LAO Contact

Appendix Tables:

Discretionary Spending Proposals

Update (5/20/22): Updated to reflect information about state appropriations limit (SAL) excluded spending and other budget proposals.

May 16, 2022

The 2022-23 Budget

Initial Comments on the

Governor’s May Revision

- Introduction

- Budget Condition

- The Surplus

- The State Appropriations Limit

- Budget Structure Comments

- Surplus Allocation Considerations

- Appendix Tables: Discretionary Spending Proposals

Key Takeaways

Governor Allocates $52 Billion Overall General Fund Surplus in May Revision. Reflecting extraordinary revenue growth for a second year in a row, we estimate the Governor had a $52 billion General Fund surplus to allocate in the May Revision. In addition, under the administration’s revenue estimates, the Governor had a $33.5 billion surplus within the school and community college budget to allocate to discretionary purposes. Across these two surpluses, the Governor allocates $40 billion to meet the state’s constitutional requirements under the state appropriations limit (SAL). The largest categories of spending from the overall General Fund surplus are for natural resources and transportation programs.

May Revision Sets Up Fiscal Cliff for 2023‑24. While the administration meets the SAL requirements across the prior and current year, the Governor leaves $3.4 billion in unaddressed SAL requirements in 2022‑23. Moreover, we estimate the state would face an additional SAL requirement of over $20 billion in 2023‑24. The Governor’s May Revision does not have a plan to address this roughly $25 billion requirement. As a result, the state would very likely face a significant budget problem next year, which could require reductions to programs.

Recession Risk Heightened. Predicting precisely when the next recession will occur is not possible. However, certain economic indicators historically have offered warning signs that a recession is on the horizon. Many of these indicators currently suggest a heightened risk of a recession within two years.

Recommend Increasing Reserves. We strongly recommend the Legislature consider building more reserves than proposed by the Governor in the May Revision. Additional reserves can help the state address either future SAL requirements or a budget problem resulting from a recession. We recommend taking a fiscally prudent approach, which would be to identify several billion dollars in non‑excluded spending and instead dedicate those funds to reserves.

Introduction

On May 13, 2022, Governor Newsom presented a revised state budget proposal to the Legislature. (This annual proposed revised budget is called the “May Revision.”) In this brief, we provide a summary of the Governor’s revised budget, focusing on the overall condition and structure of the state General Fund—the budget’s main operating account. In the coming days, we will analyze the plan in more detail and provide additional comments in hearing testimony and online. The information presented in this brief is based on our best understanding of the administration’s proposals as of 11:00 AM, May 14, 2022. In many areas of the budget, this understanding will continue to evolve as we receive more information. We only plan to update this brief for very significant changes (that is, those greater than $500 million).

Budget Condition

Figure 1 shows the General Fund condition based on the Governor’s proposals and using the administration’s estimates and assumptions.

Figure 1

General Fund Condition Summary

(In Millions)

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

|

|

Prior‑year fund balance |

$5,889 |

$37,699 |

$15,425 |

|

Revenues and transfers |

194,575 |

226,956 |

219,632 |

|

Expenditures |

162,765 |

249,229 |

227,364 |

|

Ending fund balance |

$37,699 |

$15,425 |

$7,694 |

|

Encumbrances |

$4,276 |

$4,276 |

$4,276 |

|

SFEU balance |

$33,423 |

$11,149 |

$3,418 |

|

Reserves |

|||

|

BSA |

$14,643 |

$20,325 |

$23,283 |

|

SFEU |

33,423 |

11,149 |

3,418 |

|

Safety net |

900 |

900 |

900 |

|

Total Reserves |

$48,966 |

$32,374 |

$27,601 |

|

SFEU = Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties and BSA = Budget Stabilization Account. |

|||

Changes in Budget Condition Since Governor’s Budget

Revenues Higher by Nearly $57 Billion Compared to Governor’s Budget. Revenue growth over the last two years has been extraordinary. Following growth of nearly 30 percent in 2020‑21, revenues are projected to grow by almost 20 percent in 2021‑22. Reflecting these unprecedented collections, the May Revision assumes revenues (excluding Budget Stabilization Account [BSA] transfers) will be $57 billion higher than the Governor’s budget over the budget window. Our office’s revenue estimates are very similar to these estimates (only about $450 million higher over the budget window).

