This is the fourth blog post in our series California’s Property Tax: Where Does Your Money Go? This post explains the primary factors affecting a city’s “proportion of the property tax.” We define a city’s proportion of the property tax as the property taxes the city receives relative to the total property taxes collected from the 1 percent tax within its boundaries. For example, if the total property tax revenue collected from the 1 percent tax within a city was $1 million and the city received $200,000 in revenue from the 1 percent tax, we would say this city receives 20 percent of the property tax collected within its boundaries. (Note: A city’s proportion of the property tax is distinct from its "AB 8 allocation." Future blog posts will discuss the allocation process prescribed under AB 8.)

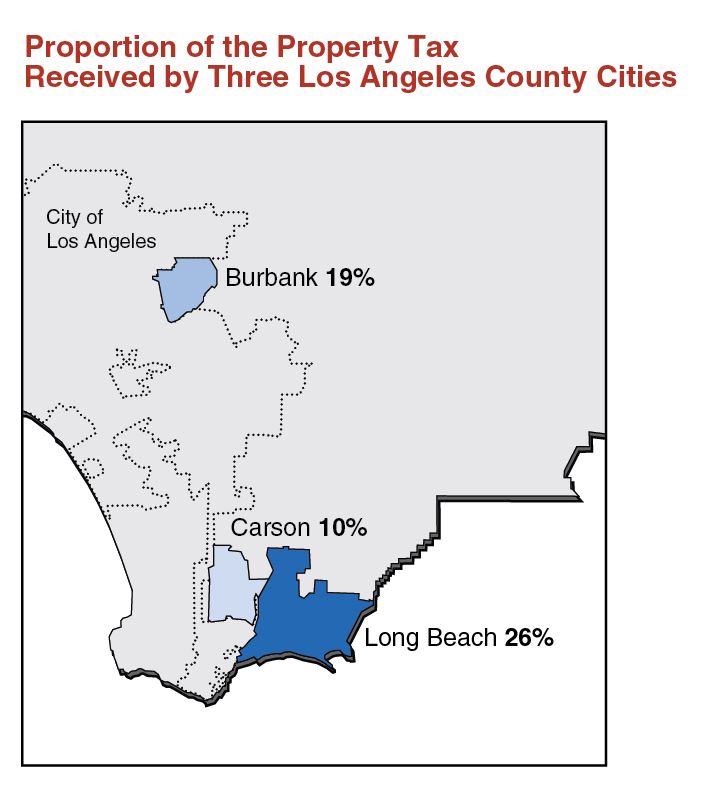

Statewide, cities’ proportion of the property tax varies widely. The statewide average is roughly 20 percent, but in Los Angeles County alone, cities’ proportions of the property tax range from less than 10 percent to over 30 percent. There are four primary factors affecting a city’s proportion of the property tax: (1) historical property tax revenue, (2) the vehicle license fee swap, (3) redevelopment, and (4) property tax revenue from the county. We discuss these four factors below using three cities in Los Angeles County (shown below) as examples.

Historical Property Tax Revenue Has the Largest Impact on the Property Taxes Cities Receive Today. When the steps for distributing the 1 percent tax first were established in the late 1970s, the amount of property taxes cities received—compared to other local governments serving the same area—became the starting point for determining the amount of property tax cities would receive moving forward. In many cases, the property tax revenue a city received in the mid-1970s reflected the services the city directly provided compared to other local governments serving the same area. Often, this continues to be true today. For example, today, Long Beach receives 26 percent of the property taxes collected within its boundaries. Long Beach is a full-service city, responsible for all municipal services for its residents. In contrast, Carson, which is responsible for only some municipal services for its residents, receives only 10 percent.

The services a city provides does not fully explain its proportion of the 1 percent tax, however. Burbank—also a full-service city—receives 19 percent of the property taxes collected within its boundaries. This is seven percent less than Long Beach, despite both cities being full service. Much of the difference between the two cities’ proportions results from their property tax starting points. As mentioned above, cities’ property tax revenue is primarily based on what each city received compared to the other local governments in its area in the mid-1970s. Thus, Burbank receives a lower proportion of property tax than Long Beach because in the mid-1970s Burbank received less property tax revenue compared to the local governments in its area than Long Beach received compared to its other local governments.

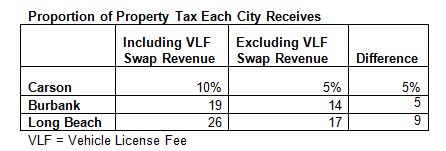

Vehicle License Fee (VLF) Swap Increases Cities’ Property Taxes. Since lowering the VLF rate in the mid-1990s, the state has reimbursed counties and cities for their lost revenue. Before 2004, the state provided counties and cities state General Fund revenue to reimburse these losses. Starting in 2004, the state paid for the lost VLF revenue by redirecting a portion of property taxes from schools to counties and cities. This was called the VLF swap. The amount counties and cities received was based on their populations. Today, counties’ and cities’ VLF swap amounts increase annually based on growth in the assessed value of property within their boundaries. (Note: Year-to-year growth in the VLF swap differs from the growth described in Step 2 of our earlier video.) As a result of the VLF swap, counties and cities receive a larger proportion of the 1 percent tax than they received before the swap. As shown below, the proportions of the property tax Carson, Burbank, and Long Beach receive all increase as result of the VLF swap.

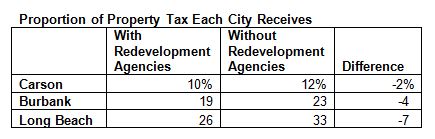

Large Redevelopment Agencies Reduce Cities’ Property Tax Revenue. Historically, cities and counties established redevelopment agencies to reduce urban blight. Redevelopment agencies used revenue growth from the 1 percent tax to finance their projects. As a result, cities with redevelopment agencies received less property tax revenue, reducing the proportion of the property tax these cities received. Had these cities not established redevelopment agencies, they would have received higher proportions of the property tax. As shown below, Long Beach—which had a large redevelopment agency—sees the greatest reduction in its proportion of the property tax due to redevelopment.

“No and Low” Cities Receive Additional Property Tax Revenue From Their Counties. Carson is one of roughly 90 cities that did not receive or received very little property tax revenue in the mid-1970s. In fact, about 30 of these 90 cities (including Carson) received no property tax at all in the mid-1970s. These cities relied more heavily on other types of revenue like sales tax and business licensing fees. As a result, these cities received “no or low” proportions of the 1 percent tax when it was established in the late 1970s. In the late 1980s, the state guaranteed these “no and low” cities a minimum proportion of the property tax. To do this, the state required each county to shift a portion of its 1 percent tax revenue to any cities within the county that received less than 7 percent of the property taxes collected within the cities’ boundaries. As a result, today, these “no and low” cities receive more property tax revenue than they would have received without this state guarantee.

To receive email notices of future posts in this series, email the LAO's local government analyst, Carolyn Chu.

Follow @LAOEconTax on Twitter for regular California economy and tax updates.