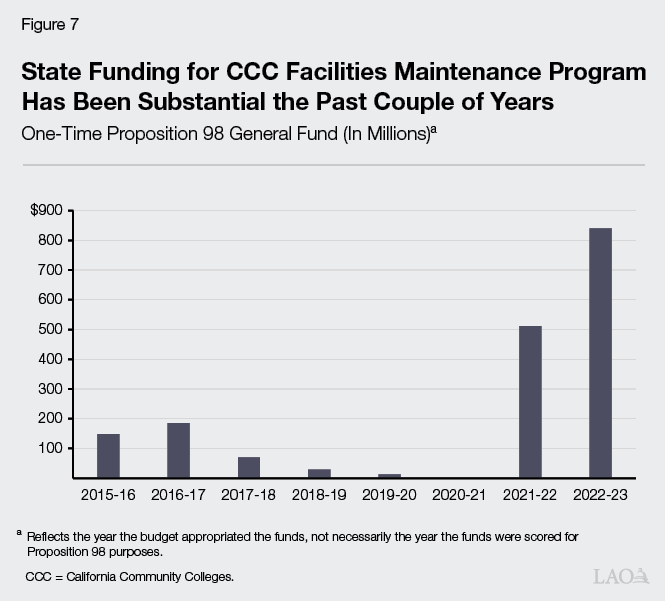

State Has Provided Substantial Funding for Categorical Program Over Past Several Years. Historically, the Physical Plant and Instructional Support categorical program has received appropriations when one‑time Proposition 98 funding is available and no appropriations in tight budget years. Since 2015‑16, the Legislature has provided a total of $1.8 billion for the program. As Figure 7 shows, the largest appropriation came from the 2022‑23 budget, which provided $841 million. Districts have until June 2027 to spend these funds. Based on reporting by districts in late fall 2022, districts plan to spend about 75 percent ($630 million) of their 2022‑23 funds on various deferred maintenance and related facilities projects, with the remaining funds spent on instructional equipment and library materials.

With Recent Funding, Maintenance Backlog Expected to Shrink Significantly. Entering 2021‑22, the Chancellor’s Office reported a systemwide deferred maintenance backlog of about $1.6 billion. The Chancellor’s Office has not provided an update on the size of the backlog based on the last two years of funding (plus local spending on projects). We estimate, however, that the backlog has been reduced to roughly $700 million.

Proposal

Reduces 2022‑23 Budget Allocation for Physical Plant and Instructional Support Program by $213 Million. Funding for the program would decrease from $841 million to $628 million. The administration indicates that the resulting savings would be used to fund the Governor’s enrollment and retention strategies proposal (discussed in the “Enrollment” section of this brief).

Adds Child Care Facilities as Allowable Use of Maintenance Categorical Program Funds. Proposed trailer bill language gives campuses the option to use Physical Plant and Instructional Support funds for “child care facility repair and maintenance.” Current law is silent on this issue. Both DOF and the CCC Chancellor’s Office assert that nothing in statute or community college regulations currently precludes districts from using categorical programs funds for this purpose. No prohibition exists either for child care centers that also are used for academic purposes (as part of a laboratory whereby CCC child development students observe and interact with children, for example) or for child care purposes only. (As of this writing, the Chancellor’s Office has not confirmed the number of child care centers of either type but indicates most currently serve a dual purpose.) By specifying child care centers in statute, DOF has indicated it intends to signal the administration’s support for community college districts using state funds for this type of facility.

Assessment

Reducing Deferred Maintenance Funding Would Disrupt District Plans and Increase Backlog. As of January 2023, the Chancellor’s Office indicates it has disbursed $504 million of the $841 million in 2022‑23 funds. The Chancellor’s Office is scheduled to disburse the remaining $337 million to districts by June 2023. As discussed above, districts have already identified and planned how they intend to spend their 2022‑23 funds. In some cases, districts indicate they have collected bids on projects. Though all categorical program funds likely would not be spent in 2022‑23, they would be spent over the coming years. By reducing funding for this purpose, the deferred maintenance backlog will be larger than otherwise. Addressing deferred maintenance is important because it can help avoid more expensive facility projects, including emergency repairs, in the long run.

Unclear Rationale for Allowing Districts to Fund Nonacademic Facilities. Under the Governor’s trailer bill proposal, community colleges could use state funds for maintenance projects at all campus child care centers, even those that do not operate academic programs on behalf of the college. Such a policy conflicts with standard higher education facility policy. Typically, the state does not subsidize nonacademic, self‑supporting programs. The fees these programs charge are intended to cover their operations and facilities maintenance costs.

Dual‑Purpose Centers Raise a Few Key Issues. Those child care centers that do operate academic programs on behalf of the college still collect fees from the clients using those centers. For other child care centers located throughout the state, these fees would be expected to cover the operations and maintenance of their facilities. Classifying campus child care centers as academic facilities and using state CCC funds for their maintenance thus would provide them with special treatment over other child care centers in the state. The state, however, might want to provide this advantage to campus centers given the academic benefits they provide to the college. The state, alternatively, might want to share facility costs with the campus centers, thereby still providing them with an advantage, but a smaller advantage, over other child care centers in the state.

Recommendation

Reject Proposal to Reduce Funding for Facilities Maintenance. For the reasons stated above, we recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal to reduce funding for the Physical Plant and Instructional Support program by $213 million Proposition 98 General Fund. (Proposition 98 funds must be spent on a Proposition 98 purpose, such that they are not available to help the state address a non‑Proposition 98 budget shortfall.) As discussed in the “Enrollment” section of this brief, we also recommend the Legislature reject the Governor’s proposal effectively to redirect these facilities funds to a student outreach initiative.

Modify Proposed Language to Fund Only Certain Child Care Facilities. We recommend the Legislature modify the Governor’s proposal by clarifying in statute that districts may use categorical program funds for child care centers that also serve an academic purpose. Moving forward, though, the Legislature may want to establish a cost‑sharing expectation for these dual‑purpose centers, in which fees cover at least a portion of facilities costs. Lastly, we recommend prohibiting districts from using such funds for nonacademic, self‑supporting child care centers. The state makes this key distinction for other higher education facility programs.