Constitutional Requirements Higher by $23 Billion. The State Constitution has three major voter initiatives that require the Legislature to spend some revenues in specific ways. Specifically, Proposition 4 (1979) constrains how the state can spend revenues that exceed a specific threshold; Proposition 98 (1988) requires the state to allocate a certain share of revenues for spending on schools and community colleges; and Proposition 2 (2014) requires the state to set aside some revenues—particularly capital gains revenues—to build reserves, pay down state debts, and in some cases, spend more on infrastructure. Reflecting the higher revenue estimates, and including policy changes, the May Revision reflects higher constitutionally required spending on K‑14 education of $21 billion across the budget window. In addition, Proposition 2 reserve requirements are higher by $2.4 billion while debt payments are lower by $500 million due to changes in the components of estimated revenues. (We discuss Proposition 4, and its impact on the surplus, in a subsequent section.)

Baseline Spending Higher by $11 Billion. Across the rest of the budget, other baseline costs are higher by $11 billion. This is primarily the result of early legislative action, including adopting $5.7 billion in a variety of revenue reductions—such as the restoration of net operating loss deductions—and $2.7 billion for rental assistance.

Reserves Under Governor’s May Revision

General Purpose Reserves Reach Nearly $28 Billion. The bottom of Figure 1 shows general purpose reserves planned for the end of 2022‑23 under the administration’s estimates and assumptions. Under the Governor’s May Revision, the state would end 2022‑23 with $27.6 billion in general purpose reserves. This total includes $23.3 billion in the BSA, the state’s main constitutional reserve governed by Proposition 2; $3.4 billion in the Special Fund for Economic Uncertainties (SFEU), the state’s main discretionary reserve; and $900 million in the Safety Net Reserve.

Proposition 98 Reserve Reaches $9.5 Billion. In addition, the Proposition 98 Reserve, which is dedicated to school and community college spending, would reach $9.5 billion under the Governor’s May Revision. We do not include this reserve in general purpose reserves because withdrawals supplement the constitutional minimum spending level for K‑14 education and therefore do not help the state address future budget problems. However, this reserve does benefit schools because it mitigates the funding reductions that occur when the constitutional minimum drops.

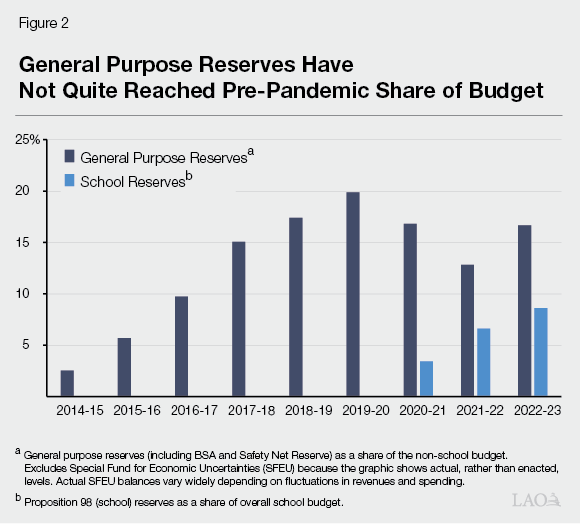

Under Governor’s Proposals, General Purpose Reserves Remain Below Pre‑Pandemic Levels as a Share of Budget. As Figure 2 shows, the state’s general‑purpose reserves increased steadily after 2014‑15, when Proposition 2 was passed by voters. In 2019‑20, the state made its first withdrawal from the BSA under the rules of Proposition 2 and the balance declined substantially. Since 2019‑20, reserves have grown in dollar terms as the state has continued to make new deposits into the BSA as required by the Constitution. Nonetheless, under the Governor’s May Revision, general purpose reserves as a share of nonschool spending would reach 17 percent by the end of 2022‑23, still below the pre‑pandemic share of 20 percent. In contrast, the Proposition 98 Reserve has increased from zero in 2019‑20 to $9.5 billion—or nearly 9 percent of school and community college funding—under the Governor’s May Revision estimates for 2022‑23.

The Surplus

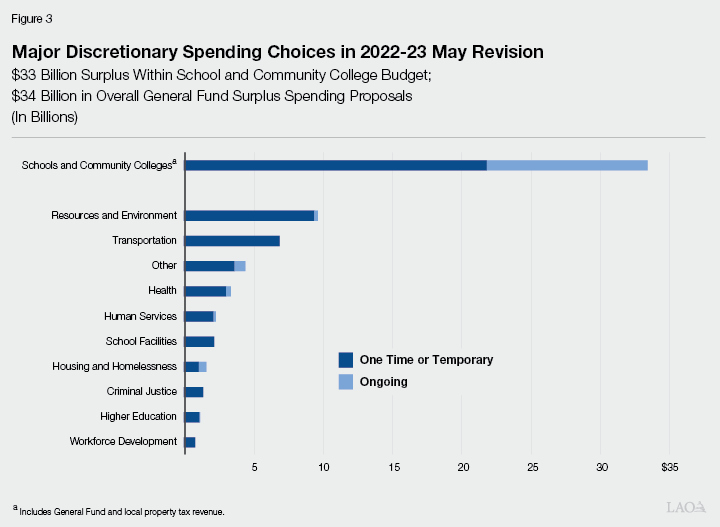

Figure 3 displays the major spending decisions that the Governor made in allocating state discretionary funds (including proposals carried forward from January). It includes: (1) the $34 billion in spending choices using the overall General Fund surplus (this figure excludes reserve deposits, tax refunds, and debt payments, which are shown instead in Figure 4) and (2) the $33 billion surplus within the school and community college budget. As the figure shows, schools and community colleges would receive the largest spending allocations reflecting the significant growth in Proposition 98. The remainder of this section discusses the major components of each of these funding amounts.

Overall General Fund Surplus

While the Governor’s May Revision provides a starting point for legislative deliberation, the Legislature ultimately will craft the final budget package for the 2022‑23 fiscal year. In that process, the Legislature will make its own determination about how to allocate funds available. One of the goals of this brief is to help the Legislature determine how much capacity the budget has for new augmentations so that it has the most flexibility to exercise its discretion. To achieve this, we estimate the available General Fund surplus: the amount of revenue available for new spending commitments after paying for the costs of programs under current law. (If, instead, we found spending under current law was higher than projected revenues, we would use the phrase “deficit” or “budget problem” to describe the difference.) This year, the concept of the surplus is more complicated because the state appropriations limit (SAL), under the rules of Proposition 4, constrains how the Legislature can allocate revenues that exceed a specific threshold. We describe the limitations the SAL places on how the Legislature can allocate the surplus in the next section.

We Estimate the Governor Allocated an Overall General Fund Surplus of $52 Billion in the May Revision. We estimate the Governor had a $52 billion surplus to allocate in the 2022‑23 May Revision, an increase of $23 billion over the $29 billion surplus we estimated was available in January. The figure is very similar to the $49 billion discretionary General Fund surplus identified by the administration, although some of our offices’ specific assumptions are different. (In the coming days, we will publish tables enumerating the specific proposals in the May Revision by program area.)

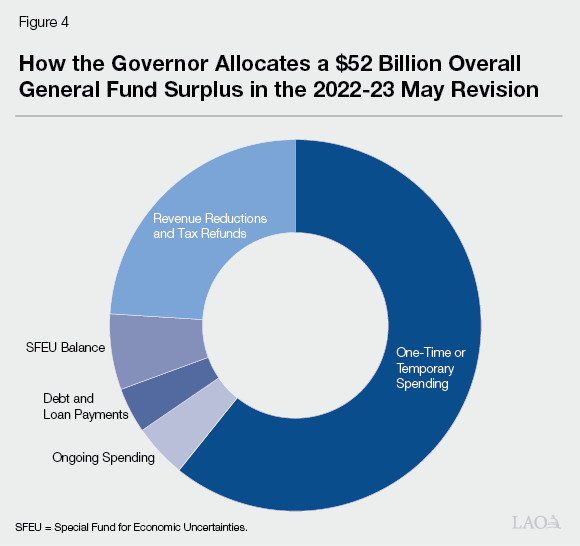

How the Governor Allocates the $52 Billion Overall General Fund Surplus. Figure 4 shows how the Governor proposes allocating the overall General Fund surplus. Overall, we estimate 95 percent are devoted to one‑time or temporary purposes and 5 percent are ongoing. Specifically, the Governor proposes allocating:

- $32 Billion to One‑Time or Temporary Spending on Programmatic Expansions. The Governor proposes spending about 60 percent of the overall General Fund surplus, or $32 billion, on a one‑time or temporary basis for a variety of programmatic expansions. (We define temporary to mean three years or fewer.)

- $12 Billion to Revenue Reductions and Tax Refunds. The Governor proposes using $12 billion, about 24 percent of the overall General Fund surplus, to reduce revenues. (Of this total, 97 percent would be one time or temporary.) In particular, this category includes the Governor’s $11.5 billion proposal to provide tax refunds to vehicle owners in California.

- $3 Billion to Reserves. The Governor proposes the Legislature enact a year‑end balance in the SFEU of $3.4 billion. The Legislature can choose to set the SFEU balance at any level above zero. However, recent budgets have enacted SFEU balances around $2 billion to $4 billion, which the state uses to cover costs for unanticipated expenditures.

- $2 Billion to Ongoing Spending Increases. The Governor’s spending proposals include $2.4 billion in ongoing spending, about 5 percent of the surplus. That said, under the administration’s estimates, the ongoing costs of the Governor’s budget proposals would grow significantly over time, totaling $7.4 billion by 2025‑26. The largest of these include $1.8 billion (in 2025‑26) for the proposed expansion of Medi‑Cal to all income‑eligible Californians and nearly $600 million for a State Supplementary Payment grant increase, according to administration estimates. (In the next week or so, we will issue our estimates of the cost of ongoing proposals.)

- $2 Billion to Pay Off Debts and Liabilities. Each year, the state pays many billions of dollars towards debts and liabilities. (Under the Governor’s May Revision, for example, the state would make $3.4 billion in constitutionally required debt payments under Proposition 2, as well as other routine debt payments made by the state, such as annual actuarially required contributions to the state’s pension systems, debt service on state bonds, and the state’s plan to prefund retiree health.) In addition to these routine payments, the Governor proposes the Legislature use $2 billion in overall General Fund surplus funds to repay state debts and liabilities. This includes $1.3 billion for converting some projects currently funded by lease revenue bonds to cash and repaying around $600 million in special fund loans to the General Fund.

Surplus Within School and Community College Budget

Total state spending on schools and community colleges is determined mainly by a set of constitutional formulas set forth in Proposition 98. These formulas establish a minimum funding requirement for K‑14 education, commonly known as the minimum guarantee. The state meets the guarantee through a combination of General Fund and local property tax revenue. The Legislature, in turn, decides how to allocate this funding among specific school and community college programs. Many factors affect the costs of these programs, including changes in student attendance and statutory cost‑of‑living adjustments (COLAs). When the guarantee exceeds the cost of existing programs, the difference is available for new commitments. For simplicity, we refer to this amount as the “surplus” within the school and community college budget. This amount is separate from the overall General Fund surplus and must be allocated for school and community college programs (or deposited into the Proposition 98 Reserve). Under the Constitution, the Legislature can appropriate more than this amount (by increasing funding above the minimum guarantee) or less (by suspending the guarantee with a two‑thirds vote of each house).

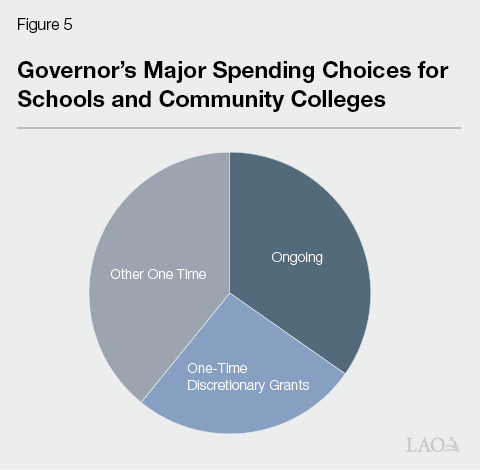

How the Governor Proposes Allocating the Surplus Within the K‑14 Education Budget. After setting aside funding for statutory COLAs and other planned program expansions, the Governor’s budget includes $33.5 billion in discretionary spending proposals to meet the minimum required funding level for schools and community colleges. As Figure 5 shows, the Governor proposes allocating $11.6 billion for ongoing program increases and $21.9 billion for one‑time purposes. The largest one‑time augmentation is for $8.75 billion in discretionary block grants—$8 billion for schools and $750 million for community colleges—that would be distributed on a per‑student basis.

The State Appropriations Limit

The SAL limits how the state can use revenues that exceed a certain limit. When revenues are expected to exceed the limit before the state makes its discretionary budget choices, it has a SAL requirement. (In other words, a SAL requirement is the amount of revenue the state is required to allocate in ways that meet its constitutional requirements under Proposition 4.) Specifically, SAL requirements can only be met with:

- Tax Reductions or Tax Refunds. The first way the Legislature can allocate revenues in order to comply with the SAL is to reduce proceeds of taxes, for example, by reducing tax rates, increasing tax credits, or returning funds to taxpayers through tax refunds.

- Excluded Spending. Second, the Legislature can spend more on excluded purposes. Categories of excluded spending include: subventions to local governments, debt service, federal and court mandates, capital outlay, and emergency spending. For some exclusions, like federal and court mandates, legislative decisions play a limited role in increasing or decreasing the excluded spending. But for other exclusions, like subventions to local governments and spending on capital outlay projects, the Legislature has much more discretion.

- Excess Revenues Split Between Tax Refunds and School Spending. Finally, the Legislature can follow the provisions of Section 2 of Article XIIIB of the Constitution. Specifically, if appropriations subject to the limit exceed the limit on net across two years, the state must allocate the excess equally between taxpayer refunds and additional education spending. The Constitution also allows the state two additional years to make these payments.

SAL Requirements Now Significantly Impact Budget Choices. In the past, our office generally did not issue reports on the administration’s approach to meeting SAL requirements because the limit did not impact budget choices. In the past few years, however, the SAL has become a major feature in budget architecture and places constraints on the use of surplus funds. The reason the SAL is now a major feature of the budget is due to revenue growth exceeding growth in the limit. We discuss this dynamic in our report, The State Appropriations Limit.

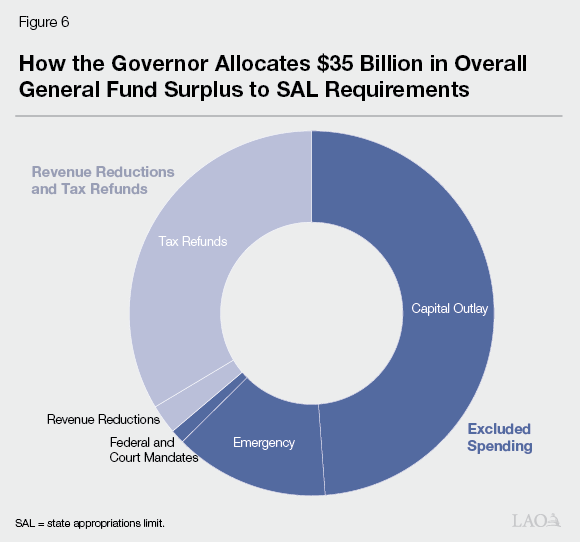

Governor Allocates $35 Billion in Overall Surplus to Address SAL Requirements. The Governor’s May Revision includes $35 billion in discretionary General Fund proposals that meet SAL requirements across 2021‑22 and 2022‑23. (This reflects 68 percent of the overall surplus.) Figure 6 shows the distribution of these proposals by type of SAL requirement. As the figure shows, about two‑thirds of the proposals are for excluded spending, including nearly half of the overall proposals going to capital outlay projects. (Importantly, the definition of capital outlay under the SAL is more expansive than the typical definition in the budget.) These capital outlay proposals include, for example, $2.2 billion for school facilities, $2 billion for the transportation infrastructure package, and nearly $2 billion for the strategic energy reliability reserve. About one‑third of the SAL‑related proposals are for revenue reductions and tax refunds, including the Governor’s $11.5 billion tax refund proposal for vehicle owners. (The nearby box also describes the Governor’s changes to the SAL calculation in the May Revision, which result in slightly lower SAL requirements across the budget window.)

Governor’s Proposed Administrative and Statutory Changes to the SAL Calculation

The Governor proposes two changes to the state appropriations limit (SAL) calculation, which both lower requirements across the budget window. Taken together, these changes result in lower SAL requirements by nearly $3 billion in 2022‑23. Specifically, the administration:

- Counts More School District Capital Outlay Exclusions. School districts, like local governments and the state, have their own appropriations limits. State law requires most school districts to set aside a portion of their general purpose funding for the ongoing and major maintenance of their facilities. Districts currently set aside approximately $2.2 billion per year related to this requirement. These funds meet the definition of capital outlay for SAL purposes, and so the administration’s SAL calculations propose school districts exclude this spending from their limits. Because of the way school district limits interact with the state’s limit, excluding this spending results in dollar‑for‑dollar reductions in appropriations subject to the limit at the state level.

- Counts Certain IT Project Costs as Excluded. The May Revision identifies information technology (IT) project costs totaling $227 million General Fund in 2021‑22 and $447 million General Fund in 2022‑23 as SAL excludable. The administration did not previously categorize these costs as excludable, but recently developed a methodology to exclude certain IT expenditures. Generally, the administration’s methodology considers development and implementation costs for approved IT projects to be SAL excludable, but does not exclude other costs to plan projects or maintain and operate IT systems from the limit.

We find the administration’s changes reasonable, but suggest the Legislature direct the administration to exclude additional IT expenditures, including costs for planning, maintaining, and operating certain systems.

Governor Also Allocates $5.1 Billion Within K‑14 Education Surplus for SAL‑Excluded Spending. In addition to the $35 billion in SAL exclusions that use the overall General Fund surplus, the Governor proposes using $5.1 billion from the surplus within the school and community college budget for SAL‑excluded purposes. The largest component is $3.2 billion for deferred maintenance ($1.7 billion for schools and $1.5 billion for community colleges).

May Revision SAL Estimates. Figure 7 shows the state’s final SAL position after accounting for all of the May Revision proposals. As the figure shows, 2020‑21 would end with “negative room” (appropriations subject to the limit above the limit) of $17 billion. However, 2021‑22 would have room of $19 billion. Because the state’s SAL position is considered on net over two fiscal years, these two years have roughly $2 billion in room remaining. However, at the same time, the Governor’s May Revision leaves $3.4 billion in unaddressed SAL requirements in 2022‑23.

Figure 7

SAL Estimates in the 2022‑23 May Revision

(In Billions)

|

2020‑21 |

2021‑22 |

2022‑23 |

|

|

SAL Revenues and Transfers |

$216 |

$256 |

$252 |

|

Exclusions |

‑83 |

‑150 |

‑113 |

|

Appropriations Subject to the Limit |

$133 |

$106 |

$139 |

|

Limit |

$116 |

$126 |

$136 |

|

Room/Negative Room |

‑17 |

19 |

‑3 |

|

Excess Revenues? |

No |

||

|

SAL = state appropriations limit. |

|||

Budget Structure Comments

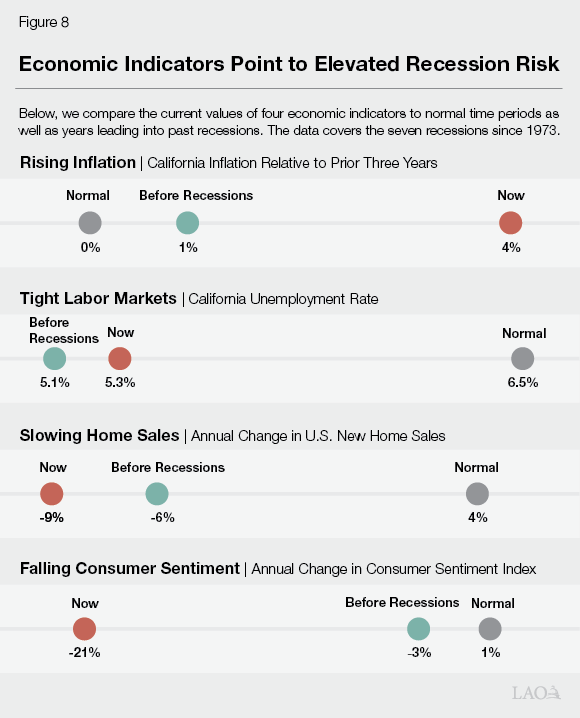

Recession Risk Heightened. Predicting precisely when the next recession will occur is not possible. However, certain economic indicators historically have offered warning signs that a recession is on the horizon. As shown in Figure 8, many of these indicators currently suggest a heightened risk of a recession within two years. High inflation and tight labor markets suggest an overheated economy is struggling to find avenues for further expansion, an observation seemingly supported by a decline in real gross domestic product in the first quarter of 2022. Home sales have declined as mortgage rates have risen rapidly. Consumer sentiment has fallen to levels typically seen only during recessions. Changes in prices of certain U.S. treasury bonds suggest financial markets may be pessimistic about the economic outlook. In the last five decades, a similar collection of economic conditions has occurred six times. Each of those six times a recession has occurred within two years (and often sooner).

Economic Conditions Weigh on Revenue Outlook. Past experience does not guarantee that we are heading for a recession. In our assessment, however, the risk of a recession is high enough to warrant a downward adjustment to our revenue outlook. As a result, we forecast stagnant revenues in the out‑years. The administration, in contrast, anticipates somewhat more growth, resulting in their estimates exceeding ours by around $13 billion by 2025‑26. In the context of the uncertainty surrounding these out‑year estimates, however, a difference of $13 billion is still relatively minor. The key distinction between our office and the administration is how much each of us insures against the risk of a recession during the forecast period. Whereas we reflect an elevated risk of a recession, this is less true of the administration. As such, while we think the administration’s estimates generally are reasonable, they do carry a higher risk of the state facing a shortfall in the next few years. (We discuss these issues and our revenue estimates in our post,The 2022‑23 May Revision: May Revenue Outlook.)

May Revision Leaves $3.4 Billion in Unaddressed SAL Requirements… Under the Governor’s May Revision, the state would have $3.4 billion in unaddressed SAL requirements in 2022‑23. We strongly urge the Legislature against enacting a budget that leaves unaddressed SAL requirements. The Legislature either could allocate more resources to purposes that meet the SAL’s requirements or save funds to meet the requirement next year. The nearby box discusses an example of how the Legislature can avoid leaving a budget‑year SAL requirement unaddressed.

Example of How to Address the Remaining SAL Requirement

Within the Governor’s May Revision revenue estimates and the state appropriations limit (SAL) framework, the Legislature has some options for addressing the $3.4 billion unaddressed SAL requirement in 2022‑23. For example, the Legislature can:

- Spend More Proposition 98 (1988) General Fund on Excluded Capital Outlay. Spending more Proposition 98 funding on capital outlay (or other excluded spending) would results in dollar‑for‑dollar reductions in appropriations subject to the limit at the state level because of the way school district limits interact with the state’s limit. For schools, the Legislature has several promising options. Most notably, it could allocate more funding for Transitional Kindergarten facilities to support the upcoming expansion of that program, increase funding for deferred maintenance beyond the amount included in the May Revision, or provide an infusion for the School Facility Program (either in addition to or in‑lieu of the amount from the overall General Fund surplus). Each of these options could support facility improvements that would benefit students and programs for many years. The Legislature could fund these options by reducing spending on the Governor’s proposed discretionary grants or other proposals it deems less essential.

- Swap Certain Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) and General Fund Expenditures. The administration’s 2022‑23 GGRF expenditure plan provides over $1.7 billion for projects that likely would qualify as capital outlay under the SAL, including high‑speed rail, transit projects, and incentives for heavy‑duty vehicles. (Cap‑and‑trade auction revenues that make up the GGRF are not counted as proceeds of taxes under the SAL.) The administration also proposes to use at least this amount of General Fund on climate‑related projects that are not SAL excludable. Should it wish to fund the same or a very similar mix of programs as the Governor, the Legislature could swap the fund sources for these climate‑related activities—use General Fund for the capital outlay projects and GGRF for the non‑excludable projects. This would reduce overall General Fund spending subject to the limit and help meet nearly $2 billion of the unaddressed requirement in 2022‑23.

- Reject Some Proposals That Do Not Meet SAL Requirements. Finally, the Legislature can reject some of the Governor’s proposals that do not meet a SAL requirement and instead spend those funds on SAL‑related requirements, as listed in this report under The State Appropriations Limit.

…And Sets Up a Fiscal Cliff as Early as 2023‑24. Although the unaddressed 2022‑23 SAL requirement is relatively small, because the SAL is calculated over two years, the 2022‑23 requirement must be considered alongside the state’s 2023‑24 SAL position. Our estimates suggest the May Revision sets the state up for a significant budget problem as soon as next year. Specifically, under our estimates of the Governor’s revenue assumptions and spending proposals, the state would face an additional SAL requirement of over $20 billion in 2023‑24, but have a surplus of only $1.6 billion in that year. This means that the state would have a budget problem of roughly $25 billion in next year’s budget process. Importantly, the state cannot “grow its way out” of this kind of budget problem. As we have discussed previously, for each $1 in revenues the state collects above the limit, it must allocate about $1.60 in constitutional requirements. This means that if revenues are higher than the Governor’s budget anticipates, the state will be in an even worse fiscal position. (For reference, see: The 2022‑23 Governor’s Budget: Initial Comments on the State Appropriations Limit Proposal.)

Recommend Increasing Reserves to Address Likely Fiscal Cliff. The vast majority of the Governor’s discretionary budget augmentations are one time or temporary. Maintaining a focus on limited‑term funding is essential to the budget’s ongoing health. However, this approach alone is unlikely to be sufficient to stave off future budget problems. That is because, as we have discussed here, the state faces dual risks to its bottom line condition. The risk of a recession is heightened, meaning revenue growth could be slower than the Governor anticipates, resulting in budgetary imbalance. But even if revenue growth continues as the administration expects, under our estimates, the state would face roughly $25 billion in SAL requirements next year that would result in a corresponding budget problem. This amount approaches the entire balance of the state’s general purpose reserves for 2022‑23. If revenues grow faster than that, the problem likely would be, counterintuitively, even worse. We will issue our multiyear assessment of the budget’s condition in the coming week or so, and that report will offer more insights into the ranges of possible budget outcomes the state faces in the near future. In the meantime, we strongly recommend the Legislature consider building more reserves than proposed by the Governor in the May Revision. Additional reserves can help the state either address future SAL requirements or a budget problem resulting from a recession.

Surplus Allocation Considerations

This brief focuses on our assessment of the Governor’s May Revision budget structure and provides our guidance to the Legislature on budget architecture. The remainder of the piece provides our guidance to the Legislature on allocating the surplus with a focus on legislative flexibility, effectiveness, and sustainability.

Address All SAL Requirements. In total, the administration allocates $40 billion on a discretionary basis to meeting SAL requirements, but leaves $3.5 billion in unaddressed requirements in 2022‑23. We recommend the Legislature address all SAL requirements. For example, it could make statutory changes to the SAL or allocate more of the surplus to SAL‑excluded purposes. If the latter, we recommend the Legislature allocate no less than $44 billion to meeting SAL requirements (using either the General Fund surplus and/or the surplus within the school and community college budget).

Determine Allocation Among Options for Meeting SAL Requirements. The administration allocates 56 percent of its SAL requirements to capital outlay, 29 percent to tax refunds and revenue reductions, and 12 percent to emergency spending. The Legislature can choose any allocation among: excluded spending (such as capital outlay, subventions to local governments, and emergency spending), tax refunds and revenue reductions, and excess revenue tax refunds and school payments. In crafting its budget, we recommend the Legislature consider how its policy goals could align with each of these categories of allowable uses.

Assess Best Use Within Each Category of Excluded Spending. The majority of the administration’s excluded spending proposals would be allocated to (1) tax refunds and (2) transportation, natural resources, and energy‑related capital outlay. While the Legislature has indicated interest in both of these areas, we recommend the Legislature consider whether the approaches offered by the administration would be effective. Do the proposals address a well‑defined problem with a policy strategy that has been evaluated and found to be effective? Did recent budgets make similar augmentations that may have helped address pressing needs? Do state and local entities have the capacity to spend the funds on effective projects and activities in a timely manner?

For example, how could tax refunds be structured to be most effective? With an expanding economy and extensive federal government intervention over the last two years, many Californians—although certainly not all—have seen their incomes, savings, and wealth rise. Unemployment rates have fallen rapidly and job openings outnumber available workers. In turn, rising incomes and wealth have come along with rising prices, which increase the hardships of those who have not benefited from the economic rebound. Under such conditions, immediate, broad‑based refunds may not be the best approach. Delaying payments of refunds for a period of time while setting aside funds to help support Californians should the current economic expansion begin to wane could provide more effective relief. If the Legislature wants to provide refunds now, they may be better targeted to those with the least resources or those most in need.

Similarly, the Legislature can think about modifying the Governor’s infrastructure proposals to focus on its highest priorities. Drought, energy reliability, and wildfire response are areas worthy of state attention. However, the Legislature will want to evaluate whether the Governor’s specific proposals are the most effective ways at addressing these challenges. For example, in constructing its own energy package, the Legislature might want to consider (1) how much funding to dedicate to address potential near‑term electricity shortages as compared to initiatives to build longer‑term reliability, (2) how to balance activities that rely on fossil fuels to address reliability concerns against those that better align with its climate and pollution goals, and (3) where state expenditures might maximize California’s eligibility and competitiveness for drawing down additional federal funds.

The Legislature also could assess whether the administration’s hospital and nursing facility retention payments proposal would be likely to address attrition. Our understanding of the proposal is that payments would be conditioned on prior employment, rather than continued employment in the future. Therefore, whether these payments would be an effective retention strategy is unclear. Alternative approaches could be warranted to reduce staffing turnover.

Evaluate Whether Disbursing Funding Over Multiple Years Would Be Preferable to All at Once. Under the rules of the SAL, the Legislature could appropriate funds this year to a specific excluded purpose and disperse those funds over multiple years. The advantage of this approach is that it could allow the Legislature to allocate a significant amount of resources to a particular need (or set of needs) now, but would allow the benefits of that appropriation to be spread over many years. Moreover, with mounting signs that the economy is approaching the peak of its current expansionary cycle, delaying the infusion of these fiscal resources to when conditions most likely have softened could enhance the economic benefit of this policy. This also could help address administrative capacity challenges associated with large, one‑time allocations.

Identify Any Missed Opportunities. The May Revision proposes a number of new initiatives. While these may be meritorious, we recommend the Legislature consider whether there are (1) existing programs addressing problems that should be considered as a higher priority or (2) other issues that should be addressed more immediately. For instance, the May Revision proposes establishing new centers at the universities, but provides no augmentation for addressing the universities’ deferred maintenance. Similarly, the administration proposes new housing programs that likely could be folded into existing programs like Homekey. Doing so could make existing programs more flexible while also reducing the need for additional administrative capacity. The administration also proposes shifting funding from the Department of Public Health to the Office of Planning and Research for pandemic‑related communications. Shifting this responsibility—while the pandemic remains ongoing—could delay the dissemination of important information on vaccines and other public health measures. Moreover, this shift could result in duplication and mixed messaging. Avoiding these outcomes has been one of the lessons learned during the pandemic. Lastly, beyond the constitutional requirements of Proposition 2, the administration includes very few proposals to help the state prepare for the next downturn now. (Most of the administration’s proposals to increase reserves and pay down debt are scored in the out‑years. That is, after 2022‑23.)

Weigh Trade‑Off Between Reserves and Non‑Excluded Spending. Our analysis suggests state government cannot expand on an ongoing basis without risking significant budget problems in just a few years. Specifically, under our assessment of the Governor’s May Revision, the state would face a roughly $25 billion budget problem next year. Setting aside additional reserves now would help mitigate that problem. In the event of a downturn, our scenario analysis has indicated that substantially larger problems are plausible. Therefore, the Legislature must weigh how much of the surplus should be dedicated to reserves versus other purposes. The Legislature also could evaluate whether there are existing program expenditures to suspend in order to dedicate additional funds to reserves or new augmentations. We recommend taking a fiscally prudent approach, which would be to identify several billion dollars in non‑excluded spending and instead dedicate those funds to reserves.